Sons of the Desert

1934

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Sons of the Desert is not only undoubtedly the most celebrated and acclaimed feature film by the tried-and-tested duo Laurel & Hardy; it is an authentic masterpiece that crystallizes, in an hour and ten minutes of pure cinematic joy, the apex of their comedic art. In a tumultuous era of transition for Hollywood, marked by the advent of sound which had claimed not a few victims among silent film stars, Laurel and Hardy demonstrated a versatility and resonance that transcended mere physicality. Director William A. Seiter, with a wisdom not common to all practitioners, understood that he had to almost blindly entrust himself to their extraordinary comedic power, true walking architectures of laughter. Their collaboration went far beyond simple acting: Stan Laurel, in particular, was a relentless perfectionist, a true "gag-man" who infused his own innate creativity into the storyboard, made of irresistible gags and that almost choreographed precision that transformed every movement, every expression, into a musical note in a symphony of controlled chaos. Oliver Hardy, with his mastery of reactions – from the slow "slow burn" to the lightning-fast "double take" – completed the picture, making every interaction a lesson in comedic timing. The film, with its plot that is only seemingly simple but disarmingly effective, its paradoxical situations that accumulate like avalanches, and its memorable characters carved into the collective imagination, is a concentrate of pure comedy. It is a comedy born from a perfect narrative and directorial mechanism that not only synergizes with the creative force of the two stars, but enhances every nuance, transforming the mundane into the epic, the pathetic into the sublime.

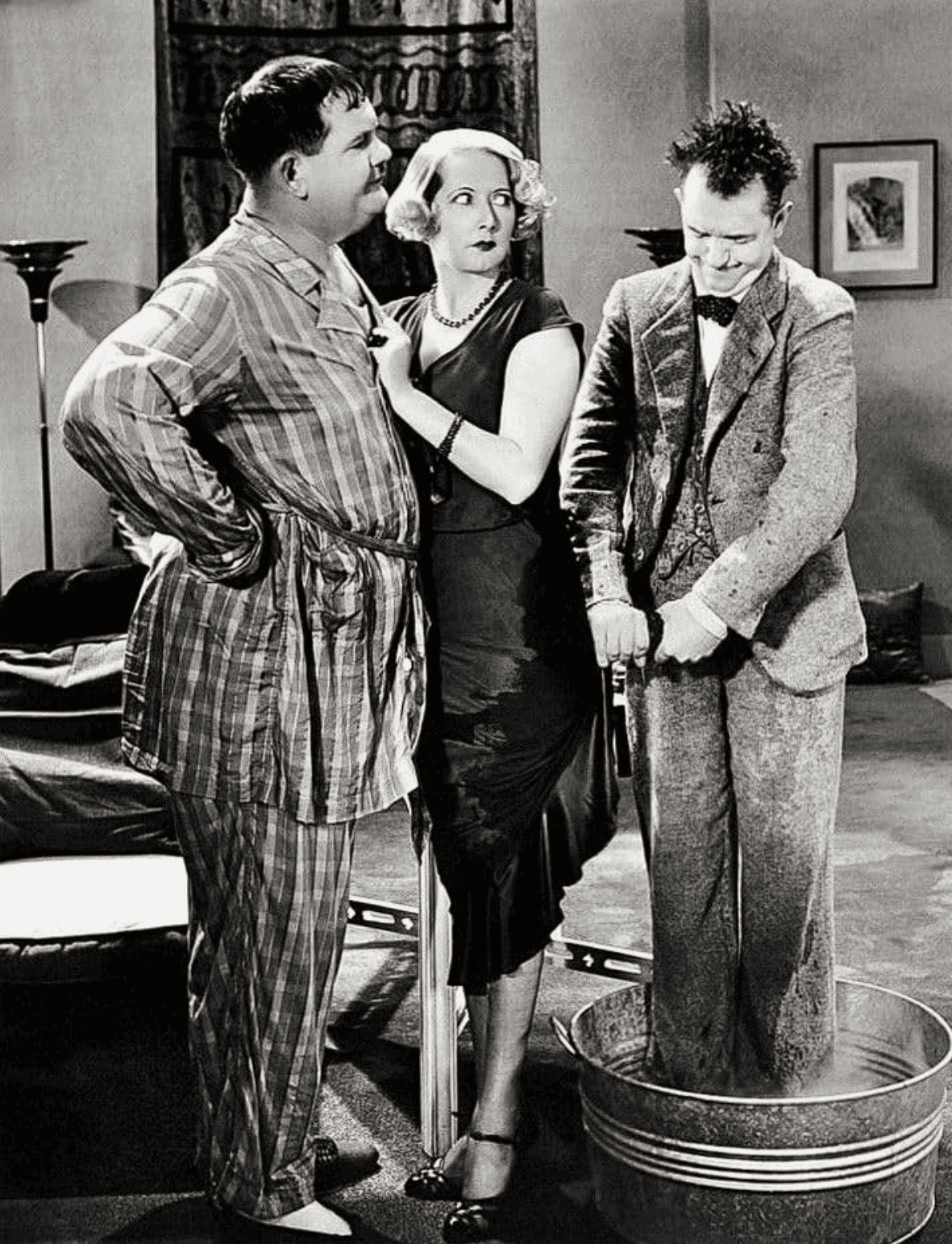

The story, despite its apparent linearity, reveals itself as an ingenious fresco of marital dynamics and male aspirations in an era of profound social transformations. We are faced with two archetypal henpecked husbands, played by Laurel and Hardy with an irresistible blend of pathos and cunning, condemned to live under the yoke of two tyrannical wives, one of whom is played by Mae Busch, who embodies the perfect comedic virago with sublime fury. The two, with the secret complicity of their affiliation with the Masonic lodge "Sons of the Desert," a sanctuary of (presumed) virility and male camaraderie, long for escape from domestic and marital routine. Their objective: to reach Honolulu, host of their lodge's annual convention, an Eden of freedom far from slippers and marital squabbles. To reach their desired destination, they devise a plan diabolical in its simplicity: feigning that Oliver is afflicted by an exotic illness, in need of a transoceanic cruise for a cure. This ploy, as clumsy as it is desperate, triggers a chain reaction of lies and misunderstandings that is the pulsating heart of the farce. The beauty lies precisely in the inexorable progression of deception: every lie begets another, every attempt to remedy leads to a greater disaster, in a crescendo of absurd and embarrassing situations. It is a mechanism reminiscent of the most refined comedies of errors, but with the unique imprint of their comedy, which makes the inevitable discovery of their subterfuge not a drama, but the apotheosis of the ridiculous. The consequent return home, drenched and forced into an exemplary humiliation, is not just a punishment, but the crowning of a cycle of rebellion and submission that repeats infinitely in their comedic universe.

Sons of the Desert is, therefore, much more than a mere comedy film; it is a work that literally made comedy history, an archetype that continues to entertain and make audiences of all ages and latitudes laugh, transcending linguistic and cultural barriers. Laurel & Hardy's comedy, far from being merely superficial, is based on the meticulous and ingenious contrast between their personalities: Oliver, the pompous and perpetually defeated "dignified buffoon," convinced he is the brains of the duo, and Stan, the naive but sometimes inexplicably shrewd "wise fool," whose convoluted logic always leads to disaster. It is precisely in their ability to create paradoxical situations, and to react to them with a comical and never vulgar despair, that the universality and timelessness of their art reside. The film, with its apparent lightness and sharp irony, is a kind of modern moral fable that reminds us of the cathartic importance of being able to laugh at ourselves and our most human weaknesses, our petty rebellions, and our inevitable defeats.

This timeless classic has not only influenced generations of comedians, from Jerry Lewis, with his mix of childlike clumsiness and pathos, to Jim Carrey, with his exaggerated, almost cartoonish mimicry, but continues to be a benchmark for slapstick comedy. However, defining their comedy as pure slapstick would be reductive: it is refined slapstick, based not on gratuitous violence, but on the psychology of the characters, the chain reactions of their actions, and the slow but inexorable build-up of the gag, often culminating in a mutual destruction of objects (the hat sequence is emblematic) that becomes a metaphor for the destruction of their precarious balance. The film also stands out for its ability to create an autonomous comedic universe, a microcosm populated by memorable characters and surreal situations, with its own rules and a recognizable language, made of looks at the camera, exasperated sighs, and whimpers.

In this universe, the Masonic lodge "Sons of the Desert," with its bizarre rituals and rigidly observed conventions (and unfailingly broken by Laurel & Hardy), becomes the perfect microcosm in which the two move with their usual clumsiness, amplifying their existential discomfort in a context of feigned solemnity, creating hilariously comedic situations. This setting is not accidental: the film offers an ironic and insightful look at 1930s American society, a period marked by the Great Depression and a strong need for escapism and lightness. Its social conventions and hypocrisies are lampooned with sagacious humor. Laurel and Hardy's authoritarian wives, while being comedic characters, represent a sharp satire of the dominant and emasculating female figure, typical of a certain male imagination of the era, but also a reaction to growing female emancipation. Their domestic fury is the price to pay for the two husbands' vain search for freedom, transforming their escape not into liberation, but into a perpetual cycle of rebellion and resignation. In this sense, Sons of the Desert is not only a comedic gem, but also a subtle social commentary on the nature of human relationships, on the illusions of freedom, and on the eternal conflict between the desire for escape and the inescapable reality of responsibilities.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...