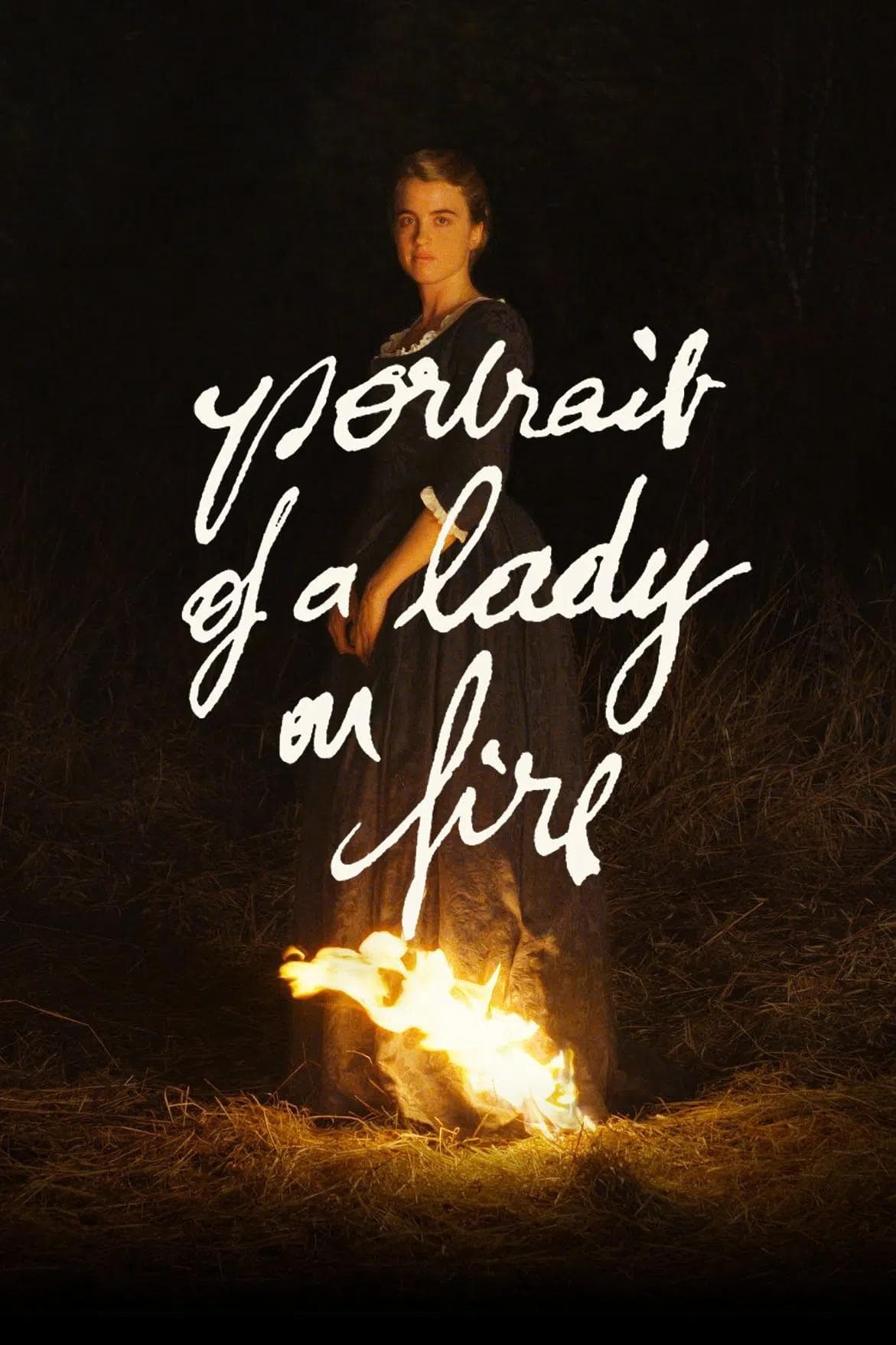

Portrait of a Lady on Fire

2019

Rate this movie

Average: 4.33 / 5

(3 votes)

Director

Portrait of a Lady on Fire is a work of piercing beauty and razor-sharp political intelligence, that uses the language of historical melodrama to compose an aesthetic and existential manifesto on the female gaze, on love as a creative act, and on memory as the only form of eternity. More than a film, it is a sensory and intellectual experience that settles under the skin, continuing to burn long after the credits roll.

The narrative, of an almost mythopoeic simplicity, unfolds in Brittany at the end of the 18th century. Marianne (Noémie Merlant), a painter, is hired by a countess to create the wedding portrait of her daughter, Héloïse (Adèle Haenel). There is a precise and cruel condition: Héloïse, fresh out of the convent and destined for an arranged marriage in Milan, refuses to pose. Marianne must therefore pretend to be a lady's companion, observing her during their walks on the windswept coast and painting her in secret, from memory. What begins as a game of stolen glances – the artist studying her subject, the subject unknowingly revealing herself – transforms into a process of mutual recognition. When the first portrait, technically perfect but lifeless, is rejected by Marianne herself because "it's not her," the pact changes. Héloïse agrees to pose, and from that moment, the relationship between painter and model evolves into a collaboration between equals, and finally into an overwhelming love, consumed on an island outside of time and space, in a parenthesis of absolute freedom.

Sciamma performs an operation as radical as it is subtle. The film is a powerful treatise on the "female gaze," not as a simple inversion of the male gaze, but as an entirely different dynamic, based on empathy, reciprocity, and the absence of hierarchy. In a world where women are objects to be exchanged (Héloïse), instruments for procreation, or professionals limited by their gender (Marianne cannot paint male subjects and signs her works with her father's name), the act of truly seeing each other is a revolutionary act. For a few days, with the countess absent, the island becomes a female utopia. Class distinctions between Marianne, Héloïse, and the young maid Sophie dissolve. Together they read the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice (a perfect synecdoche of their love), play cards, cook, and, in one of the most powerful and unsensationalized scenes, support each other during Sophie's abortion. Sciamma films this moment not as a tragedy, but as an act of female solidarity, then transforms it into a pictorial subject, claiming the representability of a historically erased female experience.

The love between Marianne and Héloïse is depicted with a naturalness and physicality that transcend labels. It is not a "forbidden love" in the melodramatic sense of the term; it is simply a love that exists in a space where the rules of the outside world are temporarily suspended. Its tragedy stems not from a moral judgment, but from the inescapable reality of the patriarchal structure awaiting the protagonists beyond the island. It is a film about the essence of queer love: the creation of a world and a language of one's own, even if only for an instant.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire fits into a lineage of cinema that reinterprets the 18th century not as a mere parade of wigs and corsets, but as a stage for exploring structures of power, desire, and identity. The inescapable reference point is Stanley Kubrick's Barry Lyndon (1975). While Kubrick used period painting (Hogarth, Gainsborough, Zoffany) to create compositions of glacial formal perfection and to tell the rise and fall of a male social climber, Sciamma uses the same period to do the exact opposite: to explore female interiority and untold lives. Other films have explored the century through different lenses: Stephen Frears' Dangerous Liaisons (1988) showed its aristocratic cruelty and manipulation as a social game; The Madness of King George (1994) unveiled its political intrigues; more recently, Yorgos Lanthimos' The Favourite (2018) used grotesquery and black humor to depict power and lesbian desire at Queen Anne's court. Portrait stands apart from all of these due to its minimalism, its almost sacred seriousness, and its total dedication to the protagonists' point of view.

The parallelism between painting and cinema in this film is profound and goes beyond simple quotation. Sciamma and cinematographer Claire Mathon do not merely recreate paintings, but adopt the logic of painting. The light, often natural or from candles, sculpts faces and environments with a precision that evokes masters of the past, creating visual suggestions that are the emotional heart of the film. If for Barry Lyndon the references were explicit, for Portrait we can trace spiritual and stylistic connections. The film is, in fact, an implicit homage to figures such as Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun and Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, immensely talented female painters who had to navigate the restrictions of the French Royal Academy. Their sensitivity in portraying women, often with an intimacy and naturalness absent in their male counterparts, is the same spirit that animates Marianne's gaze.

Ultimately, Portrait of a Lady on Fire is a masterpiece because it manages to be, simultaneously, a universal love story, a precise political analysis, and an essay on the nature of art. It teaches us that to love is to see, that to create is to remember, and that an image can contain the fire of an entire lifetime. Like Orpheus, Marianne makes "the poet's choice," not the lover's: she turns around, loses Eurydice, but transforms her into poetry.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...