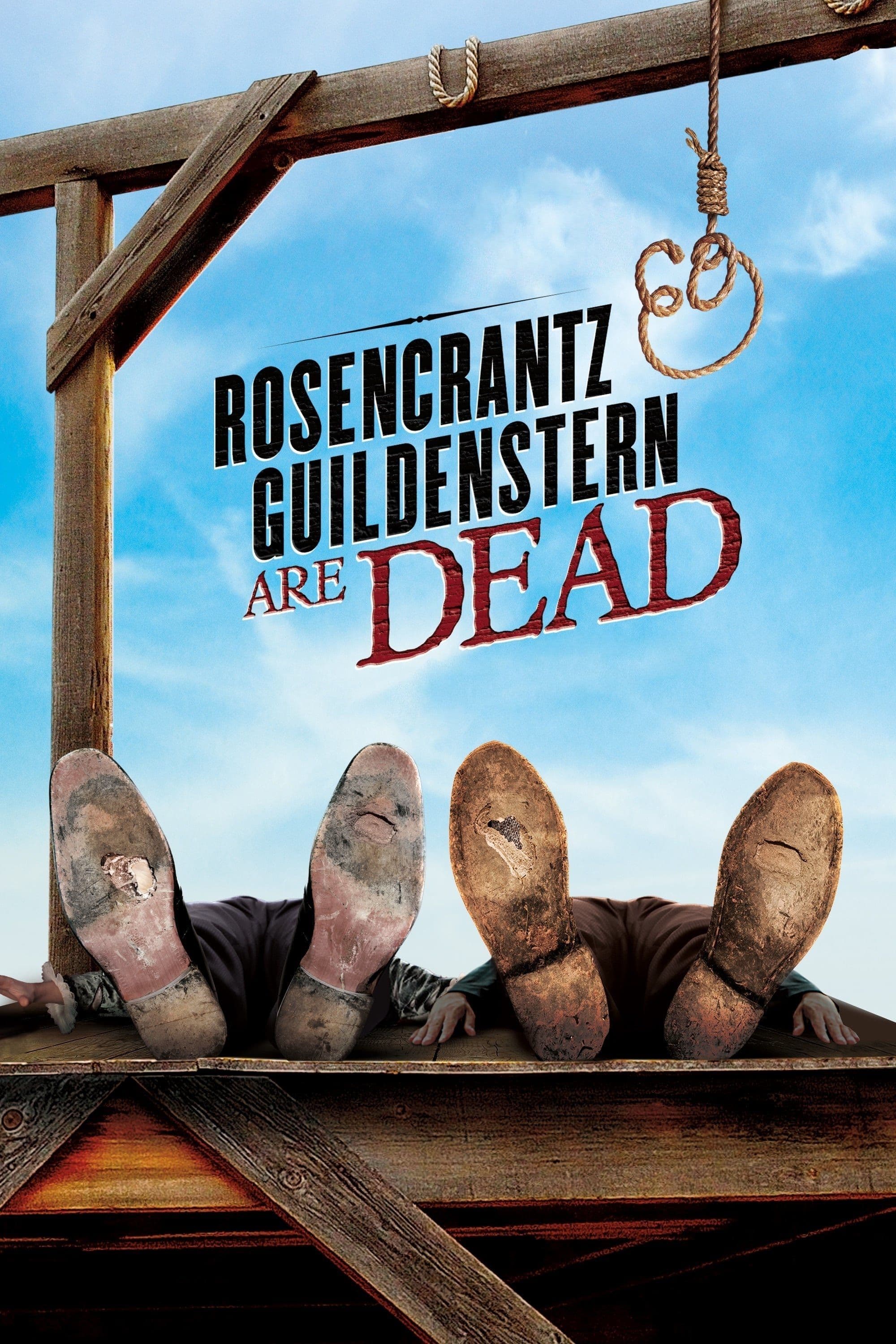

Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead

1990

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A lateral, oblique, incisive view of Shakespeare. It is an unexpected prism, a refraction that deforms and at the same time reveals deeper truths about the human condition and art itself.

This is what the ingenious Tom Stoppard offers us in this film, where he casts his probing eye upon two minor characters from Hamlet and makes them dance through the poetics of an entire century. It is not a mere rewriting, but an audacious hermeneutic operation that filters the Shakespearean tragedy through the lenses of Beckettian absurdism, existentialist nihilism, and playful postmodernism. The two "good lads" from Wittenberg, transformed by Stoppard into archetypes of the oblivious and the disoriented, become vehicles for a kaleidoscopic exploration of the nature of reality, identity, and freedom, mirroring the intellectual anxieties of the twentieth century. It is the poetics of displacement, of being cast into a world devoid of predetermined meaning, a theme dear to thinkers like Camus and Sartre, here presented with an apparent lightness that conceals philosophical abysses.

To be observed carefully for its continuous references to the original text, reinterpreted from various angles, like a blueprint to follow and draw inspiration from, yet dreamily detached from the story being told. Stoppard plays with Shakespeare's diegesis, showing us fragments of the main drama as ghostly apparitions, events of which Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are tangentially aware, but never fully involved or comprehending. It is a masterful lesson in intertextuality, where the "behind the scenes" becomes the main stage, and the tragedy of Elsinore manifests as an incomprehensible background noise, a destiny that unfolds elsewhere, yet inexorably draws them in. Their not being at the center of the action, despite being functional to it, makes them perfect masks for contemporary man, a passive spectator of a story too grand for him.

Also interesting is the operation of building two identities anew, starting from two minor characters of the Shakespearean narrative and elevating them to eccentric protagonists of a possible but improbable world. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are not merely comedic figures, but incarnations of ontological dilemmas. Who are they outside of their Shakespearean function? Their very existence is defined solely by their relationship with Hamlet, by their designation as "those who are not Hamlet." This search for an autonomous identity, hindered by their own literary predetermination, is the pulsating heart of the comedic drama. They are condemned to be the "schoolfellows," the pawns, and their rebellion, purely dialectical and intellectual, is always destined to fail.

A kind of Hamlet spin-off, to put it in modern terms, but in reality a sophisticated meta-narrative that deconstructs not only the Shakespearean drama, but the very nature of fiction and reality. Stoppard does not merely reuse characters; he empties them and fills them with new anxieties, confronting them with unanswered questions about their raison d'être, about the inevitability of the fate written for them.

The rhetorical flow of the dialogues and the theatrical inspiration in the verbal dualism of the two contenders are exciting, almost a challenge between two consummate sophists. Language is the true battlefield, the arena where intellectual duels of extraordinary brilliance are fought. The rapid-fire exchanges are swift, often circular, imbued with paradoxical logic, with wordplay that both reveals and conceals. One perceives the influence of Beckett's "theatre of the absurd," particularly "Waiting for Godot," not only in the dynamic of the duo awaiting meaning or action, but also in the use of language as a tool for philosophical exploration and at the same time as an insurmountable barrier between individuals and the understanding of the world. The humor springs from the despair of those who try to impose a rational order on a universe that stubbornly evades all categorization.

Original and moving in its bombastic non-sense, its semantic collapses, its dialogic rebounds. These "collapses" are not random; they are testimony to the fragility of language as a tool for truth, its failure to capture the complexity of reality. The characters get lost in the labyrinth of logic, in verbal convolutions, transforming discourse into a cage from which they cannot escape, trapped in their own arguments.

Memorable is the scene where Rosencrantz finds a coin on the road and repeatedly tosses it, always getting heads, much to Guildenstern's disbelief: probability does not exist, it is merely a physical attribute, sequentiality is the ghost that envelops and devours the world. This sequence is the philosophical core of the film, a moment of pure metaphysical vertigo. The systematic violation of the laws of probability is not a simple magician's trick; it is the visual staging of the idea that the two characters are prisoners of a predetermined fate, that their lives are not the result of free will but of an already written script. It is a powerful metaphor for determinism, for the sensation of being puppets in someone else's drama, where even the fundamental laws of the universe bend to the will of an invisible author. Guildenstern's anxiety in the face of this statistical anomaly is our own anxiety when confronted with a world that eludes us, that does not respond to our rational expectations. It is the nightmare of discovering that even chance is an illusion, and that every coin toss is already decided.

Tom Stoppard, a man of theatre lent to cinema, creates an original and fresh work with which to pay homage to the Master of every dramatist, but also to reassert his own genius. His transition from stage to screen, here as director as well as screenwriter, is exemplary. Although the film maintains a theatrical imprint, Stoppard makes the most of cinematic language: the fluidity of the shots, the evocative power of the costumes and sets that recall Flemish painting, the use of editing to accelerate the comedic rhythm or to suspend time in anticipation. The cast, with a dazzling Gary Oldman and Tim Roth in their roles and an over-the-top Richard Dreyfuss as the Player King, further elevates the material. Oldman captures the intellectual frustration and existential agony of Guildenstern, while Roth embodies the blissful unawareness and almost childlike simplicity of Rosencrantz. Their chemistry is the fuel that powers the entire narrative mechanism. The film is not just a brilliant stylistic exercise or an academic homage; it is a profound reflection on life, death, the meaning of being, and our place in the immense, incomprehensible, sometimes comic, sometimes tragic, drama of existence.

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...