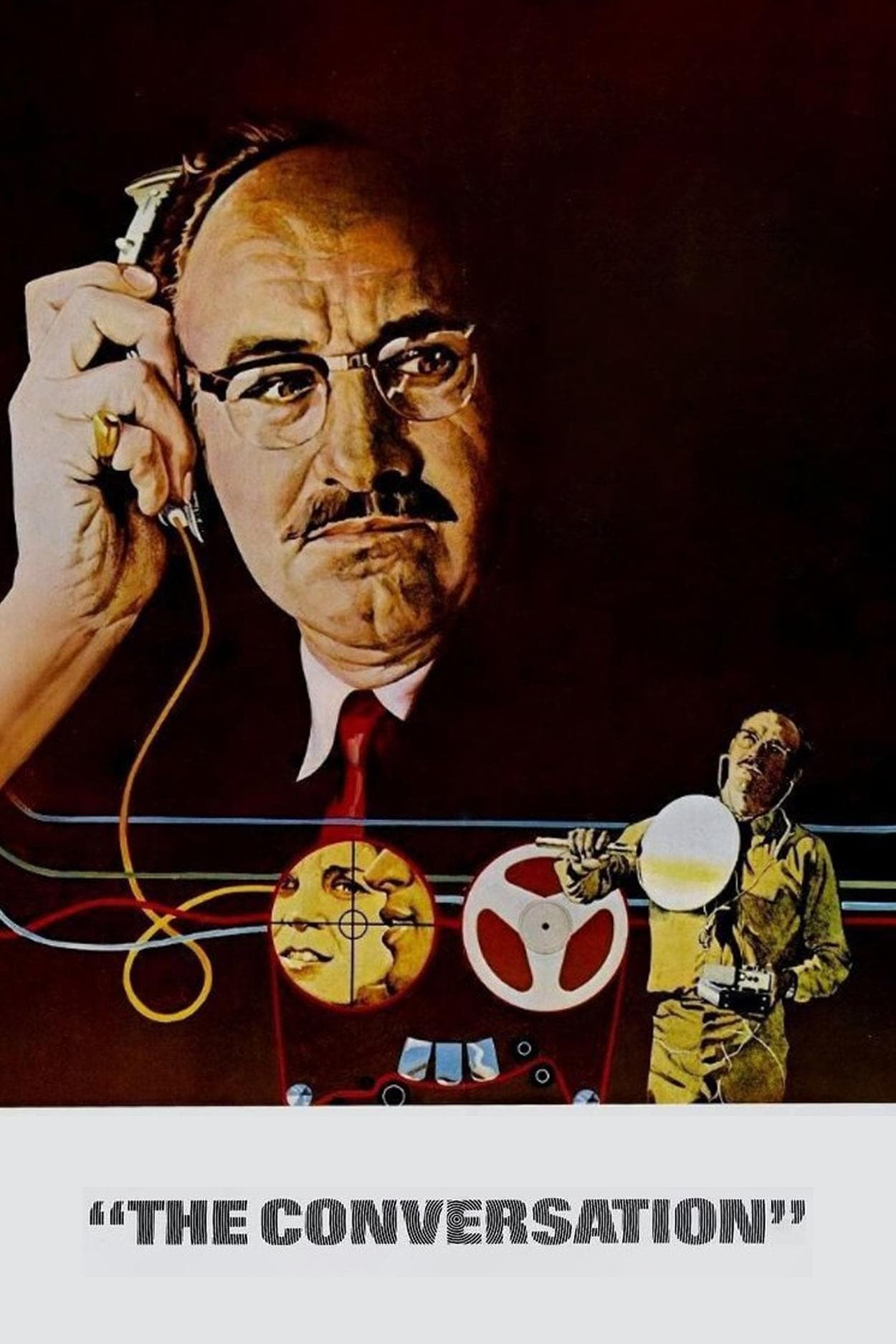

The Conversation

1974

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Francis Ford Coppola ventures into a spy story with a strong introspective and autumnal flavor. A work that, despite emerging between two giants of his filmography such as the first two chapters of The Godfather, demonstrates surprising authorial maturity and thematic depth, almost premonitory. It is not a simple thriller, but a lucid and chilling psychological study, a descent into the abyss of solitude and paranoia that resonates with the sinister echo of the Watergate scandal, contemporary to its release. It is a film that, at the heart of "New Hollywood," dares to slow down the pace, explore the cracks of the human soul, and question the nature of truth in an era of growing distrust.

Harry Caul is a paranoid genius of wiretapping, a meticulous craftsman of listening, whose expert hands manipulate tapes and frequencies with almost liturgical precision. His life is an hermetic sanctuary, protected by mental and physical barriers, a microcosm of solitude and ritual, punctuated by the sound of his saxophone, the only outlet for a tormented soul. He is given the seemingly routine task of wiretapping a young couple in a public square. But this will not be an investigation like any other.

Listening and relistening to the young couple's conversation – an ambiguous and elusive fragment of dialogue captured with sophisticated but imperfect tools – Harry becomes convinced that they are lovers and that the person who entrusted him with the job is the husband intending to kill them. Here begins Harry's true torture, a man who has erected a wall between his professional ethics and the moral consequences of his trade. Eaten by remorse over a previous job that ended in tragedy, he doesn't know how to warn the couple, but meanwhile discovers, with a destabilizing narrative twist that overturns his convictions, that it is the husband who has been killed by the couple. From that moment on, he will enter a spiral of revenge and blackmail that will make him paranoid, no longer a mere observer but a victim of his own profession. The film immerses us in his auditory obsession, making us re-listen to fragments, isolate words, perceive nuances, until the ambiguity of speech becomes a bottomless pit of interpretations, where every syllable can hide a deception or an unspeakable truth. The sound design, a masterful work by Walter Murch, thus becomes a co-protagonist, transforming background noise into a menacing chorus and vocal clarity into a source of anguish.

The final scene (the most beautiful in the film) sees him destroying all the furniture in his home, his last inviolable refuge, in search of non-existent bugs that might be spying on him, a nihilistic self-sabotage that reduces his world to a pile of rubble. It is the desperate act of a man who, having invaded the lives of others, now feels his own violated, trapped in an invisible cage of self-induced paranoia. He then sits melancholically on the rubble, playing his saxophone, the only voice left to him, a solitary lament emerging from the deafening silence of his destruction.

The perception of reality is distorted and the protagonist no longer knows what is real and what is not, a theme that Coppola investigates with an almost Orwellian sensibility. Despite all his technical expertise in wiretapping, which allows him to capture and analyze every minimal sound vibration, he feels irremediably lost because he is completely detached from the real fabric. His ability to decipher the sounds of the external world clashes with his inability to decipher his own psyche, leading him into ever deeper isolation.

Coppola's work closely resembles Antonioni's Blow Up, where a photographer experienced the same sensation through the sense of sight, with the frozen and seemingly revealing image proving enigmatic and mute, while here the sense of hearing is involved, with the same detachment from reality. Both films are masterpieces on the unreliability of perception and the existential solitude of the artist/technician, who attempts to grasp reality through a mechanical filter, only to find himself confronted with an incomprehensible void. If Antonioni depicted the visual alienation of Swinging London, Coppola immerses us in the deafening echo of American paranoia, an invisible disquiet that devours trust and annihilates all certainty. To this diptych one could ideally add Brian De Palma's Blow Out (1981), which completes the triptych with a sound engineer as protagonist, taking the theme of sound manipulation to new, terrifying conclusions and creating a fascinating cinematic thread on the relationship between sensory perception, technology, and truth.

The Conversation is also a detailed reflection on the role of the overheard word, on the noise of the world around us, and on how to interpret it. It is not only what is said, but how it is said, and especially how it is heard and reinterpreted, that shapes our reality. It is a keen investigation into privacy and surveillance, themes that, almost fifty years after its release, are more relevant than ever in an age of mass surveillance and "big data."

A great Gene Hackman in the role of a character who appears utterly authentic in his neuroses and, above all, in his most intimate weaknesses. His performance is a masterpiece of subtlety, where every tic, every fleeting glance, every minimal gesture communicates a devastating inner turmoil. He is not the charismatic hero of other roles, but a fragile anti-hero, whose vulnerability makes him terribly human. Hackman masterfully embodies the silent anguish of a man trapped not only by his profession but by his own conscience, making Harry Caul an icon of American paranoid cinema. His performance is a silent cry for help that echoes far beyond the last, chilling shot.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...