The Big Lebowski

1998

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Directors

The Coen brothers' aesthetic journey, from Blood Simple to Fargo via Miller's Crossing and Barton Fink, has always been mottled with an underlying comedy, an ironic verve that pulsates through their stories, tempering their dramatic intensity and eroding their formalism. This peculiar sensibility, which in other hands might have seemed cloying or jarring, has been their trademark, a distorting lens through which to observe the desolate grandeur of provincial America, its silent pathologies, its characters verging on the grotesque. In these previous works, laughter often emerged as a nervous gulp, a defense mechanism against impending horror or absurdity, a bitter and detached commentary on the inevitable human stupidity that permeates even the darkest plots.

In The Big Lebowski, this vis comica finally comes to light in all its candid splendor, no longer as a subtext but as the very fabric of the work. A comedy, if you will, of multiple registers: from boisterous sarcasm to the most irreverent parody, transitioning through the subtle irony hidden in every dialogue, in every glance, in every non-sequitur. The Coens do not merely narrate a story; they construct a postmodern fresco of turn-of-the-millennium America, a pastiche of genres – noir, the comedy of errors, the "stoner" film – that merge in an explosion of surreal genius. It is a celebration of the absurd, a hymn to philosophical laziness, a manifesto for the acceptance of chaos as the only constant.

At the center of this off-kilter universe, the Coens craft a memorable character, an icon destined to transcend the screen: Jeffrey "The Dude" Lebowski, a lazy, irreverent, and slovenly layabout who drifts through life leveraging the inertial force of his indolence. The Dude is not merely lazy; he is a living anachronism, a relic of 1970s counterculture floating intact – or perhaps hardened – in the cynicism of the 1990s. His "sacred quietude" is not mere apathy, but a form of passive resistance, a Zen philosophy of inertia in a world obsessed with doing, having, and proving. His disinterest in bourgeois conventions and the pursuit of success elevates him, paradoxically, to a kind of unintentional sage, a modern Ulysses who, instead of seeking a return to Ithaca, merely seeks his bottle of Kahlúa and a good rug.

Our Dude (in Italian, he was awkwardly translated as "drugo," mimicking Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange and perhaps losing some of the original's spontaneous nonchalance) will soon, and against his will, find himself embroiled in stories of money, mobsters, and reprisals that will endanger his sacred peace of mind. The plot, with its MacGuffin of the urinated-on rug, is an ingenious parody of the classic hard-boiled genre, where the cynical and disillusioned detective is replaced by a pot-smoking bowler who struggles to distinguish right from wrong, or even one Lebowski from another. The plot unfolds in a hilarious mise en abyme of mistaken identities, eccentric figures gravitating around a distorted idea of wealth and power, and German nihilists with a very clear opinion on the value of human life.

A film that highlights Jeff Bridges' mimetic skill, as he does not merely play The Dude but seems to embody him, with a disarming naturalness that makes him immediately credible and lovable. Alongside him, a supporting cast that is an authentic gallery of unforgettable characters: John Goodman as Vietnam veteran Walter Sobchak, a militaristic and pragmatic friend, rigidly anchored to self-imposed rules and unresolved traumas that explode in performances of uncontrollable rage; Steve Buscemi as the innocuous and unheard Donny, and a splendid cameo by John Turturro as the Hispanic bowler Jesus Quintana.

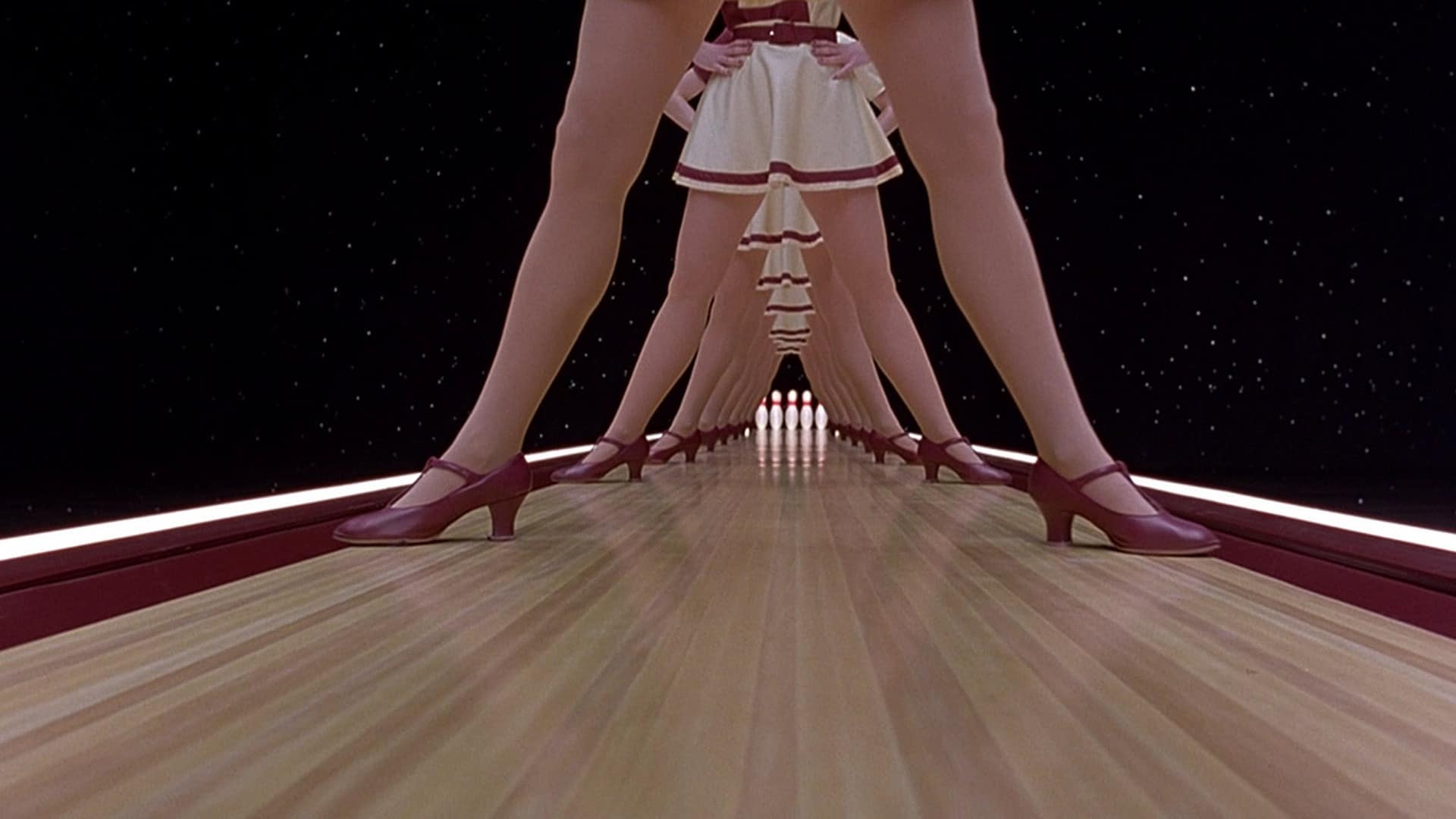

Memorable is Quintana's strike scene with his unique bowling technique, his mischievous tongue darting out to lick the ball, and the final Latin-tinged dance. A moment of pure, exaggerated performativity that bursts into the placid bowling routine, an explosion of sexuality and machismo that contrasts with and simultaneously complements The Dude's existential minimalism. The bowling alley itself becomes a microcosm of America, a stage for daily rituals and for the more or less sublime challenges of existence.

Another grandiose gag, and the quintessence of Coen-esque humor: The Dude and Walter surreally scatter the ashes of their recently deceased friend into the sea, with Walter, in an attempt to impose his personal interpretation of the last will, revealing himself, disaster after disaster, to be more inept than The Dude himself. A gust of wind and The Dude finds his face covered in the sacred remains as he rages against the stoic Walt, in a moment that perfectly embodies the existential chaos permeating the entire film, and the fatal collision between good intentions and utter, hilarious incompetence. The sequence is a compendium of black humor, slapstick, and melancholic reflection on death and friendship, sealing The Dude's identity not as a hero, but as the sole, authentic survivor of the world's delirium. A film that, years after its release, generated a veritable philosophy of life, "Dudeism," testifying to its lasting impact and surprising depth.

Main Actors

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...