Ponyo

2008

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Hayao Miyazaki demonstrates once again, should there be any need, his immense artistic talent which translates into an enchanting poetic breath that he imbues in every drawing. This ability to infuse soul and life into every stroke, to make the paper pulsate with the energy of pure emotion, is a distinctive mark that elevates him beyond a mere animator, making him a true demiurge of the imagination. It is not just about masterful technique, but an aesthetic that pursues the truth of feeling, the resonance of myth, the delicacy of the everyday.

The Japanese Master combines this elegiac component with an incredible perception of the Fantastic, a visionary power that draws the most surreal creatures from Reality itself with truly disarming naturalness. In Ponyo, this alchemy reaches almost Zen heights, where the boundary between the real and the prodigious dissolves into a continuous flow, just like water, which is the primordial element of the film. It is not an ostentatious magic or a narrative device; it is the intrinsic magic of the world, if only one is willing to see it with eyes not yet tainted by adult, disenchanted rationality. It is the same wonder that pervades the encounter with the Totoros or Kiki's flight, a thin layer of enchantment that reveals the depth and hidden soul of nature and existence. The influence of Shintoism, which animates every natural element, is palpable, but transfigured into a universal and accessible vision.

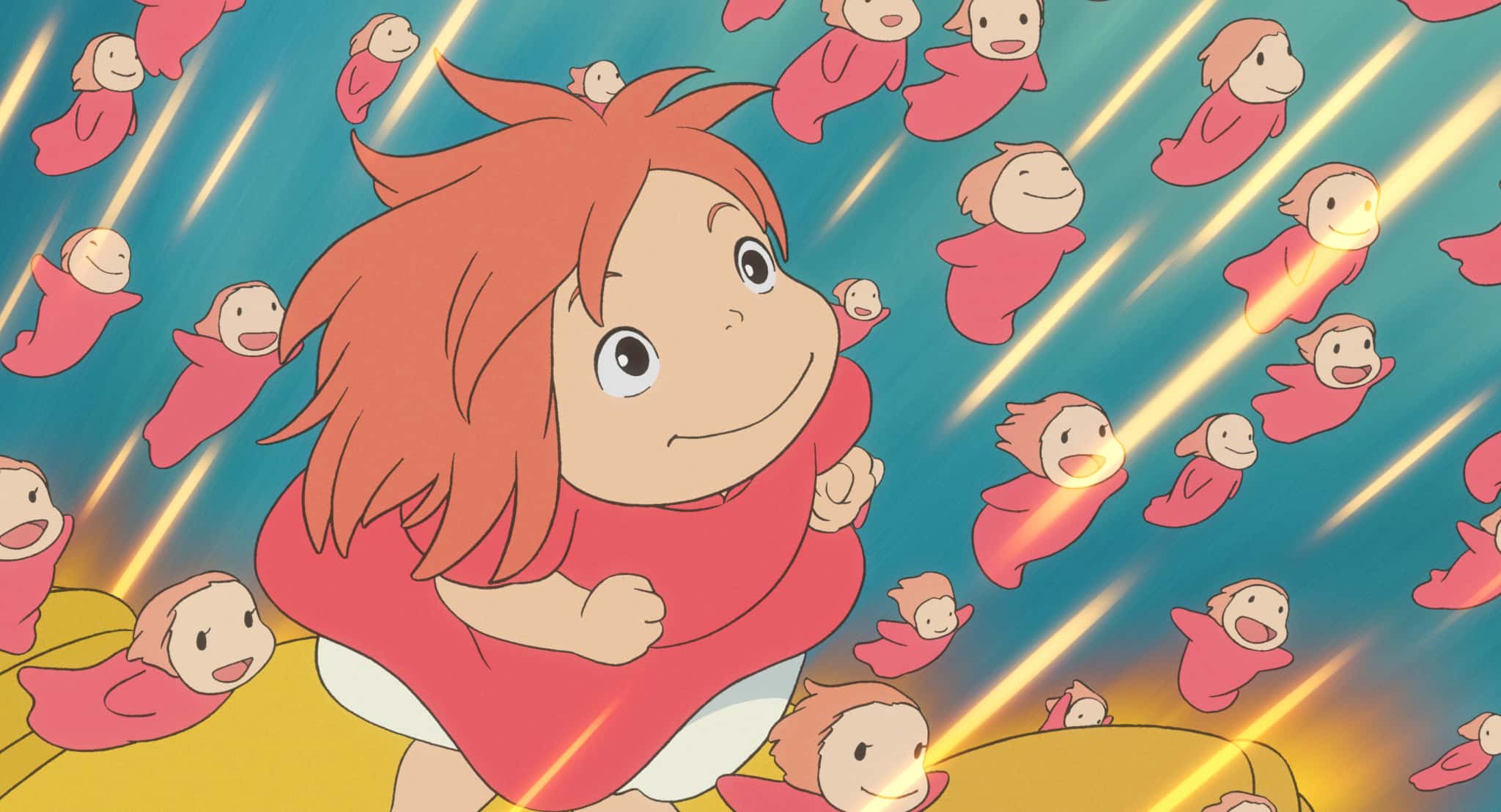

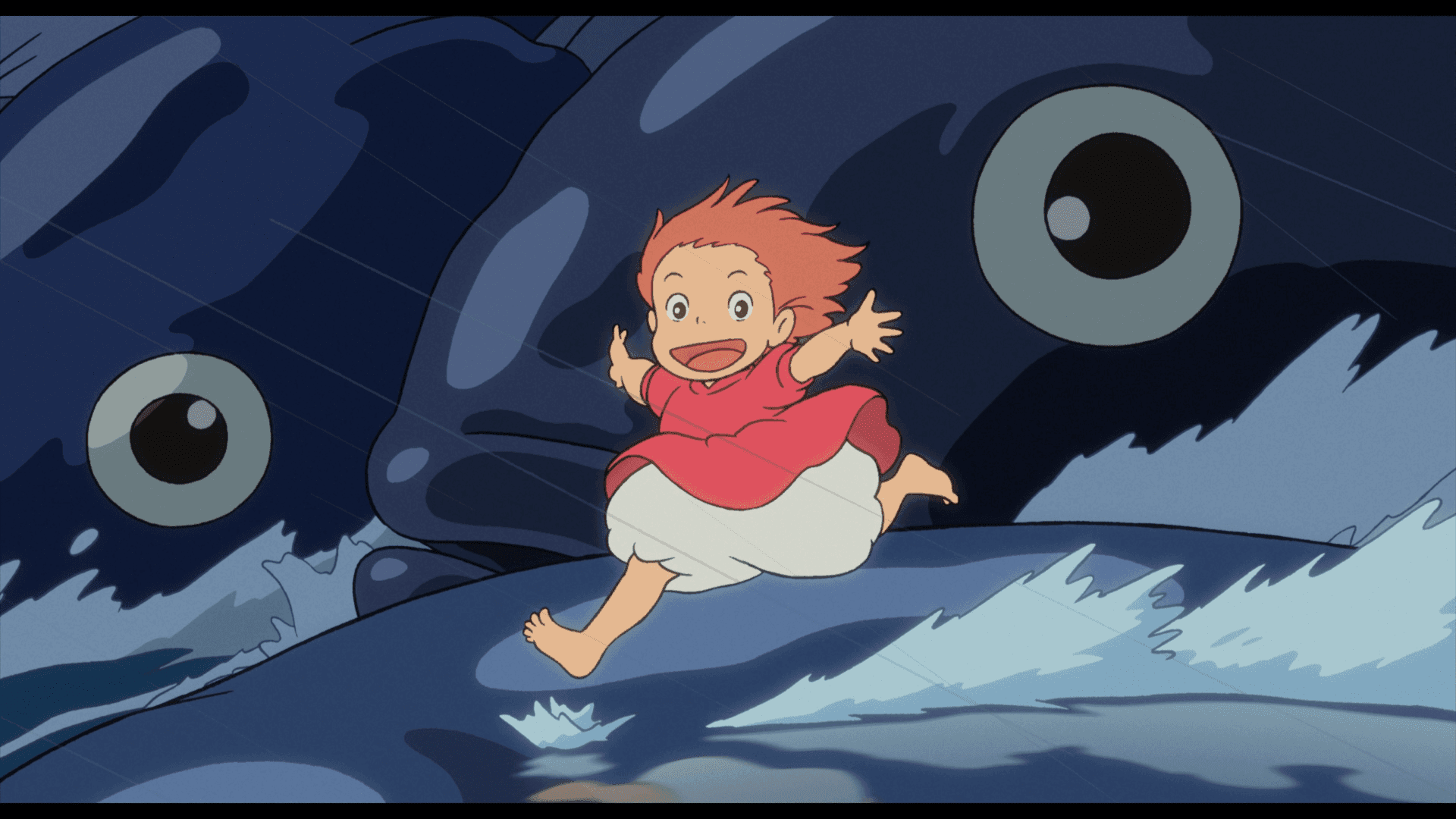

The intimate beauty of his works lies precisely in this delicate commingling of poetry and dream, both perfectly interwoven with the fabric of reality. Miyazaki does not merely paint fantastical worlds; he invites us to recognize them in our own. The choice to return to entirely hand-drawn animation for Ponyo, even in the fluid and complex movements of waves and marine creatures, is a statement of intent. It confers an organic, almost pictorial feeling to the film, reflecting the innocence and spontaneity of childhood, and translates into a fluidity that seems to mimic the very essence of water, never the same, always in flux.

Thus, when watching one of his films, one gets the impression of suspending the rational analysis of Reality and accepting, through a secret pact, every wonder and marvel that will spring from Miyazaki's pencil with enthusiastic adherence to his project. It is an almost regressive experience, in the noblest sense of the term: one is invited to shed intellectual armor, to forget the categories of possible and impossible, to embrace a dreamlike logic, where the logic of feelings and intuitive perception prevails over strict causality. The audience is called to become complicit, to reactivate that "childlike faith" that allowed one to believe in fairy tales and parallel worlds with the same conviction as one believes in the chair they are sitting on. This pact is not an act of naivety, but an awakening of sensitivity, a reminder that existence is inherently wonderful, if only one retains the capacity to be surprised by it.

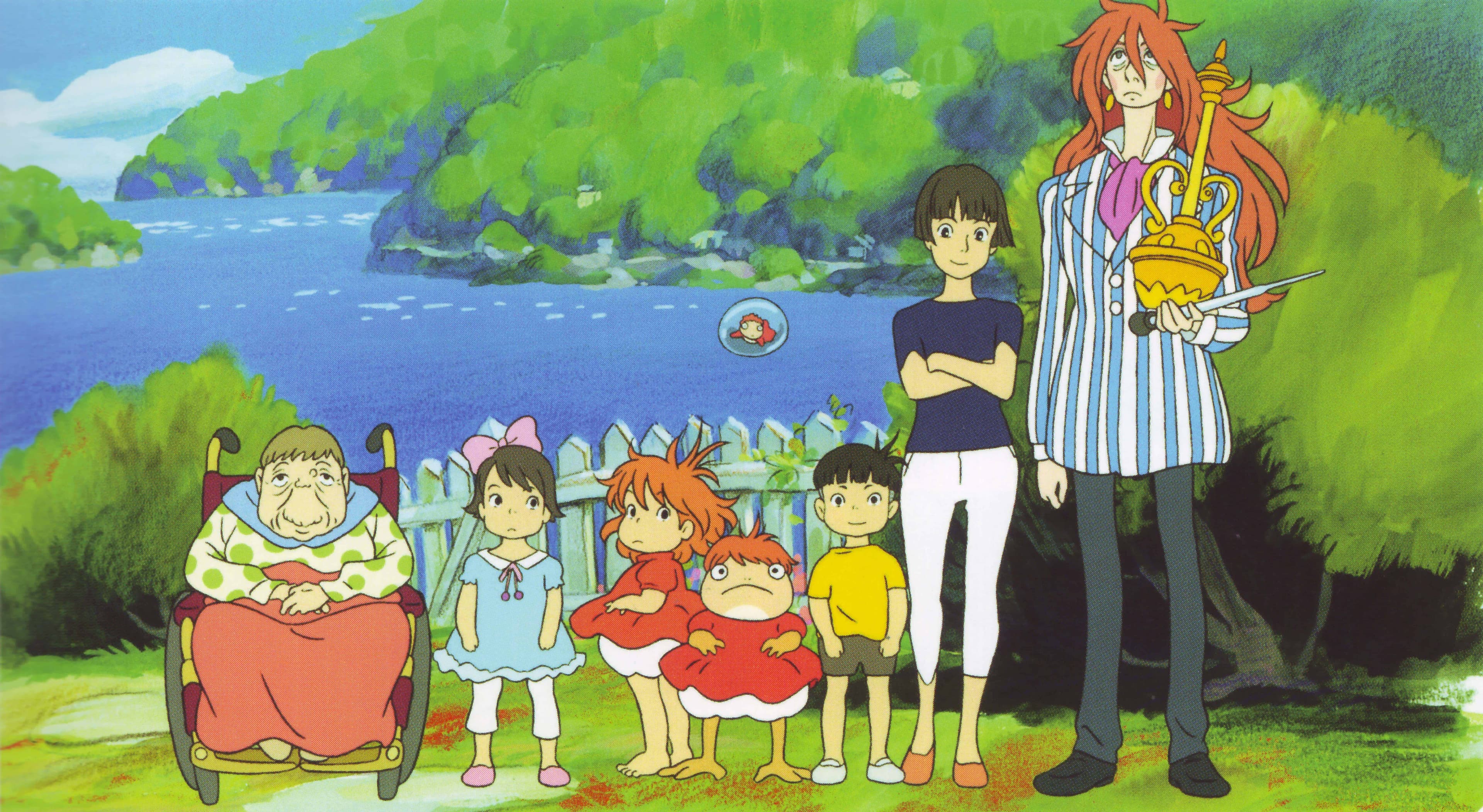

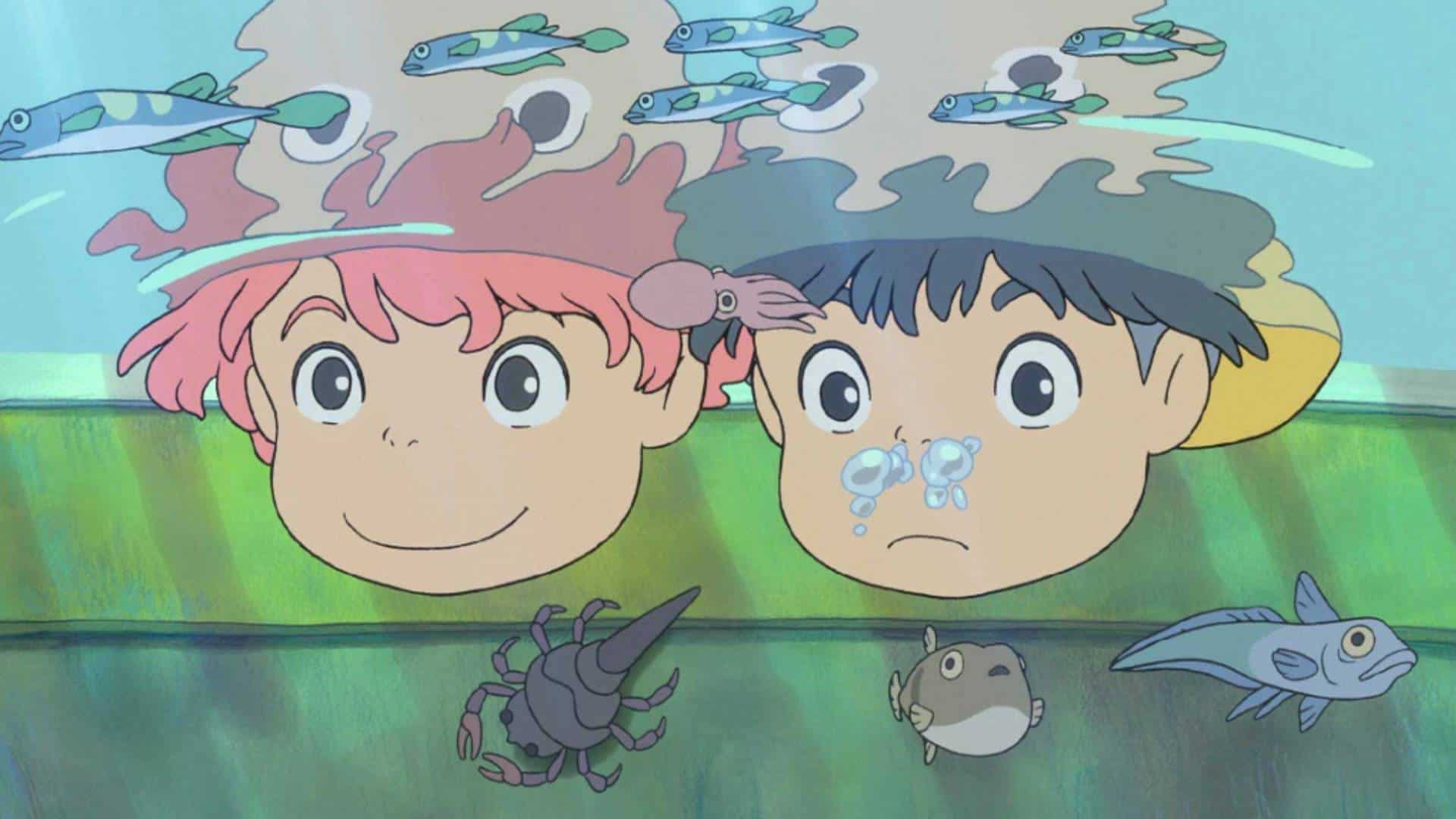

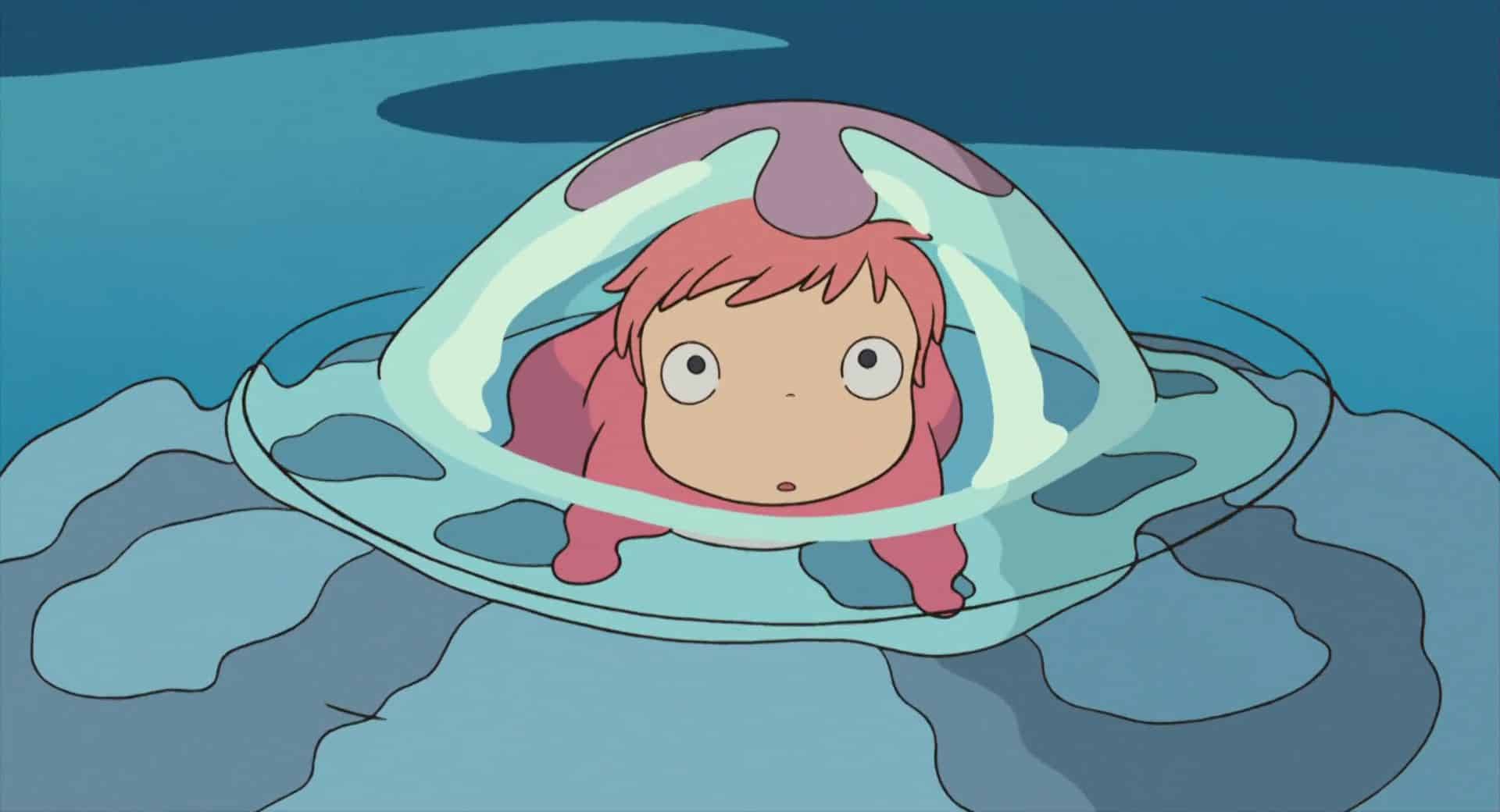

A small half-fish, half-human creature escapes the control of a sea wizard and remains trapped in a bottle on the seabed. This opening, which echoes Andersen's Little Mermaid but reworks it in an exquisitely Miyazakian key, immediately introduces the theme of freedom and discovery. Struggling to free herself from her glass prison, she manages to reach the shore where she is picked up by Sôsuke, a boy who was playing nearby. The encounter between the two is not by chance, but an alignment of purity and innocence that allows the fantastic to break through.

Breaking the bottle to free the small creature, Sôsuke cuts his finger and a drop of his blood lands in the little being's mouth. It will be the beginning of a transformation for Ponyo that will lead her to become a girl, endangering the fragile marine balance. Here Miyazaki touches upon a recurring theme in his poetics: the interconnection between man and nature, and the consequences – often disastrous – of human action on the environment. Ponyo's transformation is not just a physical metamorphosis, but a catalyst for natural events that recall the primordial and sometimes destructive force of the oceans, a subtle but powerful warning about the delicacy of our ecosystem.

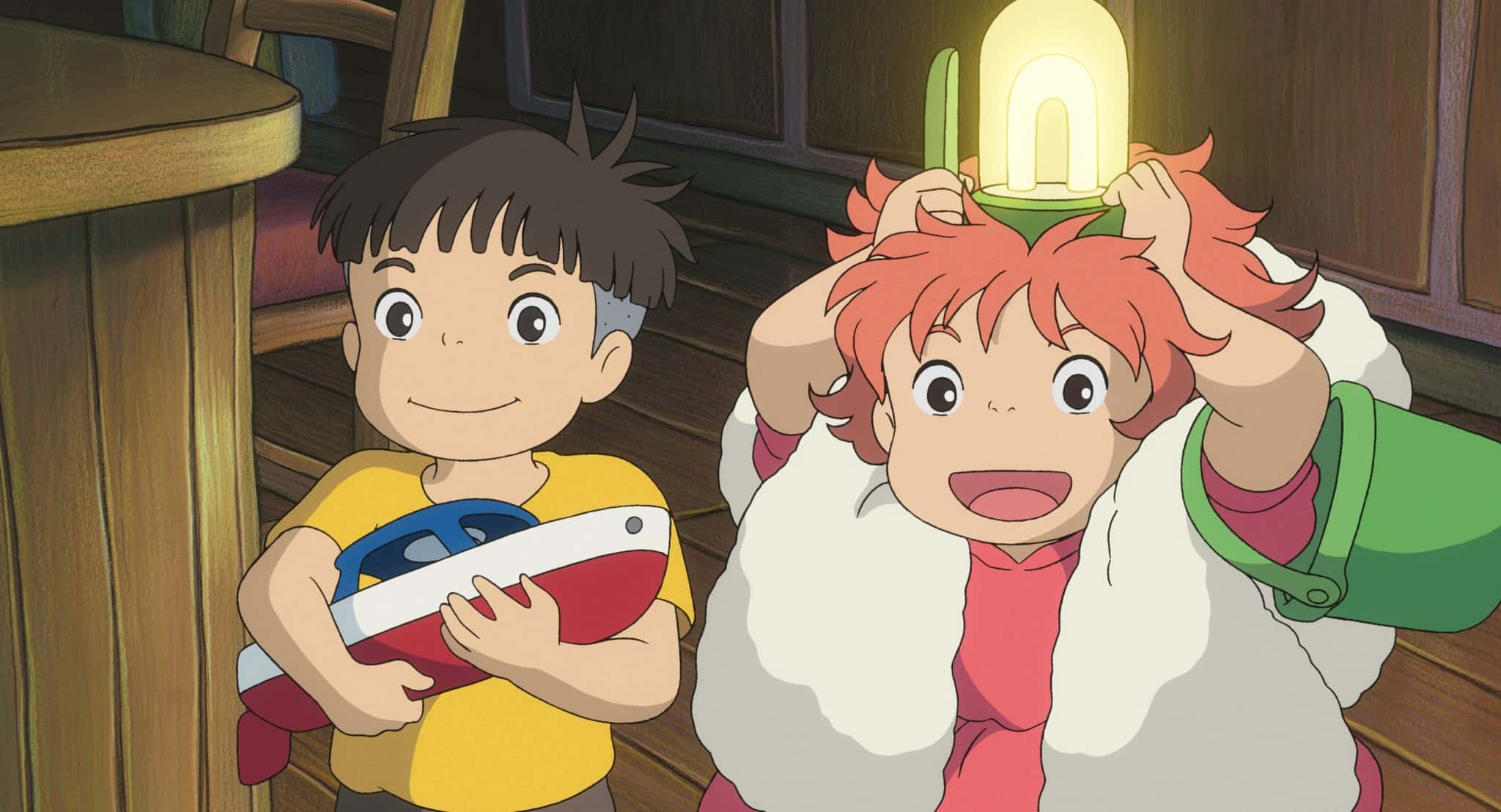

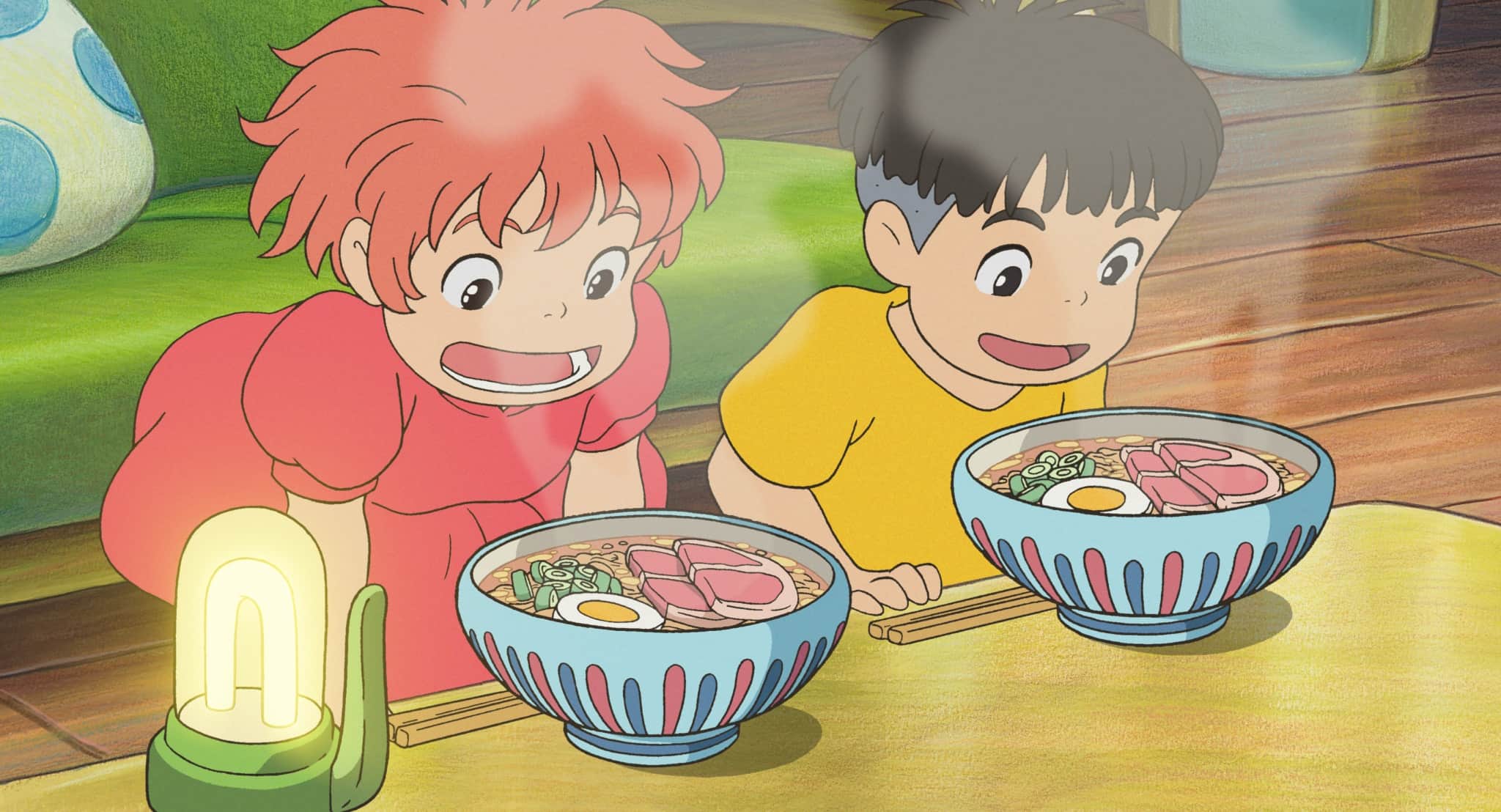

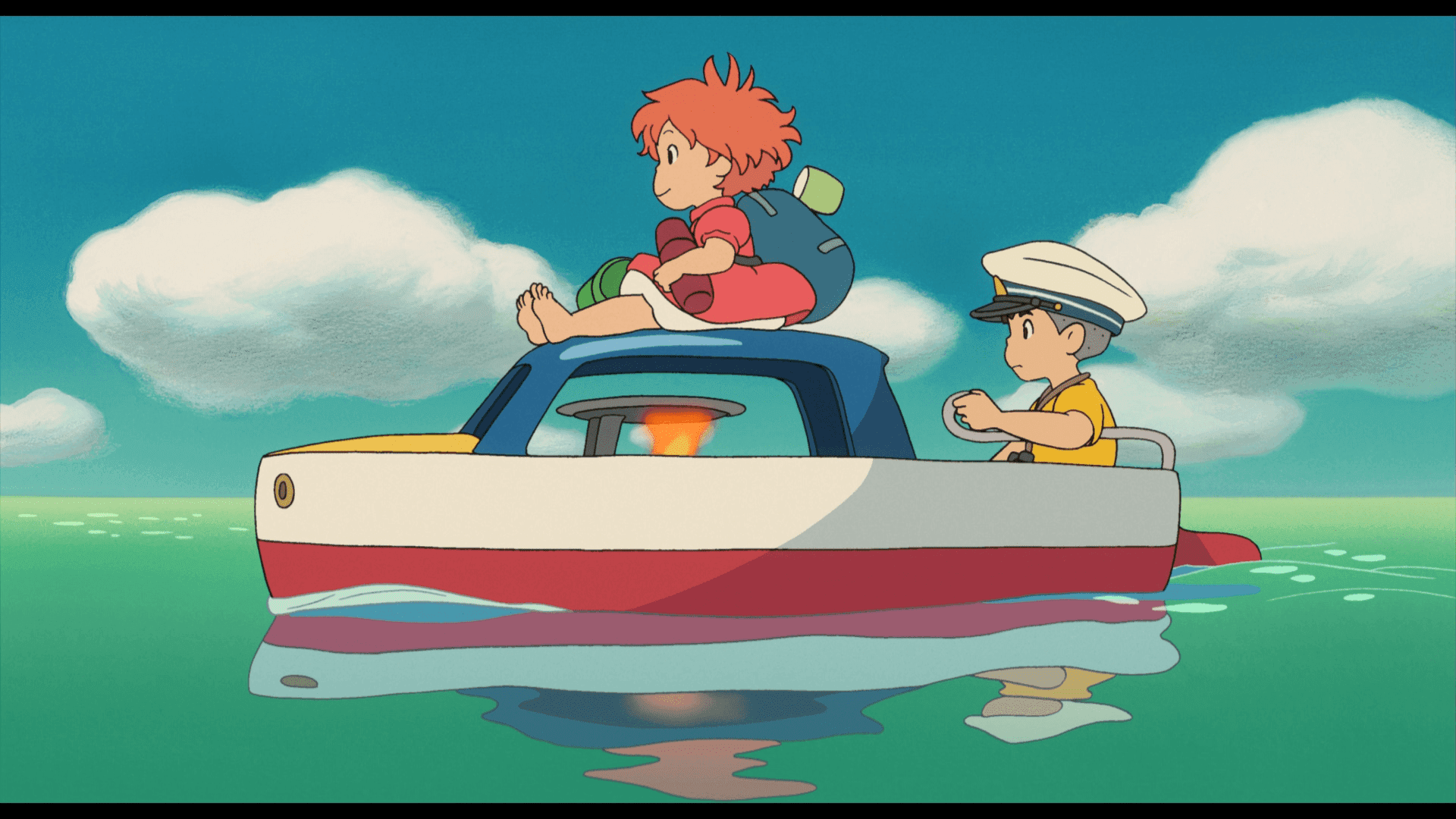

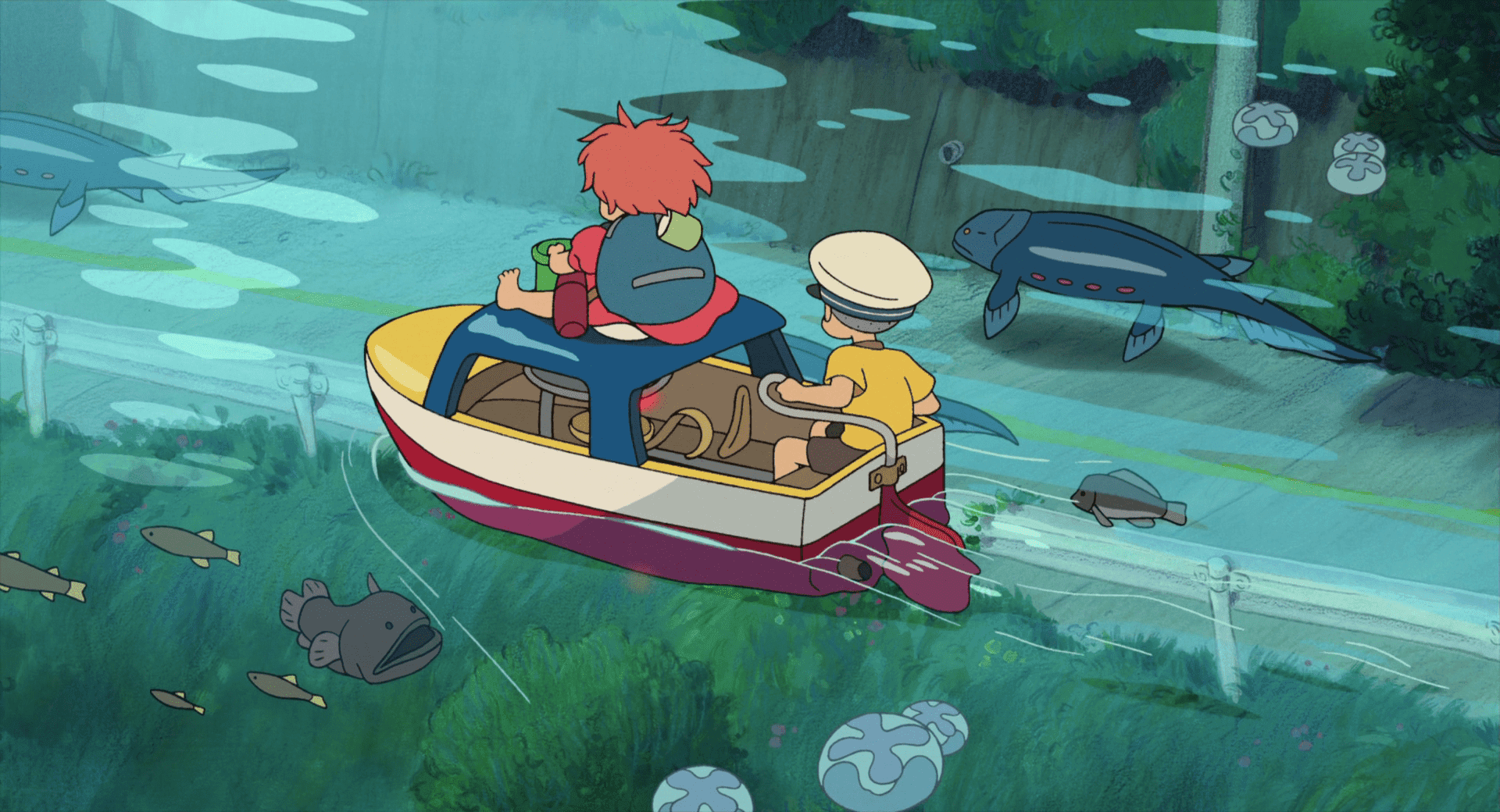

Ponyo and Sôsuke become friends in the meantime and travel around the headland in a small steamboat. Their bond is the emotional epicenter of the film, a friendship that transcends the barriers of species and elements, founded on an unconditional trust and love that only childhood can express with such candor. Their adventure is not an escape, but a journey of discovery and acceptance, a celebration of life in all its forms.

Their love will change the weather and the oceans, but perhaps also a little of our soul. It is in this seemingly simple statement that the true cathartic power of the film resides. Through the eyes of Ponyo and Sôsuke, we are compelled to reflect on the meaning of purity, the strength of innocence, and the capacity of authentic feeling to overcome every barrier, to harmonize even the forces of nature. Their affection becomes a beacon in a storm of transformations, demonstrating that true magic lies in the human capacity to love unreservedly. This is the gift Miyazaki leaves us: not just a film, but an experience that reconnects us to the most authentic and luminous part of ourselves, reminding us of our intrinsic belonging to the great flow of life.

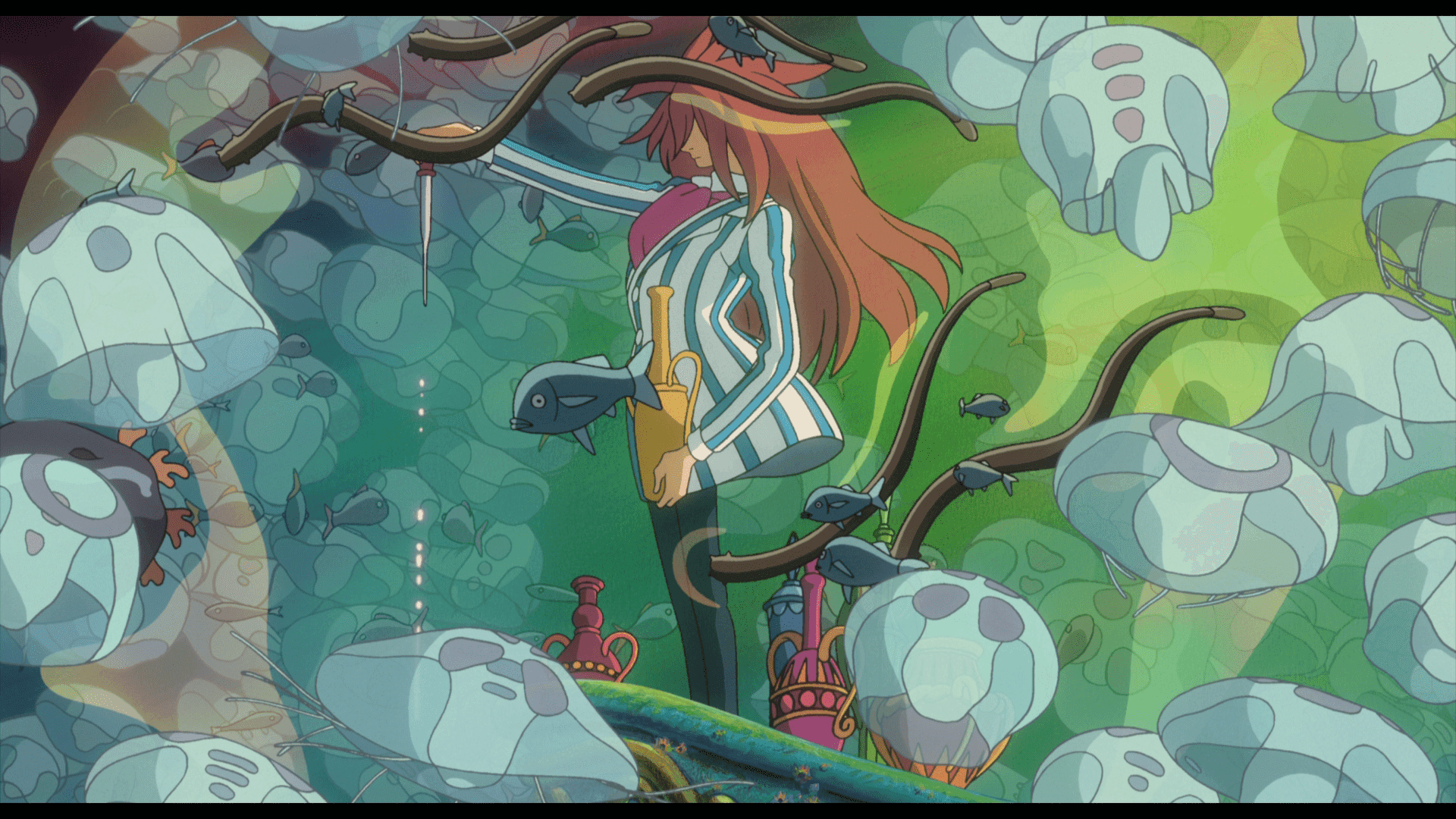

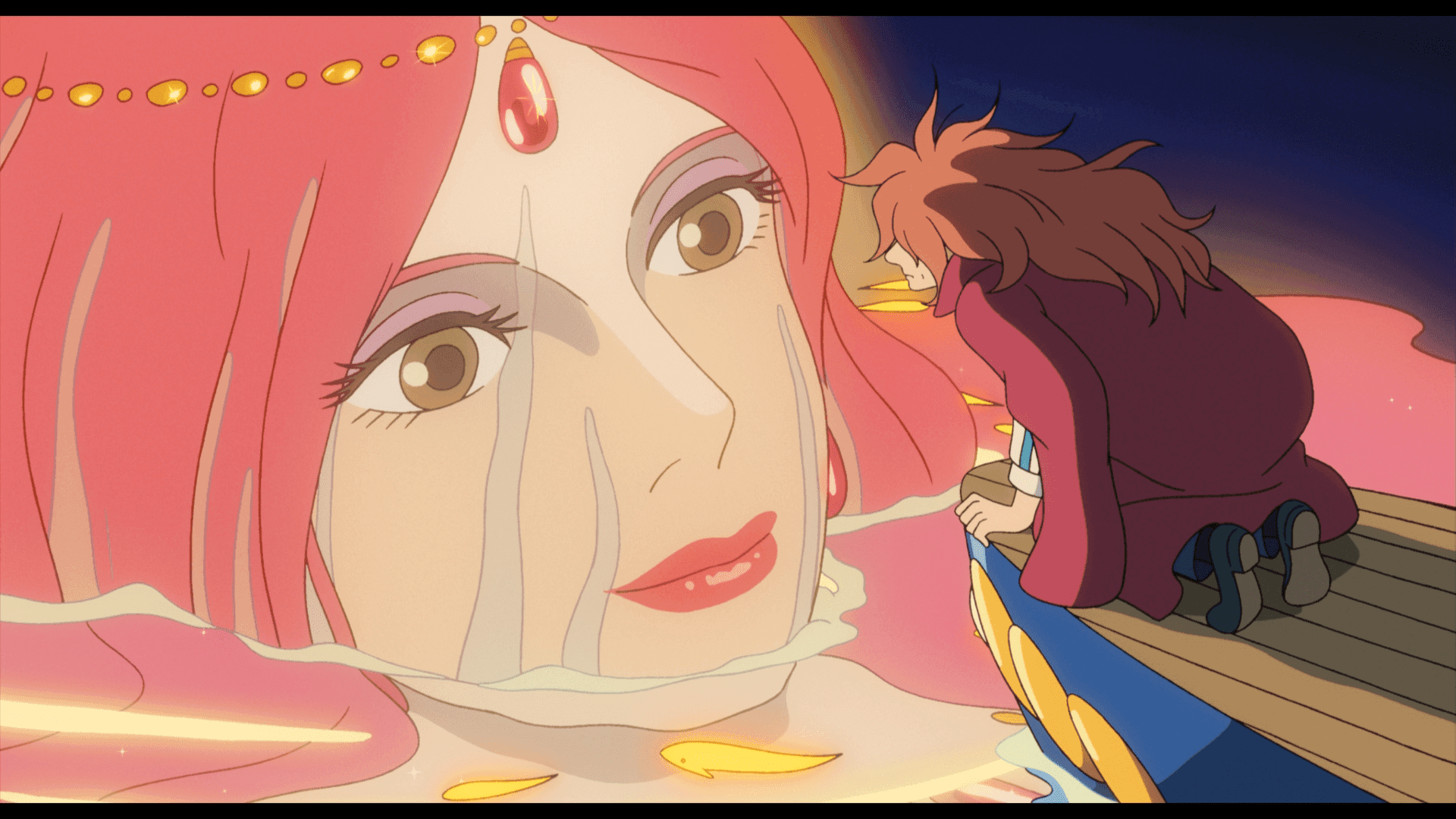

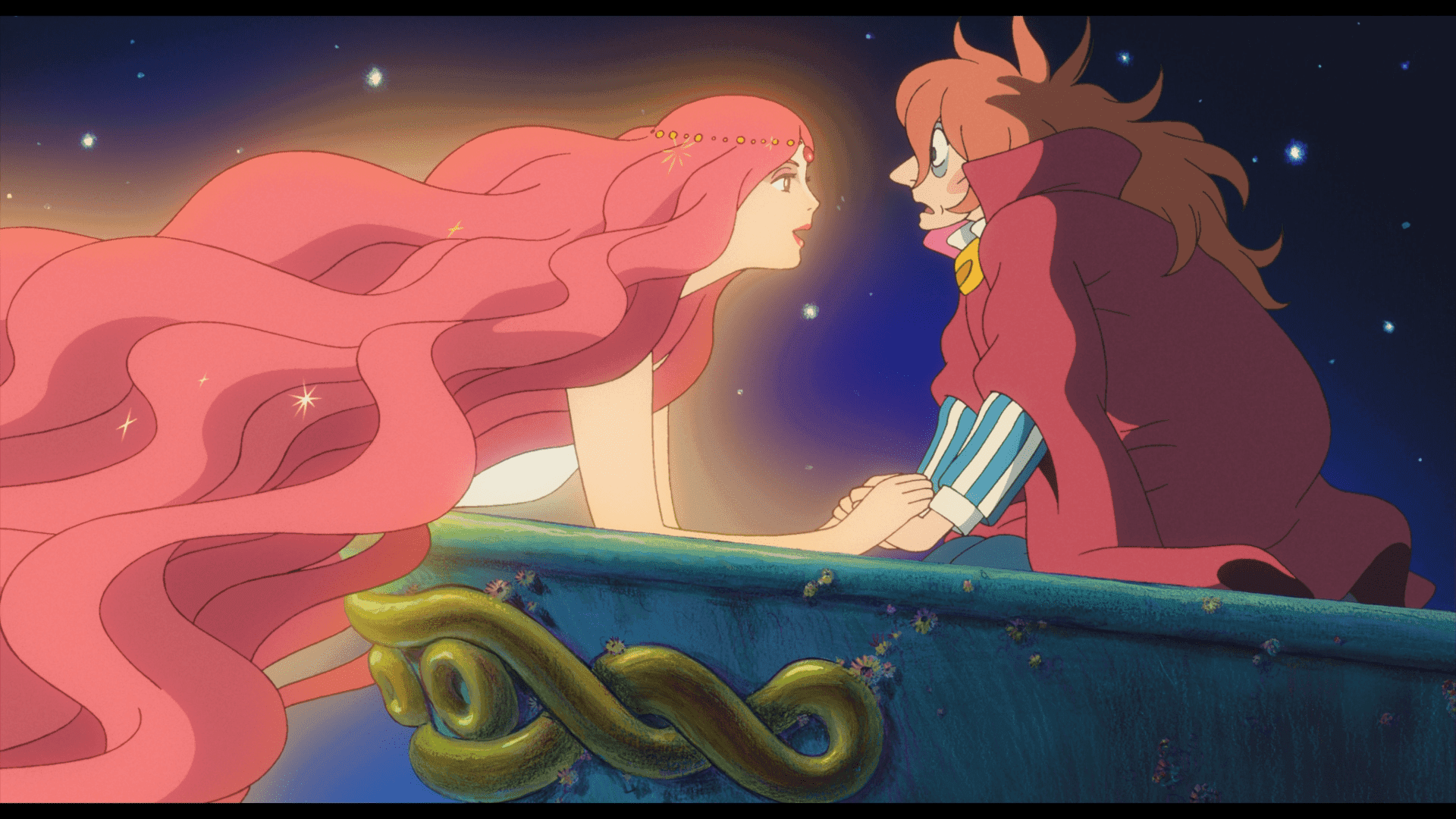

Special mention for the poignant scene of the appearance of Granmamare, Ponyo's majestic motherly creature. It is a moment of rare beauty and profound spirituality. The sea becomes frothy, joyous, playful, changing shape and color, golden fish dart from the foam, while on the surface of the water, the ethereal deity, enveloped in a nimbus of light and serenity, swims with her face turned towards the sky, coming to her daughter's aid. This scene is not only a visual culmination, but an archetypal epiphany. Granmamare is not just a character, but the personification of the Ocean itself, of Mother Earth, and of all the primordial forces of nature. Her appearance evokes a sense of cosmic peace, a rediscovered balance, and her grandeur is not menacing, but reassuring and infinitely wise. She is the quintessence of the immanent divine, an image that resonates with ancient mythologies of the Great Mother, embodying the generative and healing force of the world, capable of containing chaos and restoring order with a single benevolent gaze.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...