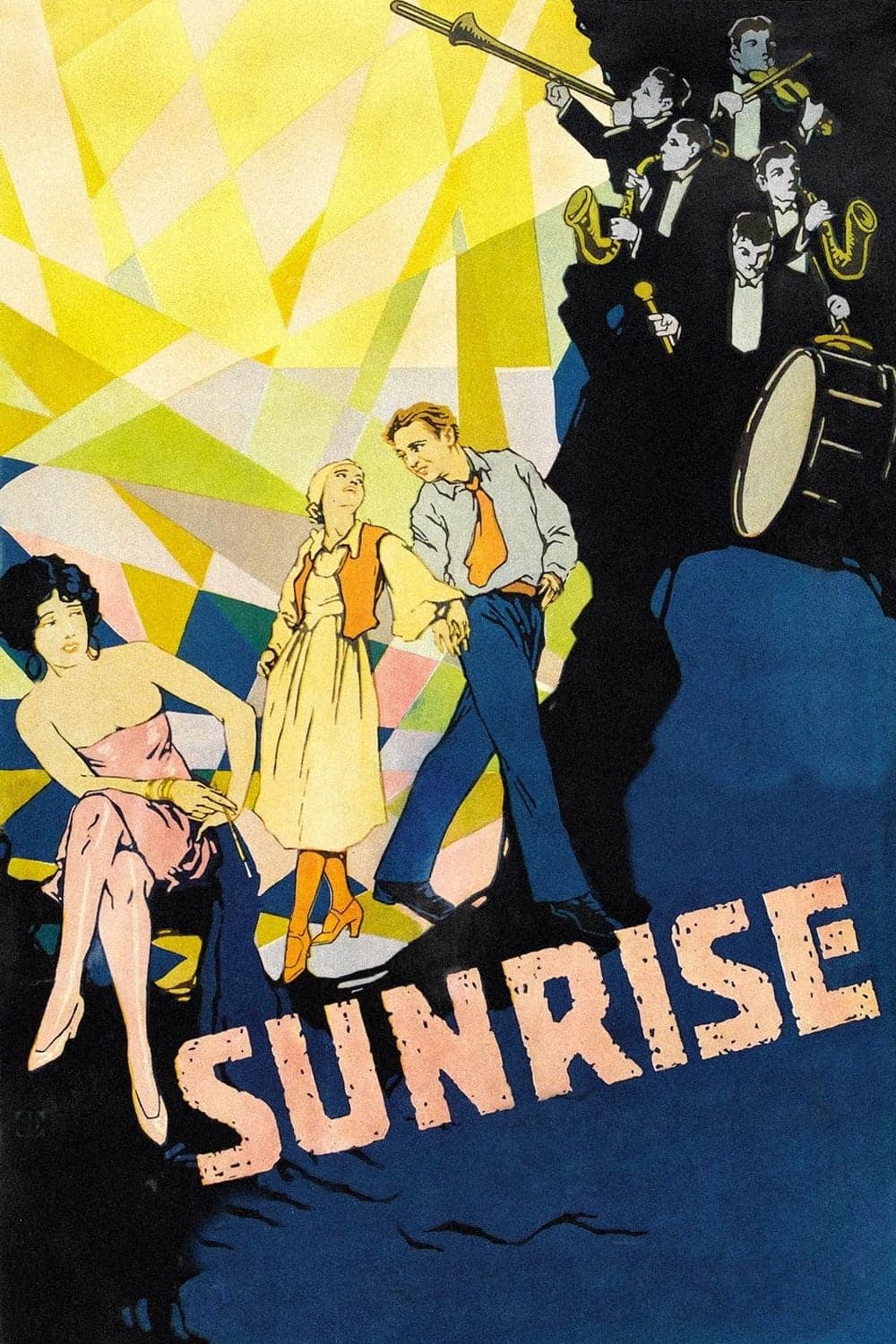

Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans

1927

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Sunrise perhaps represents the first sumptuous attempt to transcend the expressive medium of the camera to achieve an innovative and sensational artistic result. Murnau shot this film in the new Fox studios in the United States, with obsessive technical mastery, exploring every sequence with creative fervor, in an attempt to explore a new narrative path that would restore to the screen the genesis of a love in every dramatic facet. His celebrated "Entfesselte Kamera" – the unleashed camera – was no longer a mere passive recorder, but a dynamic entity, almost a character itself, capable of dancing among the characters, delving into their psyches, reflecting anxiety and joy with unprecedented fluidity. This visual audacity, which Murnau had already masterfully experimented with during his German Expressionist period – one only needs to recall the sublime The Last Laugh – here finds a new and more opulent framework, transforming the cinematic space into a true stage of the soul. With Sunrise, Murnau not only tells an intense and passionate love story but creates a unique visual and emotional experience, a true symphonic poem for images, which anticipates and influences countless future works.

In the film's subtitle, "a song of two humans," perhaps lies the hermeneutic key to approaching the work. With this simple slogan, Murnau suggests that his film is not merely a narration of a story but a total work of art that engages all the viewer's senses. The music, photography, acting, and set design merge into a visual and sonic symphony whose aim is to convey the universality of love and human emotions. The term "song" evokes the idea of a melody, of a harmony that goes beyond words, a primordial invocation to the purest and most complex feelings. Love, in this sense, becomes a universal language, capable of transcending cultural and social barriers, geographical specificities, and historical contingencies. Murnau, through the images and emotions of his characters – archetypes rather than defined individuals – creates a kind of visual score that allows us to understand the depths of the human soul, its eternal oscillation between light and shadow, between sin and redemption. It is a hymn to the salvific power of affection, a celebration of the spirit's resilience in the face of temptation.

The story, based on Hermann Sudermann's novel “A Trip to Tilsit,” centers on a peasant couple whose domestic tranquility is disturbed by the arrival of a city woman. This femme fatale, a cinematic archetype destined to proliferate, is not merely a seductress here, but a catalyst, a destructive force that, paradoxically, propels the protagonists towards a necessary rebirth. She will seduce the man and, in a sensual whirlwind of passion, induce him to rid himself of his old life by killing his wife, then follow her to the metropolis. The man, initially resolute, will waver before his ungrateful task, and will rediscover his wife's love precisely in the city that was meant to welcome him as a wife-killer, in a psychological and spatial reversal of extraordinary effectiveness. The dichotomy between the placid, almost idyllic, yet also suffocating countryside and the chaotic, vibrant, almost Dionysian metropolis itself becomes a metaphor for the couple's inner journey, an initiatory path that will lead them to rediscover themselves and each other. The city is not merely a backdrop, but a pulsating entity, an initiatory trial made of dazzling lights, anonymous crowds, and unexpected moments of joy and rediscovery.

Some scenes are sublime, such as the attempted murder in the boat on the lake, with close-ups of the man's sardonic face and his paroxysmal hesitations before his predetermined goal. Here, Murnau's direction reaches unparalleled heights of lyricism and psychological tension, transforming the water's surface into a mirror of inner turmoil and the boat trip into a rite of passage towards the moral abyss. But it is precisely from this abyss that the possibility of redemption emerges. The urban odyssey that follows, with the celebrated amusement park sequence and the unbridled dances in the city, is a vortex of images expressing liberation and newfound lightness, a visual and emotional counterpoint to the initial heaviness. Murnau, through refined direction and skillful use of images – ranging from elaborate miniatures and forced perspectives to create the city's majesty, to superimpositions that evoke dreamlike states of mind – creates an atmosphere of dream and poetry, which emotionally engages us and invites us to reflect on the fragility of love and the complexity of feelings. The play of light and shadow, so intrinsic to Expressionist language, is here elevated to a narrative and psychological tool, shaping not only the environments but the very souls of the characters. The film is a hymn to life and hope, a work that reminds us that even in the darkest moments it is possible to find the path to redemption, that love, when authentic, can overcome all adversity and rise from its ashes. This film made Murnau a celebrated artist even in Hollywood, winning the first and only Oscar for "Unique and Artistic Picture," contributing to give new roaring vitality to the Seventh Art and demonstrating, in the transition from silent to sound film, that true cinema has always been, and always will be, a universal language that speaks directly to the soul. Its influence extends far beyond its time, carving a deep furrow in cinematographic language and inspiring generations of filmmakers with its formal audacity and moving humanity.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...