Rashomon

1950

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

In 12th-century feudal Japan, a woman is raped and her husband killed. An apparently simple event, yet, in the hands of Master Akira Kurosawa, it becomes the pretext for a dizzying inquiry into the very nature of truth. Kurosawa dissects this crime by laying it out on a microscope slide and providing different versions that will form an increasingly clear and ruthless overall picture, but one never entirely resolved. Kurosawa's genius here lies in his masterful reinterpretation of two tales by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, "In a Grove" and "Rashōmon," blending the investigative structure of the former with the desolate atmosphere and reflection on moral decay of the latter, whose dilapidated gate becomes the metaphorical frame for humanity in ruins.

Every character involved in this affair – the bandit Tajōmaru, the raped woman Masako, the spirit of the samurai Takehiro, the woodcutter, and the monk who witness the trial – is part of a complex semantic mechanism that offers a faint glimmer into the Ultimate Truth of the facts; every source is a piece of the puzzle of Reality. But a puzzle whose pieces never perfectly fit, revealing not so much an intrinsic dishonesty as the inexorable conditioning of perspective and ego. The lie, here, is not pure and simple alteration, but rather a kind of psychological defense, a reconstruction of reality filtered by the need to preserve one's image, to protect one's fragility, or to redeem lost dignity. A story initially dramatic then grotesque, which gradually gains substance in light of the accounts, revealing a crescendo of the absurd and the pathetic that unmasks the intrinsic hypocrisy of human nature.

This is a work that weaves a philosophy according to which reality is made up of innumerable different versions, born of the human psyche and the subjective trajectory each single real event acquires. This "relativity of truth" is not a mere exercise in style, but a profound epistemological inquiry that anticipates by decades cultural and philosophical debates on post-truth. It is no coincidence that the film gave its name to the Rashomon effect, a psychological phenomenon whereby witnesses to the same event report contradictory and subjective versions. A parallel could be drawn with Pirandello's "Right You Are (If You Think So)," where objective truth dissolves in the face of the multiplicity of individual perceptions, or with the fragmented narratives of modernist literature, where individual consciousness becomes the prism through which the world is perceived and reinterpreted.

A taxonomy of diffraction, a pre-established disharmony that stuns us, intoxicates us, leads us to side with one version or another, then leaving us in a limbo of moral uncertainty. It is an intellectual experience that challenges the viewer to confront their own prejudices and certainties, a lesson in humility in the face of the unfathomable complexity of existence. Kurosawa, with the touch of a master painter, uses light and shadow as brushes to depict this ambiguity. Kazuo Miyagawa's celebrated cinematography, with its plays of sunlight filtering through the tree branches and clashing with the deep shadows of the forest, is not just aesthetic: it is a visual reflection of moral confusion and the opacity of human intentions. The blinding glare of the sun perhaps symbolizes the illusion of a clear truth, while the shadows conceal lies and unconfessable secrets.

Kurosawa looms large behind the camera, with shots that are never redundant, aiming to lay bare the human soul and its petty upheavals. The dynamism of the camera, which follows the characters through the dense undergrowth or lingers on their faces distorted by anxiety and deceit, contributes to creating a sense of claustrophobia and inevitability. The setting of the Rashōmon gate itself, spectral and dilapidated, is not merely a backdrop: it is the symbol of a post-war Japan that, like its characters, seeks to reconstruct a truth, a dignity, from the rubble of defeat and disillusionment.

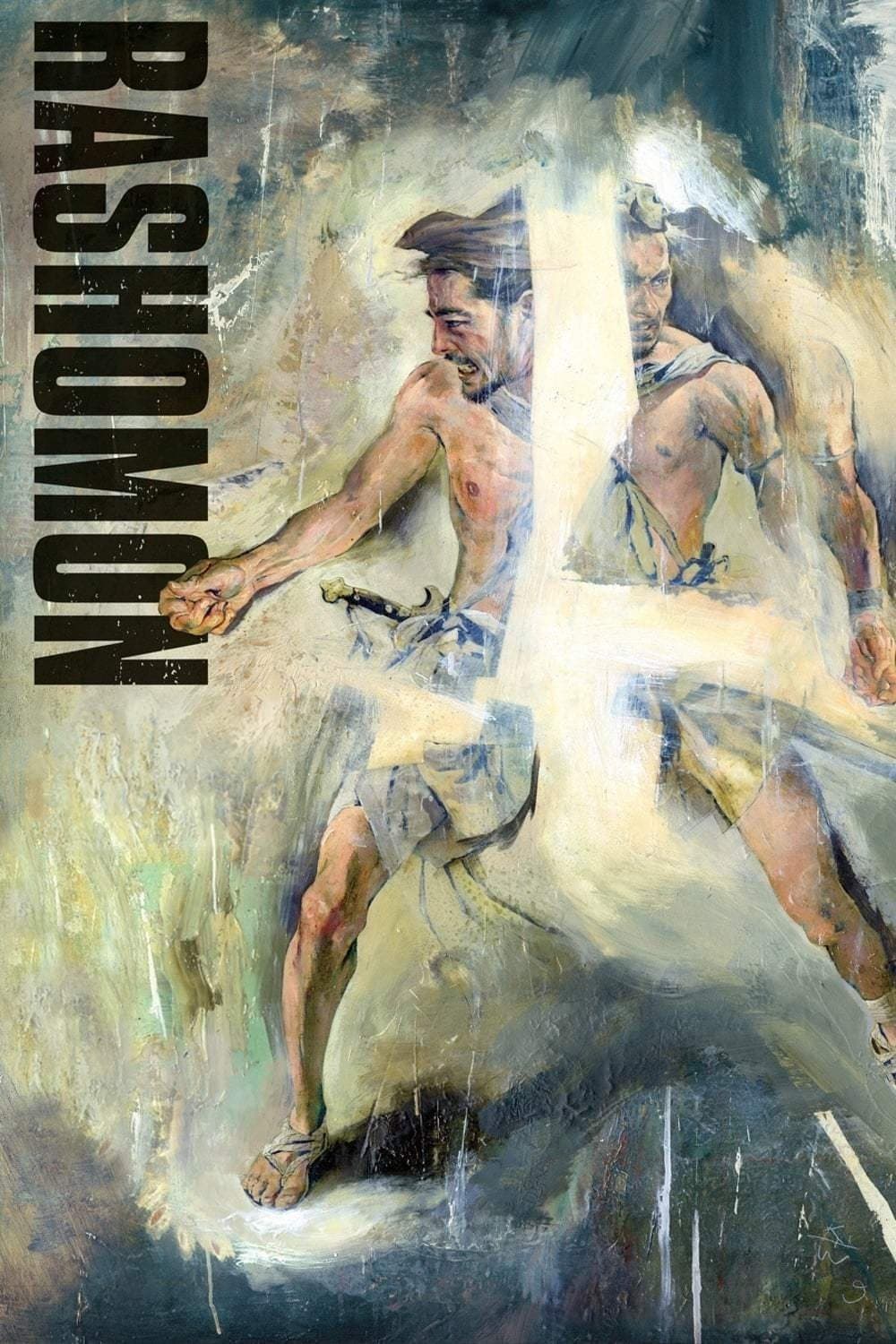

Mention must be made of Toshiro Mifune's performance, a signature actor idealized in much of the Japanese Master's filmography, who here embodies the bandit Tajōmaru with a primordial, almost animalistic physicality. His performance is a whirlwind of wild energy, raucous laughter, and penetrating gazes that capture the essence of a character as brutal as he is, at times, pathetic in his vainglory. His stage presence is so magnetic as to almost steal the scene, yet it integrates perfectly into the mosaic of illusions and self-deceptions woven by the film.

"Rashōmon," awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1951, not only opened the doors of Japanese cinema to Western audiences but consolidated Kurosawa's reputation as one of the greatest filmmakers of all time. Its influence has been immense, shaping generations of directors and influencing narrative across every medium. It remains a timeless warning about the fragility of certainties and the persistent, perhaps eternal, elusiveness of Truth.

Country

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...