No Country for Old Men

2007

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Directors

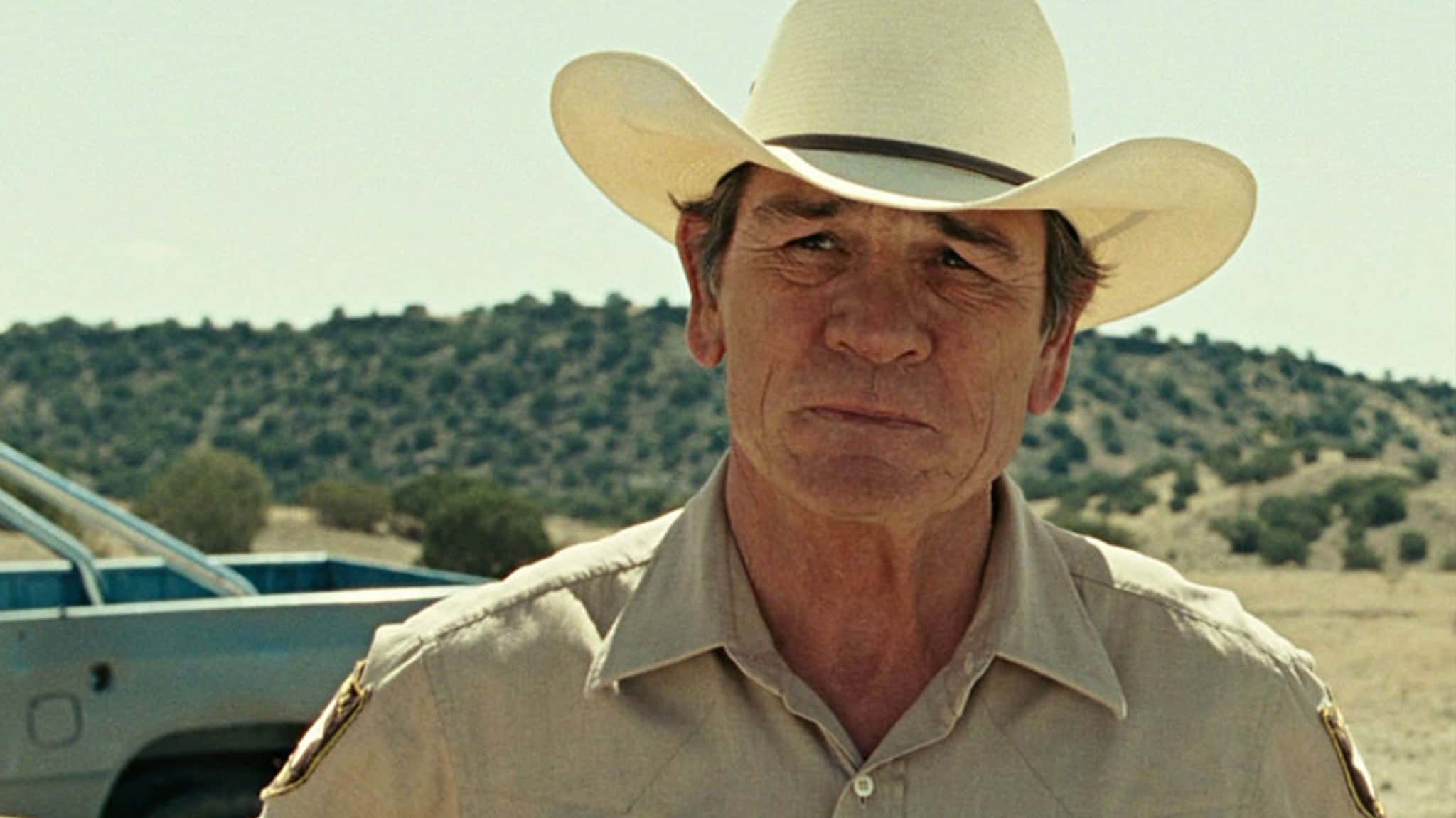

A warm voice, weathered by time, introduces the viewer to the film: it is an old provincial sheriff speaking, his words intrinsically linked to the places where he has always lived, tasting of dust and boundless distances. A man who has always fought to preserve the place he comes from, places in the deep American South forgotten by God and by men. His monologue is melancholic and looks back with nostalgia to the times when sheriffs didn't have to carry a gun to do their job. Then, with bitterness, he recalls a young man he had condemned to the electric chair, guilty of having killed a young girl.

Sheriff Bell bitterly concludes his reflections with a declaration of defeat: "The crime you see these days, it's hard to make sense of it. It's not that it frightens me; I've always known you have to be willing to die if you're going to do this job, but I'm not going to put my stake on the table... to go out and face something I don't understand. That would mean putting your soul at risk, saying, 'OK, I'm part of this world.'" It is a searing declaration of surrender, of dissonance with a world that now overwhelms all meaning, crushing the men who remain on its fringes. It is a lament not only for a bygone era of frontier justice but for the very erosion of comprehensible morality. Bell, embodied with a weary wisdom by Tommy Lee Jones, is more than a mere lawman; he is a reluctant oracle, bearing witness to the inexorable march of a new, formless evil that challenges old codes and the very logic of human interaction.

This is the scorching opening of the Coens' new and dazzling film. They have now become cult directors, revered as great masters of the camera and of human emotions transposed onto film. The Coen brothers, already architects of an unmistakable cinematic idiosyncrasy, here transcend their stylistic signature – a blend of black humor and meticulous plots – to deliver a modern American epic, a ruthless meditation on fate, chance, and the chilling banality of absolute evil. Their mastery manifests not only in impeccable narration but also in the radical use of sound and silence, a distinctive trademark that evokes atmospheres of palpable tension and metaphysical solitude, a true counterpoint to certain hyper-musical contemporary cinema.

The story is one of a bounty found by chance, amidst the aftermath of a gang shootout, following an attempted drug deal. The money is found by a local drifter, Llewelyn Moss, whose decision to take possession of that cash is not merely an act of greed but an unconscious defiance of fate. He defends his treasure to the death from an apocalyptic killer sent on the trail of the loot by the cartel that lost it, an ice-cold being who knows neither pity nor emotion. Also on the man's trail is Sheriff Bell, a cynical and disillusioned officer, whose objective is not to capture but to save the man who made the foolish mistake of taking the drug money. His is a moral rather than a legal crusade, a last attempt to assert a principle of order in a world sliding into chaos.

Special mention goes to Javier Bardem's performance as the killer, truly a testament to great acting mastery. Anton Chigurh, magnificently rendered by Javier Bardem in an Oscar-winning performance, is less a character and more a force of nature, an amoral algorithm of destruction. His weapon, a captive-bolt pistol, a tool for cattle slaughter, is employed with surgical precision against human beings, underscoring his detachment from conventional humanity. He is the terrifying embodiment of an arbitrary cosmos, a specter of violence whose motivations remain chillingly opaque, eluding any psychological profiling or moral categorization. He does not hate; he simply is. His presence evokes the existential dread of Camus or Beckett, the idea of a universe where purpose is absent and human endeavor is often futile.

Memorable in this regard is the scene featuring the killer and an elderly bazaar proprietor who unknowingly stakes his life on a coin toss. The dialogue between the two is something very close to being poised between avant-garde theater of the absurd and a blazing exchange of lines from a 1950s film noir: "— What's the most you ever lost on a coin toss? — Excuse me? — The most you ever lost on a coin toss. — I don't know... I couldn't say... — Call it. — Call it? — Yes. — For what? — Just call it. — Well, I should at least know what's at stake... — You have to call it. I can't call it for you, that wouldn't be fair. — But... I haven't staked anything. — Yes, you have. You've been staking it since you were born, you just didn't know it. Do you know what date is on this coin? 1958. It's traveled twenty-two years to get here. And now it's here, and it's either heads or tails. And you have to call it, choose." This sequence is the quintessence of the film and a distillation of the Coens' genius. The coin, which could be mistaken for a simple narrative device, becomes the film's supreme philosophical declaration: a brutal game of chance where life and death hinge on the flip of a coin, exposing the fragile precariousness of human existence. It is a moment of pure, distilled Absurdity, resonating with the philosophical anxieties explored in plays like Waiting for Godot or the literature of Dostoevsky, but rooted in the visceral horror of a gun pointed at one's head.

Bell represents an endangered species, a moral compass that has lost its north in a rapidly expanding desert of unreasonableness. Chigurh, by contrast, is the embodiment of this new wilderness, an entity that operates beyond the confines of empathy or human understanding. The film, rigorously adapted from Cormac McCarthy's bleak and poetic novel, transforms the arid landscape of West Texas into a philosophical battleground, where the very definitions of good and evil dissolve into an indistinct fog. And Llewelyn Moss, the archetypal common man, is trapped between these two poles, his fatal weakness being the belief that he can outwit a force beyond his comprehension. His journey, marked by increasingly desperate attempts to cling to a fortune that curses him, serves as a grim parable for the limits of human action in a world governed by chaos. He is the involuntary protagonist of a brutally modern Western, where the lines between hero and villain are blurred, and survival depends not on courage but on pure, arbitrary luck. The near-total absence of a traditional soundtrack, a bold choice by the Coens and cinematographer Roger Deakins, further amplifies the tension, forcing the viewer into an uncomfortably intimate communion with the unfolding terror. By denying the catharsis often provided by crescendoing music, the film exposes us to the raw reality of violence, a stylistic choice that echoes the relentless realism of certain Sam Peckinpah films, though with a more distilled and almost surgical precision. "No Country for Old Men" is not just an impeccable thriller; it is a work of art that interrogates the nature of evil in the 21st century and the unbearable weight of fate.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...