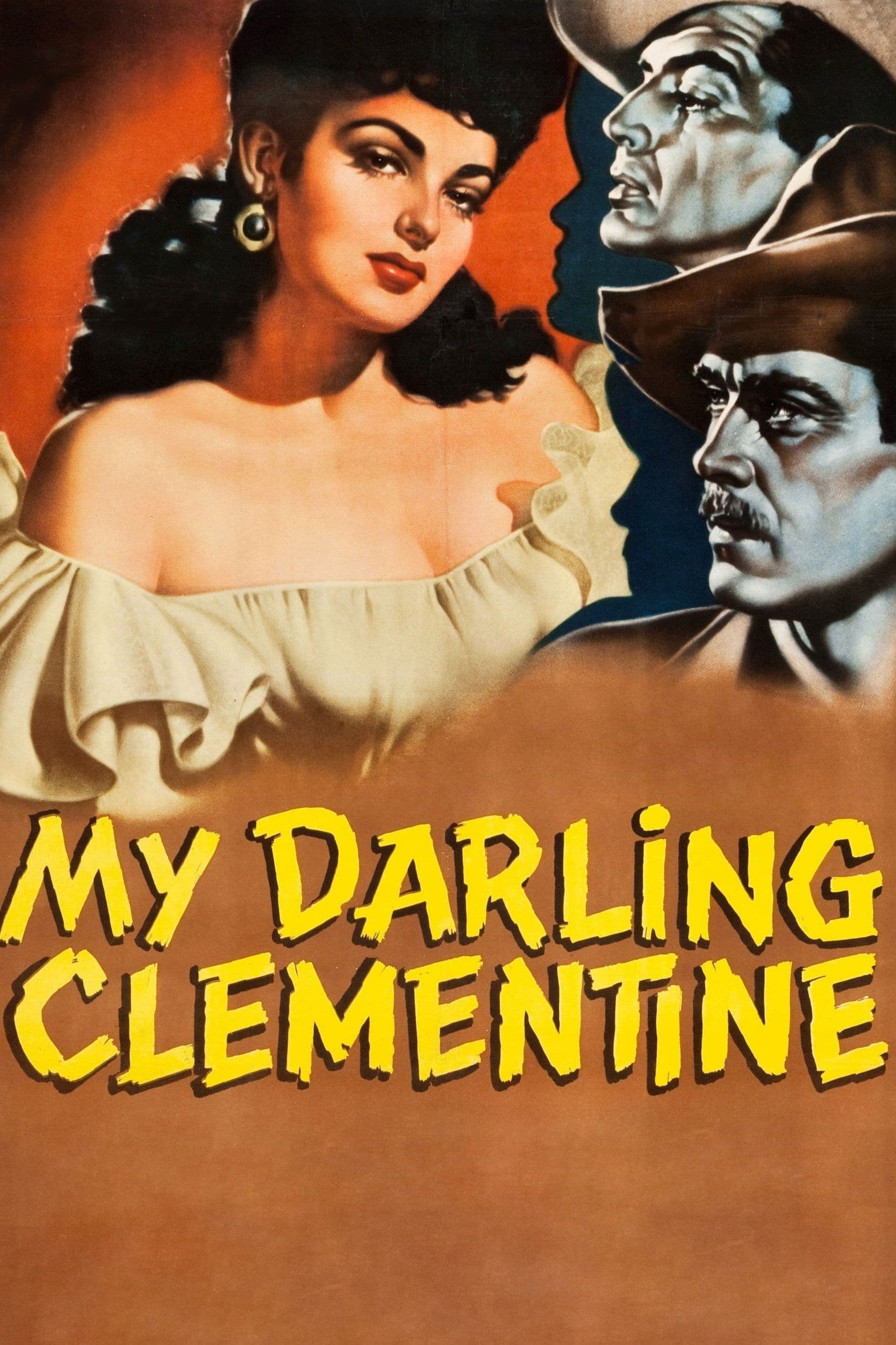

My Darling Clementine

1946

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Ford, in his third Western film, outlines his poetics through the myth of the Tombstone gunfight, a legendary event also depicted by Sturges in Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. But while Sturges's film, though commendable, focuses on the turmoil and inevitability of the showdown, Ford elevates the episode to a cornerstone of a broader reflection on the birth of American civilization, on the transition from wild chaos to the fragile, yet necessary, imposition of law. It is not just the chronicle of a conflict, but the genesis of an archetype, the genesis of a nation.

My Darling Clementine is a work that alternates powerful, vivid digressions with moments of intimate introspection, where Ford's restless eye delves into the emotional recesses of the protagonist, laying bare his contradictions and human impulses. Indeed, those vivid digressions are authentic brushstrokes of light and shadow, moving canvases that draw upon the grandeur of the Southwest landscapes, and particularly the almost sculptural majesty of Monument Valley, which here, under Joseph MacDonald's masterful cinematography, is not merely a backdrop but a character in its own right, its rock formations rising like natural cathedrals, silent witnesses to the eternal struggle between man and the frontier. Ford imbues each shot with an almost biblical solemnity, transforming the wild West into an epic stage for dramas both private and universal. Introspection, on the other hand, manifests in the protagonist's reluctance, in his journey from a simple cattleman to a sheriff, a path not dictated by ambition, but by the gravity of sorrow and moral necessity.

Wyatt Earp is determined to avenge his brother's death, which occurred at the hands of a gang of outlaws, the notorious Clantons. To do so, he does not hesitate to get himself elected sheriff, taking on a burden that goes far beyond simple reprisal. His is not a swaggering heroism, but a subdued dignity, a sense of duty that elevates him above the pettiness of personal revenge to embrace an ideal of justice and order. Earp's arrival in Tombstone, with his brothers and their modest cattle herd, is an image of vulnerability and aspiration for quietude that will be brutally shattered. Loss, in Ford, is often the catalyst for the birth of a hero—not a hero of brawn, but of conscience.

He will track down the gang and confront them in Tombstone, able to count on the help of an alcoholic doctor and his trusty Colt. Doc Holliday, played by a magnificent Victor Mature, is not here the romantic bandit or mere armed enforcer, but a Shakespearean figure, an intellectual consumed by illness and cynicism, whose friendship with Wyatt Earp is woven with a mutual respect that transcends their differences. He is the melancholic counterpoint to Earp's granite-like determination, a soul torn between dissoluteness and a lingering sense of honor, whose presence lends an even deeper emotional layering to the drama. The dance between Wyatt and Clementine in the saloon, as well as the sequence of the church under construction, are emblems of this nascent civilization, small, moving glimmers of a better future, in a world still dominated by mud and violence. Ford doesn't just show the gunshots, but the foundations upon which a society will be built. The dichotomy between the refined Clementine Carter, a symbol of civilization arriving from the East with its promises of education and culture, and the passionate and tragic Chihuahua, an embodiment of the wild and untamed beauty of the West, adds further nuances to the social and emotional landscape, emphasizing the choice between progress and archaism, between law and anarchy.

Faced with such a film, one has the distinct impression of witnessing something subtly grand, a sense of greatness in the making that permeates the entire work and imbues it with an unparalleled, almost mystical charm. This grandeur is not ostentatious, but stems from the attention to detail, from the visual power of every single frame that imprints itself on memory like an engraving. It is the breath of an epic being written, the sensation of being privileged witnesses to the genesis of an American myth. Ford, with his unmistakable lens, does not merely narrate, but evokes, transforming a historical episode into a universal legend. Every gesture, every silence, every gaze, especially Henry Fonda's unforgettable ones as Earp, contributes to creating this almost sacred aura, where the landscape itself seems to vibrate with profound meaning.

Ford, master of a certain type of West, a kind of chiaroscuro zone of the soul, accompanies us like an elegant host through his captivating stories, and we, docilely, more than willingly let ourselves be guided into this wild world. This Fordian "chiaroscuro" is not just a matter of cinematic lighting, but a stylistic hallmark that permeates the entire narrative, highlighting moral ambiguities, the struggles of civilization, the intrinsic melancholy of a world disappearing to make way for something new, and not necessarily better. It is the West of toil, of sweat, of small triumphs and great losses. Ford offers us not an illusion, but a profound and complex vision of American roots, forged in the crucible of the frontier. His post-war gaze was imbued with a search for foundational values, for an America that could rediscover its essence in the simplicity and harshness of its genesis. In this 1946 masterpiece, Ford not only defines the contours of the classic Western but elevates its stature to a universal drama about man, his destiny, and his inexhaustible, and sometimes painful, search for a place to call home.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...