The Bridge on the River Kwai

1957

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

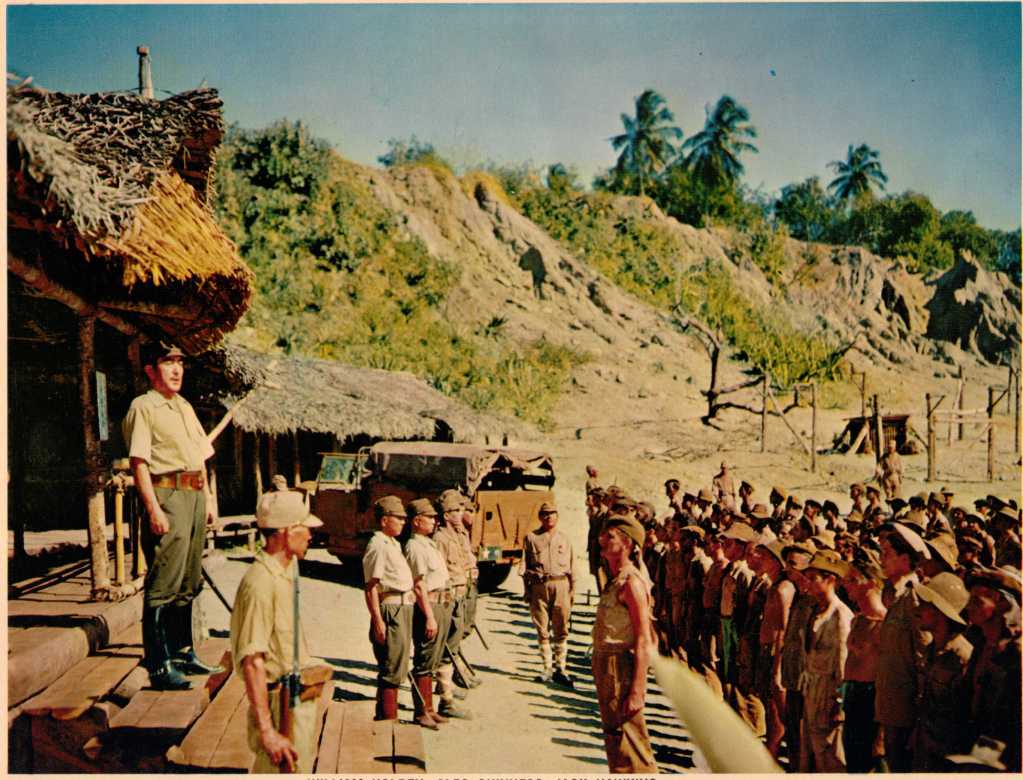

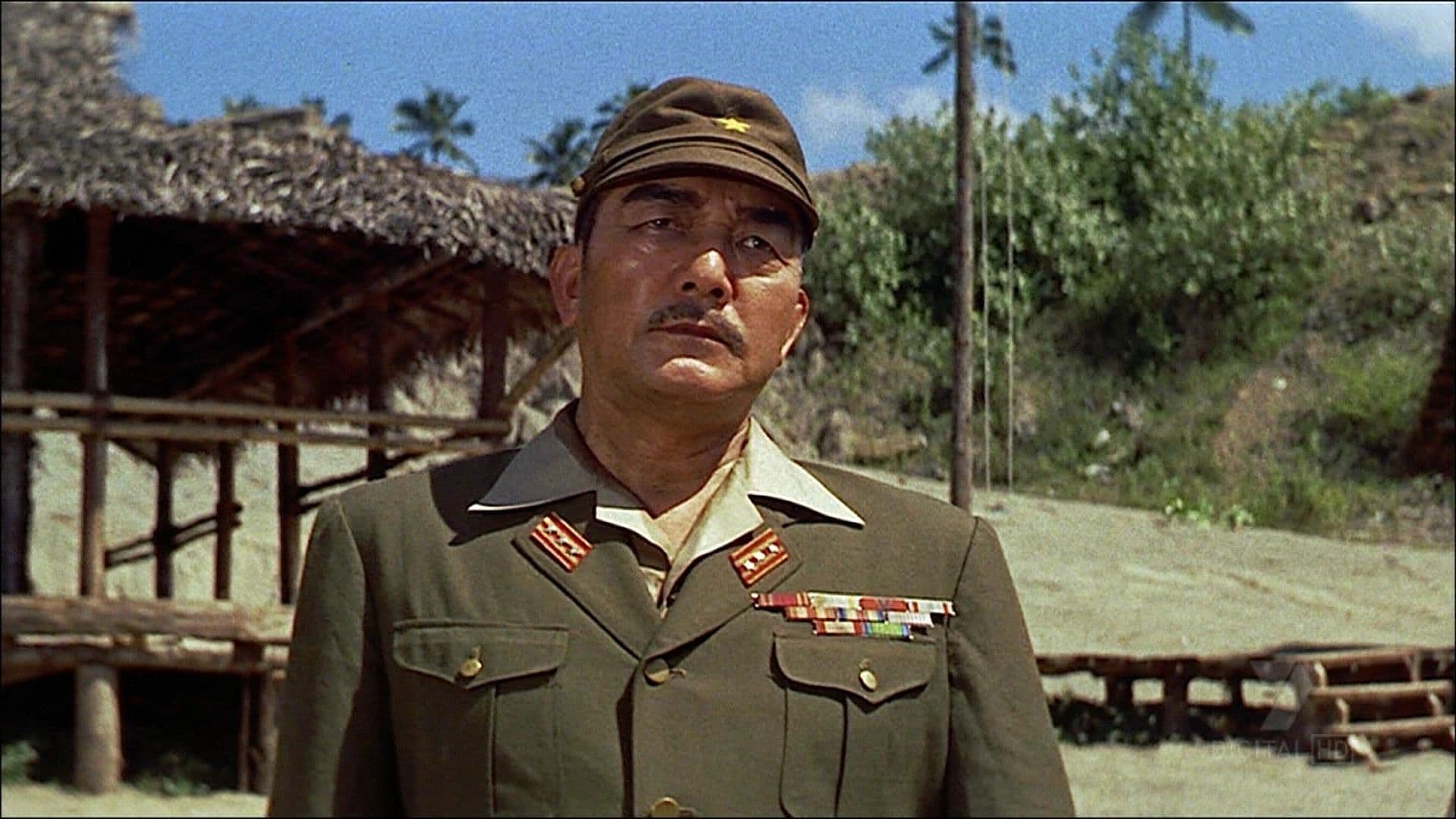

A story set in East Asia where a group of British prisoners, in the hands of the Japanese, must build a bridge for the Siam railway, an undertaking considered humiliating by their captors. Instead, it will be an opportunity to demonstrate the honour and value of His Majesty's soldiers, in a conflict that transcends mere imprisonment to become a clash of philosophies and military codes: the rigidly hierarchical and inflexible Japanese Bushido against the phlegmatic yet equally unyielding British "stiff upper lip." At the heart of this psychological and strategic conflict emerges the figure of Colonel Nicholson, masterfully played by Alec Guinness, whose obsession with regulations and military discipline drives him towards a paradoxical collaboration with the enemy, transforming the bridge's construction from an act of submission into an engineering masterpiece, a symbol of his culture's superiority (or perhaps folly).

David Lean, in his first major production, to be followed by many others – Lawrence of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago, and A Passage to India, to name a few – proves to be a filmmaker of great sensitivity, but above all an architect of visual narration, capable of combining the majesty of the epic with the intimate suffering of the individual. His meticulous and imposing direction leads the narrative to its climax (the explosion of the hated bridge), skillfully building suspense and emotional tension. The distant and menacing whistle of the approaching train, its increasingly near rattling, the anguished expressions of the military personnel involved in the plot, are a Rossinian crescendo worthy of the best Hitchcock, but amplified by the grandeur of the spaces and the gravity of the ethical and human implications. Lean does not merely tell a war story; he investigates the nature of discipline, the absurdity of misplaced honour, and the fragility of the human psyche under extreme pressure. The construction of the bridge is not just a physical act, but a metaphor for the construction and deconstruction of identities and values, with Colonel Nicholson, in an exemplary tragicomedy of obsession, unwittingly sabotaging his own ideals in the name of a perverse military perfection.

Jack Hildyard's cinematography, a trusted collaborator of Lean, is highly effective, here in his finest work. Hildyard masterfully captures the overwhelming vastness of the Asian jungle, the brutality of the prisoner-of-war camp, and, at the same time, the almost lyrical beauty of the imposing wooden structure rising from the Kwai waters. Every shot is a lesson in composition, where the equatorial light sculpts the drawn faces of the prisoners and imbues the landscape with an almost palpable presence, making it not just a backdrop, but a character in its own right that amplifies the human drama. His ability to transition seamlessly from breathtaking panoramas to intimate details elevates the film to a visual experience of rare power.

A film that, beyond conventional propaganda – although the theme of British heroism is evident, the psychological complexity of the characters elevates it far beyond simple glorification – remains a major milestone in cinematic history. Its subtle critique of the folly of war and rigid adherence to military principles, illustrated through Nicholson's character, is an element that distinguishes it and makes it eternally relevant. It is crucial to remember that the Oscar-winning screenplay was initially attributed to Pierre Boulle (author of the novel), but was in fact the work of Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, two writers blacklisted in Hollywood due to McCarthyism. This anecdote not only reveals the dark machinations of the film industry of those years, but adds another layer of irony and resilience to a work that, in every fibre, speaks of the struggle for freedom and integrity, even when the production reality denied it to its own creators. The story of the bridge over the River Kwai, though fictionalized, is inspired by the real horrors of the Thai Death Railway, an atrocity that cost the lives of thousands of Allied prisoners and Asian labourers, and the film, while not dwelling on the macabre, captures the essence of human suffering and resilience.

Also very famous is the soundtrack with the whistled tune of the "Colonel Bogey March," a pre-existing military march made iconic by the film. Its cheerful light-heartedness creates an unsettling counterpoint to the harsh reality of imprisonment and forced labour, becoming a powerful symbol of the invincible British spirit that defies oppression with a defiant grin and dignity. Malcolm Arnold's original score, also an Oscar winner, goes far beyond the famous theme, weaving a sonic tapestry that amplifies every moment of tension, every character's introspection, every grand panorama, contributing decisively to the work's emotional and dramatic impact.

A work of indisputable artistic merit where cinematography, screenplay, and actor direction make the difference, elevating The Bridge on the River Kwai from a mere war film to a profound reflection on the nature of honour, human folly, and the complexity of morality in times of conflict. Its influence is palpable in the epic and war genres, laying the groundwork for future explorations of the shadowed areas of heroism. Its ability to remain imprinted in collective memory is not solely due to its spectacular sequences or its famous melody, but to its courageous exploration of the contradictions that define the human being even when faced with the abyss of war and imprisonment.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...