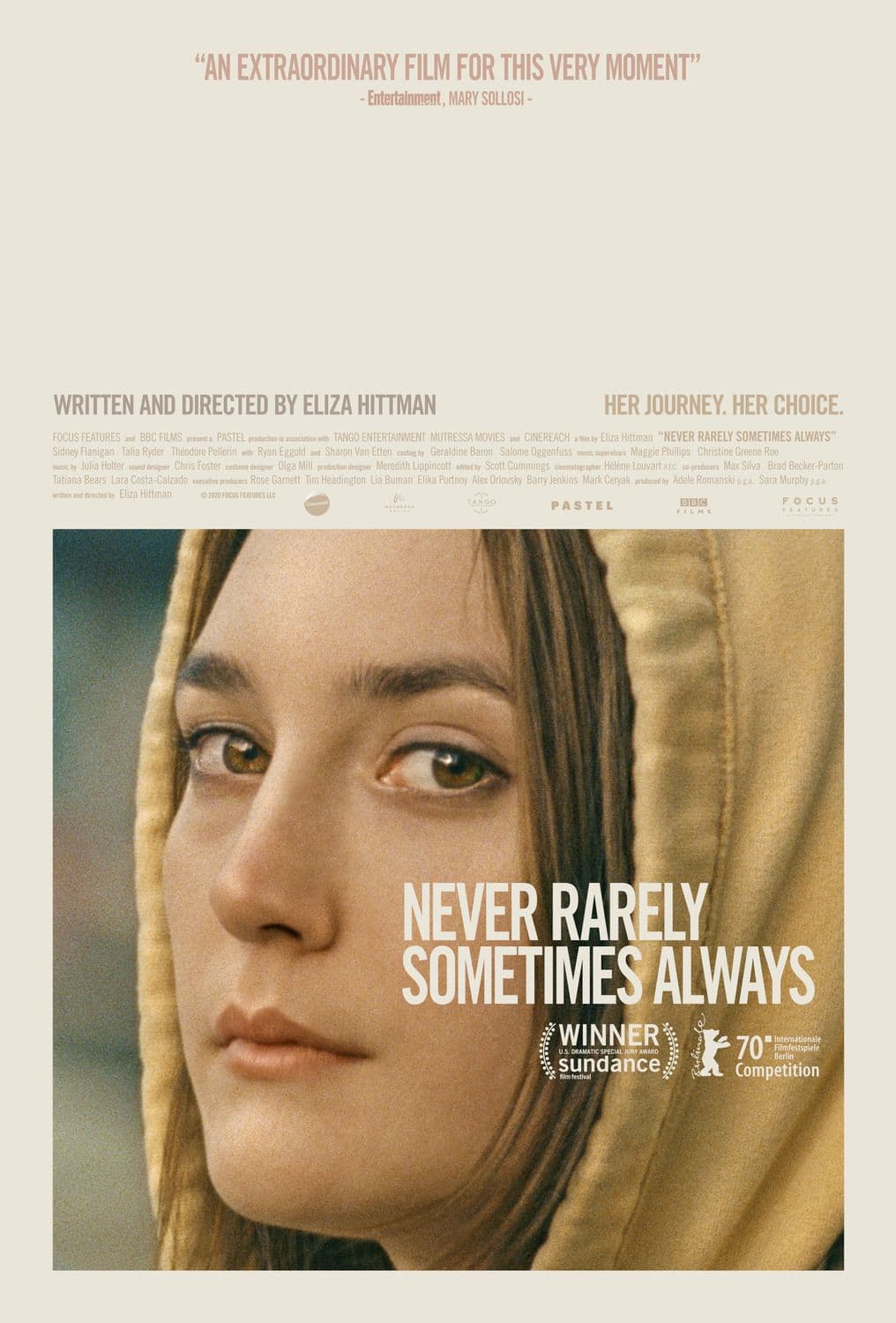

Never Rarely Sometimes Always

2020

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

In an age of shrill narratives and manifesto-cinema that parades its arguments, Eliza Hittman's Never Rarely Sometimes Always (2020) asserts itself with the subversive power of silence. It is a work of almost documentary rigor, a neorealism of the soul that follows its protagonist not to judge her or use her as a spokesperson, but simply to stand by her, recording every obstacle, every humiliation, and every imperceptible gesture of solidarity. The result is a devastating film, a punch to the gut delivered with the delicacy of a caress, which proves to be one of the most powerful and incisive indictments against the systemic hypocrisy that governs women's bodies. The film immerses us in a rural, post-industrial Pennsylvania, a landscape of the soul even before it is geographical. A kind of Limbo that becomes the periphery of existence in the film, a suspended condition where the protagonist struggles and desperately seeks a way out. It is the banlieue of American society, a place of low horizons and scarce opportunities, where the future seems a faded version of the present. Here lives Autumn (an extraordinary and laconic Sidney Flanigan), a teenager who discovers an unwanted pregnancy.

Hittman is truly masterful in delineating an environment of casual and pervasive male oppression. There are no explicit villains, but a constant and subtle oppression: the peer who humiliates her during a singing performance, the supermarket manager where she works who kisses her hands with slimy familiarity, an apathetic father, and a male figure responsible for her condition who remains a ghost evoked only by the pain in her eyes. In this context, her pregnancy is not an accident, but the almost mathematical consequence of an environment that offers neither protection nor escape. The only lifeline is her cousin and colleague Skylar (Talia Ryder). Their solidarity is the film's beating heart: a bond made of glances, of minimal gestures (the theft of money for the trip, hand clasped in hand during the toughest moments), a silent alliance against a hostile world.

Autumn and Skylar's journey from a small Pennsylvania town to New York City is not just a physical journey, but an odyssey through a geography of hostility, an obstacle course designed to discourage, humiliate, and punish. The film surgically exposes the social implications for a young woman trying to exercise her right. The first wall she encounters is that of institutionalized misinformation. She goes to a "Crisis Pregnancy Center," a pro-life center disguised as a clinic, where she is deceived with anti-abortion propaganda, a pregnancy test, and an ultrasound used as an emotional weapon. It is the first stop in a system that does not want to help her, but to re-educate her. Faced with Pennsylvania laws requiring parental consent, the only option is to flee to New York. Here, the medical bureaucracy, though professional and non-judgmental, reveals itself to be another form of labyrinth: the costs, the waiting times, the discovery of being further along in her pregnancy than expected, the need for a more complex procedure.

The scene that gives the film its title is a masterpiece of cinema and empathy. A Planned Parenthood social worker subjects Autumn to a questionnaire about her personal and sexual life. The camera remains fixed on her face for interminable minutes, while her answers ("never," "rarely," "sometimes," "always") reveal an abyss of endured traumas without anything ever being made explicit. In that gaze, in those silent tears, lies all the violence of a world that has left her alone.

Never Rarely Sometimes Always documents the consequences of an ideology, almost never showing its proponents. To analyze the cinematographic representation of "overbearing thought" that seeks to deny rights in the name of a faith used as a shield for cynicism, we must look at other works that have explored its roots and manifestations. This thought is not exclusive to the Catholic faith, but to every patriarchal fundamentalism that sees the control of the female body as its assertion of power. Cinema has depicted it in different ways. Peter Mullan's The Magdalene Sisters (2002) and Alexander Payne's Citizen Ruth (1996) come to mind, both in their own ways, and with their respective linguistic canons, fierce indictments against the wall of social and religious oppression.

Hittman's work takes a different path, quieter but equally radical. It does not show us the preachers or the politicians. It shows us the receipt of their sermons and their laws: a heavy suitcase, a night in a subway station, the face of a girl who must answer "always" to the question of whether a partner ever forced her into a sexual encounter. Its strength lies in documenting life, not in shouting against ideology, making its criticism even more unchallengeable. It is a necessary film, a silent act of resistance that reminds us how, behind every abstract debate, there is always a body, a story, a life.

Genres

Gallery

Featured Videos

Memorable Scene

Comments

Loading comments...