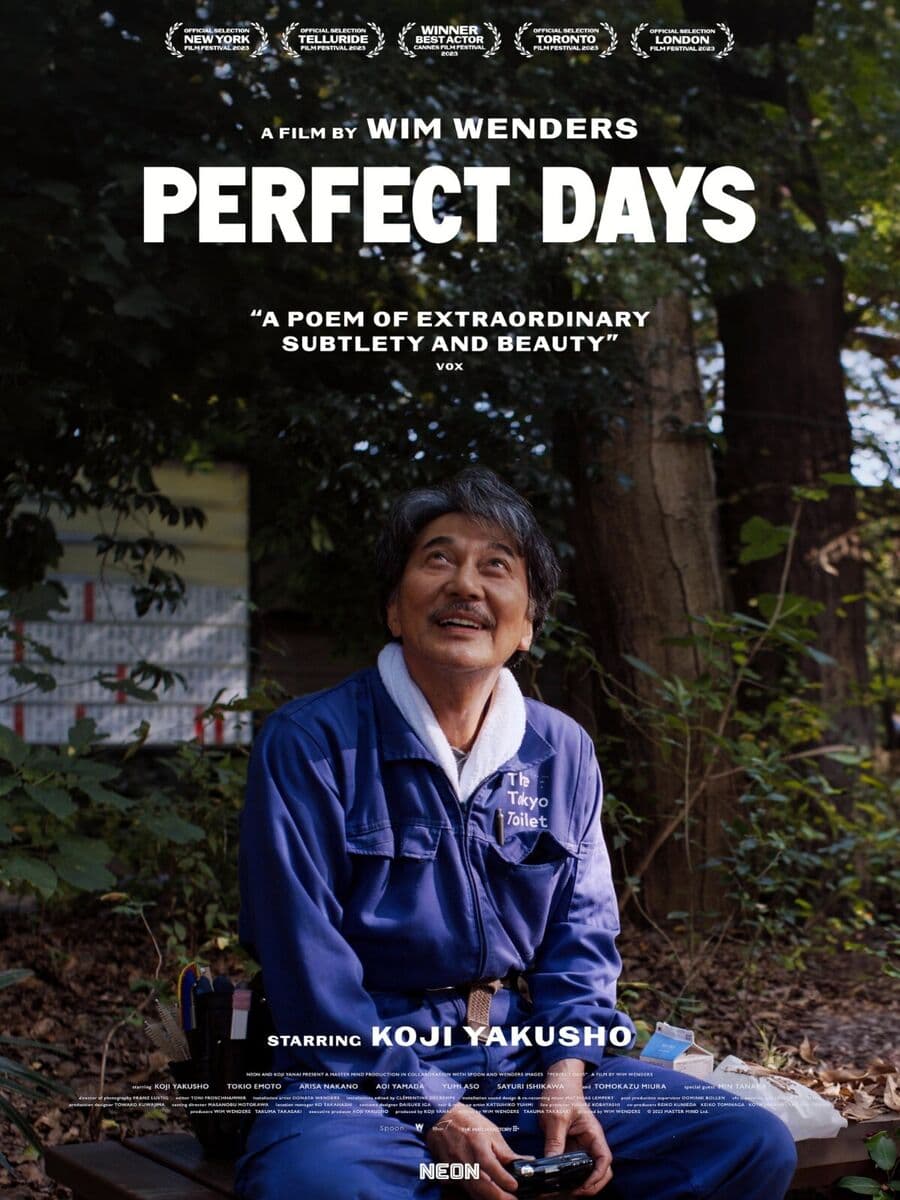

Perfect Days

2023

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(2 votes)

Director

The subdued mechanization of routine rises, before Wim Wenders' attentive eye, to a languid work of art caught in the act of becoming. In a cinematic era dominated by noise, haste, and screaming narrative complexity, Perfect Days presents itself as an act of quiet and radical resistance. It is an antidote, a balm for the hyper-stimulated soul. This film by the German director could be described as a placid glimpse into an ordinary life, gathering beneficial sensations that slowly but surely radiate throughout our being as we watch the film. The protagonist, Hirayama, is not a character in the classical sense of the word; he is a lay monk, a metropolitan anchorite whose monastery is a modest apartment in Tokyo and whose prayer is his impeccable daily routine.

Wenders' thesis, as simple as it is profound, is that happiness is not an event, but a process; it is not a destination, but a practice. The work of art that Hirayama builds day after day is not on canvas or film, but is his very existence. His routine is not a cage, but a ritual. Every gesture is performed with an almost Zen-like precision and mental presence: the way he folds his futon, waters his maple seedlings, chooses a cassette tape from his impeccable archive (Patti Smith, Lou Reed, The Kinks), looks up to photograph the komorebi with his old Olympus, that untranslatable and wonderful Japanese word that describes the sunlight dancing through the leaves of the trees. Komorebi is the central metaphor of the film: every day, the light creates unique and unrepeatable patterns, even if the tree is always the same. So is Hirayama's life: the structure is the same, but within it he is able to capture the unique unrepeatable nature of the moment, the ‘here and now’ in its purest form. His art is not creation, but attention. He reads Faulkner and Patricia Highsmith, listens to the music he loves, and takes care of a small public space. In an almost transcendentalist echo, his corner of Tokyo becomes the Walden Pond of a modern Thoreau, a place where life is deliberately reduced to the essentials in order to discover what really matters.

The poetics of humility, the metropolitan gaze towards a reality often hidden from us that conceals glimpses of pure elegy, is the key to this work. Wenders focuses his gaze on a protagonist and a profession that contemporary society relegates to the margins of invisibility: a public toilet cleaner. But here lies the stroke of genius, which stems from a fundamental production anecdote: the film was commissioned as part of “The Tokyo Toilet Project,” a real initiative involving world-renowned architects (such as Tadao Ando and Shigeru Ban) to redesign the public restrooms in the Shibuya district. Wenders takes this documentary inspiration and transforms it into poetry. The toilets in the film are not sordid places, but small, perfect pieces of architecture, almost temples of everyday life, sanctuaries of design and civilization. And Hirayama is not just a cleaner; he is a guardian, an officiant who takes care of these spaces with an almost priestly dignity and respect. His metropolitan gaze is not dazzled by the neon lights of Shinjuku, but lingers on parks, small second-hand bookshops, and underground restaurants. It is a Tokyo on a human scale, a city reinterpreted through a map of humble gestures and hidden beauty.

Wim Wenders' love for Japan, and in particular for the master Yasujirō Ozu, is the code that allows us to decipher the entire film. Already in 1985, with his documentary Tokyo-Ga, Wenders was searching for the spirit of Ozu in modern Tokyo. Perfect Days is the culmination of that search, a tribute so profound that it becomes an original work in its own right. The style is purely Ozuian: the camera is often static, positioned at tatami height, the conversations are elliptical, and the dramas (such as the arrival of the granddaughter Niko) are hinted at and resolved with modest grace, without any shouted catharsis. As in Ozu's films (think of Tokyo Story), dignity lies in the silent acceptance of the cycle of life, of small joys and inevitable melancholy. Here, Wenders accomplishes what we might call “inverted expressionism” or “expressionism of serenity.” Hirayama's soul, serene and at peace, has no need to distort the world. On the contrary, he expresses his inner harmony by aligning himself with the order, cleanliness, and geometry of the outside world. His peace is reflected in the transparency of a public bathroom designed by Shigeru Ban, in the orderly stack of his cassette tapes, in the simple rectangle of light that the sun casts on his wall. The expression of his soul is not in chaos, but in stillness.

The film ends with the face of Kōji Yakusho driving his van at dawn, listening to Nina Simone's “Feeling Good.” His face alternates between a smile, a tear, an expression of joy and one of deep sadness. In that mask of contrasting emotions lies the essence of a ‘perfect day’: not a day without pain, but a day when one has been able to embrace everything, beauty and its shadow. “Now is now, next time is next time,” says Hirayama. In this simple sentence lies a whole philosophy of life and the greatness of a film that, without raising its voice, teaches us to look at the world again.

Genres

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...