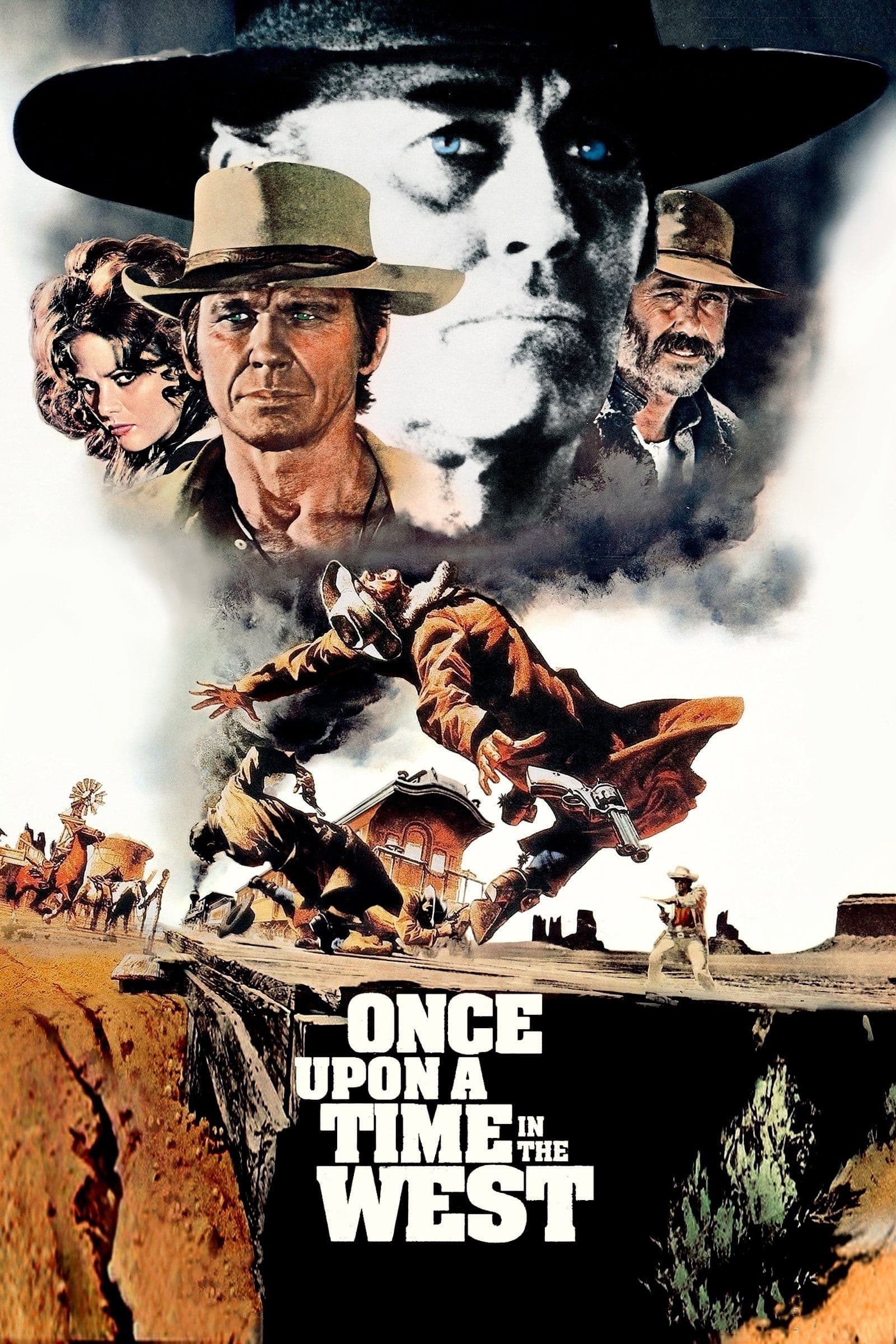

Once Upon a Time in the West

1968

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(2 votes)

Director

Leone abandons the cynical and bombastic tones of the Dollars Trilogy and, for his first Western film produced in the States, chooses a twilight and melancholic story, a true requiem for a genre and an era. With this masterpiece, he gives us, on the one hand, a taste of a frontier still wild and untamed, of humanity's challenge to nature and the unknown, but on the other, its inexorable decline in the face of the advancing Railroad, obviously understood as a metaphor for Progress, bringing modernity and the relentless Nemesis of the adventurous exploration of the first pioneers. It is not only the end of a historical era, but also the disintegration of an entire tapestry of myths and legends upon which the American epic was founded, reinterpreted through the disenchanted and tragic gaze of a European.

A work created with certainly more opulent means compared to the Dollars Trilogy, which lend it an epic scale and visual magnificence unprecedented in the genre, but which contains within itself an iconographic repository carved into the collective imagination, a true visual and sonic grammar that has influenced generations of directors. Undeniably, Ennio Morricone's soundtrack contributes decisively to this iconic status, a sonic architecture that transcends the mere function of accompaniment, becoming a character in itself. Each motif, inextricably linked to the protagonists, expresses their destinies, their memories, their vengeances, elevating individual sequences to moments of pure emotional catharsis. The lament of the harmonica, Jill's melancholic melody, Cheyenne's choral motifs, and Frank's relentless and metallic sound: these are all elements that merge with the images in a symphony of rare beauty and evocative power, carving into the viewer's memory not only what is seen, but what is felt.

The plot, though linear, is a mere pretext for exploring the human dramas unfolding in this transitional setting. A young woman, Jill McBain, travels from New Orleans to the far reaches of Utah to meet her new husband, a pioneer who had dreamed of building a family and a fortune on the soil of the West. Instead, she finds her new family brutally murdered and thus begins her journey, no longer one of hope, but in search of the murderers, accompanied by two emblematic figures of a dying world: an adventurer with the enigmatic face of Charles Bronson and a noble-hearted bandit, Cheyenne, portrayed by the extraordinary physicality of Jason Robards. Jill, splendidly embodied by Claudia Cardinale, emerges as a symbol of resilience and adaptation, the only figure capable of transitioning from the dust of the old West to the ambiguous promise of modernity, embodying the capacity of the "feminine" to build where the "masculine" tends to destroy or remain trapped in a cycle of violence.

Special mention, deserved and even understated, goes to Henry Fonda in the role of the villain, Frank. Leone's choice to entrust Fonda, an absolute icon of honesty and rectitude in American cinema, with the role of a ruthless child murderer was a stroke of genius. His blue eyes, so often associated with virtue, here become a mirror of glacial and inhuman wickedness, subverting decades of cinematic archetypes and creating one of the most memorable and disturbing characters in film history. In contrast, Charles Bronson as Harmonica, an old Western hero also seeking revenge, embodies the eloquent silence and iron determination of one who carries the weight of an indelible trauma, whose story is revealed in a chilling flashback, the true emotional core of the narrative.

So many scenes to mention, true masterpieces of direction and editing, most notably the opening scene (16 minutes) when three gunmen await the train at a ghost station, in a slow and idle chasing of time with an abundance of close-ups on feet, hands, legs, boots, hats and, above all, faces marked by dust and anticipation. It is a symphony of sonic details – the chirping of cicadas, the creaking of a wind pump, the insistent buzzing of a fly – that heighten the tension and sense of an almost metaphysical wait, culminating in the train's arrival as an epiphany of inevitable violence. This opening is not just a memorable sequence, but a declaration of Leone's intent: time is no longer marked by frantic action, but by waiting, contemplation, the characters' inner tension, an approach that redefined the very semantics of the Western genre.

A part of the criticism, such as that by Paolo Farinotti, initially failed to grasp its greatness and revolutionary nature, perhaps due to its unusual length, its extended pace, or its nature as a "Spaghetti Western" elevated to a work of art. It's a shame, because it was a pioneering and revolutionary film that profoundly introduced the concept of psychological depth into the Western genre, going far beyond the simple dichotomy between good and evil to explore the complex motivations, traumas, and inevitable downward spirals of an existence devoted to violence. Once Upon a Time in the West is not just a Western, but a funeral lament for the West itself, a twilight work that deconstructs its heroes and myths to reveal their raw, splendid, and tragic truth, leaving an indelible legacy in the history of cinema. It is a film that, in its painful farewell to a world that no longer exists, celebrates its memory with unparalleled lyrical and visual power.

Genres

Countries

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...