Platoon

1986

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

There are wars that cinema has depicted with epic distance, others with philosophical abstraction. And then there is the Vietnam War according to Oliver Stone. Platoon is not a film, it is an exorcism. It is the act of a veteran who, armed with a camera instead of an M16, returns to the hell of his youth to give it order, meaning, and form. The result is a work of almost unbearable visceral power, a film that smells of mud, sweat, and cordite, that grabs you by the throat and never lets go. It is not the most intellectual or poetic view of the tragedy of Vietnam, but it is, without a doubt, the most brutally, terribly honest.

To understand the greatness and uniqueness of this film, it is almost mandatory to place it in a sort of sacred triptych of war cinema, alongside its two spiritual brothers, equally monumental but profoundly different. If Coppola's Apocalypse Now is a metaphysical journey into Vietnam, a lyrical and hallucinatory work that uses war as a stage for an investigation into the heart of darkness of man, and Malick's The Thin Red Line is a transcendental poem, a pantheistic meditation on nature, grace, and violence, Platoon is the central panel, the realistic one. It is the story from below, the chronicle of a dirty war seen at eye level, from the point of view of the grunt, the infantryman in the jungle. Stone is not interested in myth or cosmology; he is interested in survival, fear, fatigue and, above all, the moral collapse that occurs when you are nineteen years old, handed a rifle and told that your life is worthless.

Oliver Stone's cinema, especially that of the 1980s, is the antithesis of subtlety. It is physical, aggressive, political cinema. His camera is a tool for total immersion. The director literally throws us into the thick of the action. His wide shots of the jungle, lush and menacing in their beauty, are constantly interrupted by fast, claustrophobic close-ups of the terrified faces of the soldiers. The handheld camera, feverish and unstable during the fighting, conveys panic and disorientation. Stone's aesthetic is that of a director who has left his mark because he had the courage to be direct, to get his hands dirty. His film was a necessary act of revisionism, an angry response to Reagan-era films such as Rambo 2, which had attempted to “re-win” the Vietnam War on screen, turning a national trauma into a muscular adventure. Stone grabsthat myth and literally tears it to pieces.

The story is one of a descent into hell and a painful moral education. The protagonist, Chris Taylor (an alter ego of Stone himself, played by a young Charlie Sheen), is a volunteer, a boy from a good family who dropped out of college on an idealistic impulse. Once in Vietnam, he discovers that the enemy is not only the invisible and lethal Viet Cong, but also the heat, the insects, the fatigue and, above all, the division that tears his own platoon apart. The genius of Stone's screenplay is that it structures the film like a modern medieval morality play, where good and evil face each other in the same uniform in a sort of Manichaeism. Chris's soul, and by extension that of America, is torn between two antithetical father figures: Sergeant Barnes (a scarred Tom Berenger who is a mask of pure nihilism) and Sergeant Elias (an almost Christ-like Willem Dafoe).

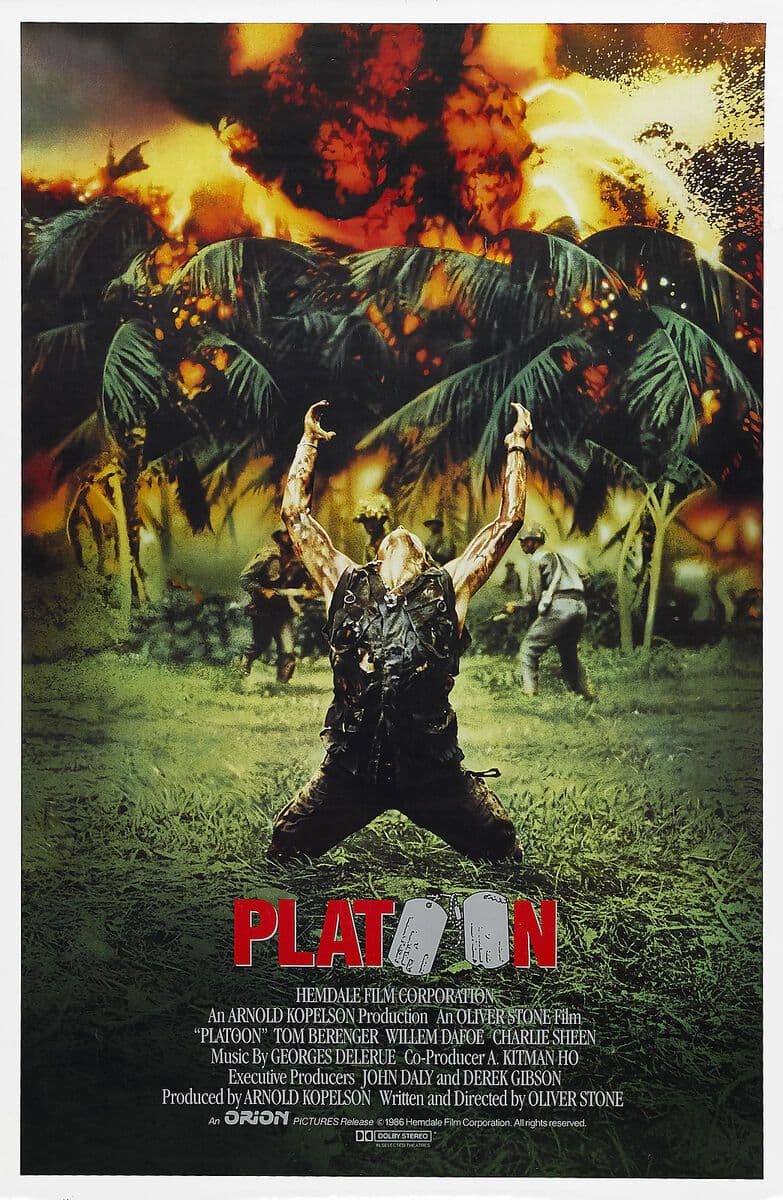

Barnes is war. He is the product of violence, a supreme soldier, efficient and ruthless, who believes that the only way to survive hell is to become the strongest devil. Elias, on the other hand, is humanity trying to resist hell. He is the soldier who has not lost his compassion, who still sees the people behind the uniforms and who opposes gratuitous brutality. The clash between the two, culminating in Barnes' cold-blooded murder of Elias during a fight, is the real heart of the film. And Sergeant Elias' martyrdom becomes an act of redemption for Vietnam. His death, with that iconic pose, arms raised to the sky as he is riddled with bullets, is a pietà of the jungle, a sacrifice that forces Chris to come out of his passivity and make a choice. To survive, not physically but morally, he must “kill” his bad father, Barnes, and embrace the legacy of his good father, Elias. Chris' famous final line, “We weren't fighting the enemy, we were fighting ourselves. And the enemy was inside us,” is the film's explicit thesis and its spiritual legacy.

This approach distinguishes Platoon from other great Vietnam stories. While Michael Cimino's The Deer Hunter explored the wound that war inflicted on the American working class and its idea of community, and Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket analyzed with almost scientific lucidity the process of dehumanization that creates a soldier, Platoon is the only one to focus so viscerally on the moral conflict within the platoon, on the battlefield. It is a film that offers no patriotic catharsis. Victory, if there is any, is only personal and bitter, that of having survived not only the bullets but also one's own dark side. For its brutal honesty, its emotional power, and for being the first true cinematic monument built from the perspective of those who actually fought that war, Platoon is therefore a seminal work, a cinematic experience that, once seen, is never forgotten.

Main Actors

Genres

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...