Little Big Man

1970

Rate this movie

Average: 3.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

One of the most atypical and fascinating Westerns ever made, it distinguishes itself with firm elegance from the genre's rigid and often monochromatic archetypes, ushering in an era of revisionism and introspection.

Arthur Penn takes a novel by Thomas Berger and crafts a work devoid of any moralism, interwoven with irony and spontaneous lyricism. This stylistic signature of his, already evident in masterpieces like Bonnie and Clyde, where violence was a brutal yet tragically human ballet, here culminates in a meandering epic that spans a century of American history with an apparent lightness that conceals a bitter depth.

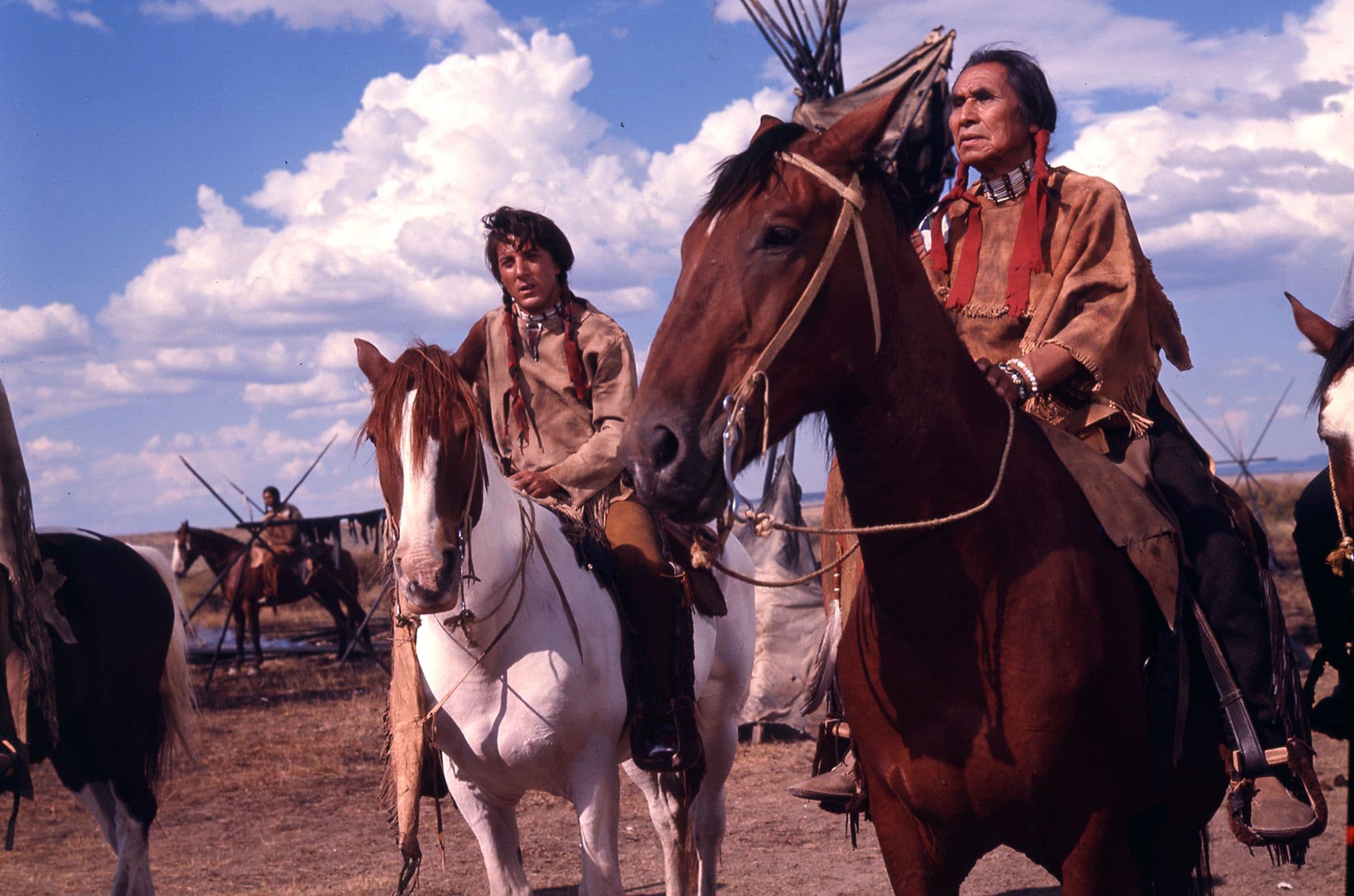

At 120 years old, Jack Crabb relives his life in a long flashback, a mosaic of fragmented yet vivid memories, making him a privileged witness and, at the same time, an unreliable yet fascinating narrator. Kidnapped by Native Americans at 10, he returned to the "civilized world" at 20. This existential oscillation between two diametrically opposed yet indissolubly linked cultures transforms his personal saga into an authentic examination of American identity at its most crucial crossroads.

His life is the life of the frontier lands, when the world of the whites and that of the Native Americans collided and at the same time interpenetrated, exchanging traditions and values. It is not merely a clash of civilizations, but a forced and often painful syncretism, where genocide lurked beneath the surface of daily interactions. Penn, with a sensibility that heralded the historiographical revisionism of the years to come, depicts Native Americans as the people who, more than any other, suffered humiliations and injustices, but does not issue sweeping judgments; instead, he offers an empathetic perspective, often comical in its absurdity, on the impending tragedy.

His narrative style always manages to be smooth and compelling, imbuing tragedy with comedy and violence with absurdity, an approach that clearly distinguishes it from John Ford's more traditional Westerns, where epic was often at the service of an uncritical foundational myth, or from Sam Peckinpah's raw revision, despite sharing his disillusionment with the frontier. His is an act of love towards a culture as free and light as the wind that swept the prairies, a hymn to human adaptability and ancestral wisdom, but also a most bitter commentary on the destruction of a world.

Released in 1970, the film fits perfectly into the climate of New Hollywood, a period of cinematic ferment in which American myths were deconstructed with fierce lucidity. Along with films like Soldier Blue (made in the same year), Little Big Man helped dismantle the stereotypical image of Native Americans, often reduced to savage barbarians or idealized noble figures, instead offering a more nuanced and complex portrait, albeit filtered through a picaresque lens. The Battle of Little Bighorn, for example, is not a triumph for Custer, but a tragic and bloody farce, an anticipation of the moral defeat awaiting America in Vietnam, a not-so-veiled parallel for the audience of the time, who were fully experiencing post-war disillusionment. The figure of General Custer, far from being a heroic facade, becomes a pompous and bloodthirsty caricature, a symbol of imperialist arrogance and destructive folly. This reversal of perspectives is not merely a stylistic choice, but a genuine historical hermeneutics, inviting the viewer to reconsider the entire palimpsest of Western narrative.

A masterful Dustin Hoffman in the role of Jack Crabb contrasts the character's candor with an ironic and almost mischievous undertone of a metropolitan creature, which only adds charm and credibility. His performance is a virtuoso display of metamorphosis, as Crabb is forced to be a thousand men in one: the adopted son of the Cheyenne, the elixir salesman, the gambler, the alcoholic, the hermit, right up to his encounters with the most famous outlaws of the West. Hoffman captures every nuance of this complex picaresque persona, making tangible the disorientation and resilience of someone who moves between worlds with antithetical moral and survival codes. He is the personification of an America unable to find its definitive identity, constantly oscillating between civilizing savagery and primitive purity, an outsider who, despite himself, becomes the privileged narrator of an epic saga. This act of love, therefore, is not blind or sentimental, but aware of the scars and losses, a requiem for a lost world and a warning for a future seemingly incapable of learning from past mistakes. Penn's mastery lies precisely in making this epochal drama intimate and universal, an odyssey of growth and disillusionment through the eyes of a man who, despite living a thousand lives, never truly felt part of any.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...