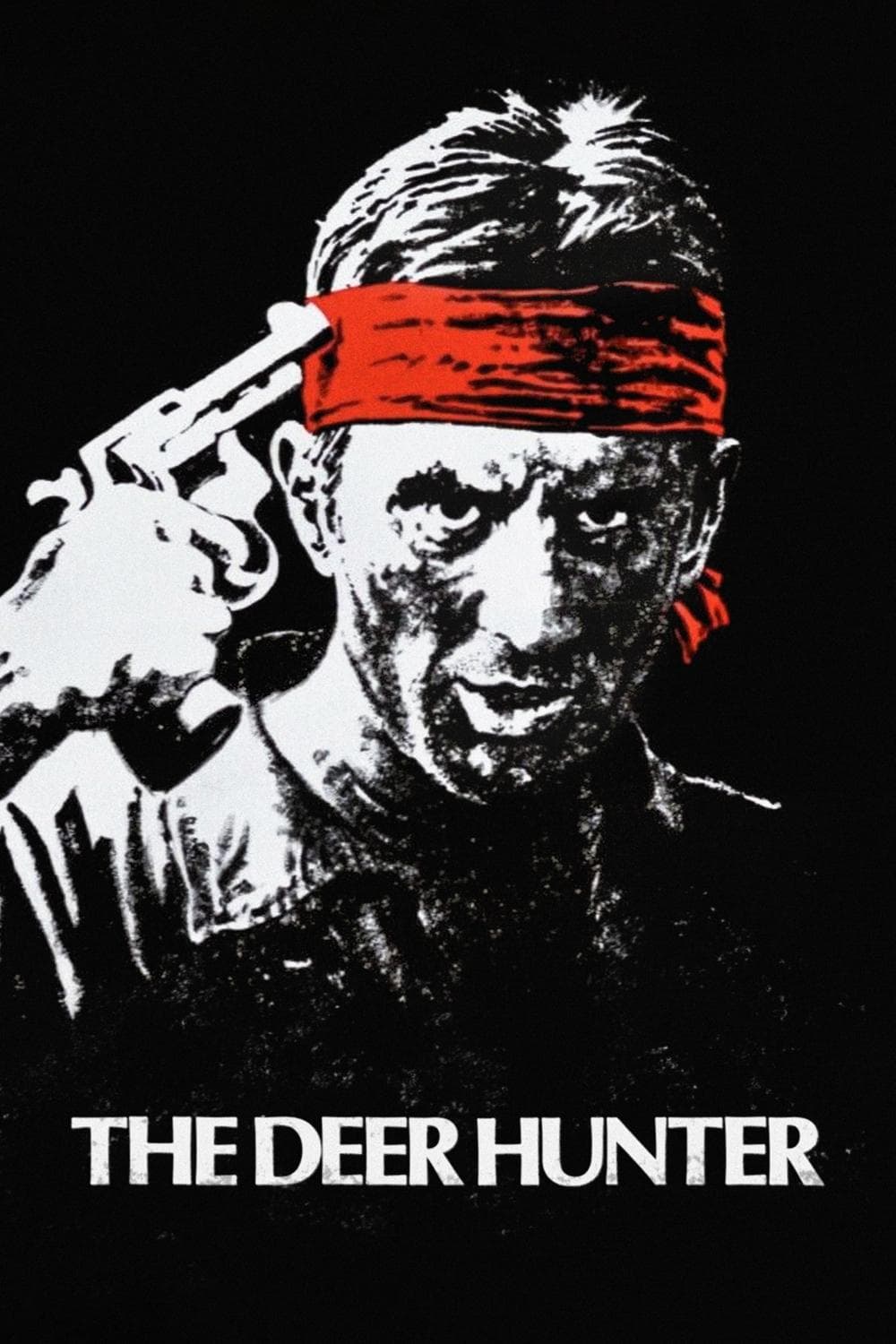

The Deer Hunter

1978

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

War digs deep into people and transforms them into something different, alien, unknowable. Not merely an external change, but a corrosion of the very essence, an erosion of the foundational pillars of identity that define us. It is the profound resonance of this proposition that pulsates at the heart of "The Deer Hunter," Michael Cimino's epic and poignant masterpiece, which with an almost brutal clarity probes its intrinsic value within American society in the post-Vietnam era. Far from triumphalist narratives or overtly political denunciations, Cimino opts for an immersion into the wounded soul of a nation, filtered through the broken lives of common men.

The film initially introduces us to an almost idyllic provincial tableau, in the small and industrious industrial town of Clairton, Pennsylvania. Here, three friends, Michael, Nick, and Steven, live an existence marked by daily routine, work in the steel mill, and the social rituals that cement the community: boisterous weddings, evenings at the bar, the sacred and ritualistic deer hunt in the mountains. These initial sequences, dominated by a lyrical naturalism and warm, enveloping cinematography by Vilmos Zsigmond, are fundamental. They are not mere introduction, but the embodiment of pre-war innocence, an American Eden destined to be irretrievably shattered. The deer hunt, in particular, with Michael's "one shot" philosophy (portrayed by a Robert De Niro of titanic intensity), proves to be a powerful metaphor for life itself: concentration, precision, the ability to hit the mark without waste, an ideal of control and purity that war will sweep away with unprecedented violence.

When these men are torn from this reassuring routine to go fight in Vietnam, the impact is disorienting, almost surreal. The transition from the festive wedding to the hell of Vietcong captivity is one of the most shocking and abrupt ellipses in cinema history, catapulting the viewer into an abyss of barbarity. Two of them, Michael and Steven, return from that hell in critical condition: Michael, though physically intact, is alienated, his spirit weakened and his worldview irretrievably altered; Steven, on the other hand, is physically annihilated, confined to a wheelchair and with even deeper invisible scars. The third of them, Nick, does not return, or rather, remains trapped there, lost in a kind of self-degradation and madness after suffering physical and psychological tortures so savage that his identity was shattered. Christopher Walken's performance, for which he won an Oscar, is a chilling portrayal of this descent into the abysses of the human psyche.

The film, with an almost operatic structure, continues with Michael who, unable to accept the loss, decides to return to Vietnam to retrieve Nick. This is not a simple rescue mission, but a Dantesque odyssey through the circles of post-war despair, a desperate attempt to mend the tattered fragments of a friendship and, metaphorically, to recompose his own fragmented soul and that of a nation. When he encounters him, Michael finds himself faced not with the friend he remembered, but with an unknown person, an empty shell devoid of all essence, a ghost spending his nights in Saigon, a feverish and chaotic post-war Saigon, playing Russian Roulette for money, in a self-destructive cycle that is simultaneously a metaphor for war itself and for the absurdity of a purposeless existence.

This journey into despair, into psychological decay, elevates "The Deer Hunter" to a work of absolute significance, a visceral manifesto against all war, not through pacifist rhetoric but by showing the irreparable destruction of the individual. The Russian Roulette sequences, which have become iconic, are the emotional and conceptual core of the film: the first, in the fetid hut of the captors, is an exhibition of pure terror and humiliation, an imposed deadly game that strips men of their dignity; the second, the final one where Michael and Nick dramatically face each other in a smoky and decadent venue, is the culmination of the tragedy. Here, Michael attempts in every way to tear Nick away from his self-destructive fate, even at the cost of his own life, in a duel that is simultaneously physical, psychological, and spiritual, but whose outcome, due to the indelible horror rooted in Nick's soul, is tragically inevitable.

The work is dramatic and unsettling, and its release was accompanied by harsh criticism, particularly at the Berlin Film Festival, where left-wing groups did not forgive Cimino for portraying the Vietcong as sadistic tormentors, accusing him of a biased and anti-communist representation. However, reading "The Deer Hunter" through the lens of mere historical accuracy is reductive and mystifies its true strength. The film's main interpretative key, in fact, does not lie in a geopolitical analysis of the conflict, but rather in the devastating effect of war on the soldiers who fight it, their irreversible descent into the labyrinths of their personal horrors, a trauma that transcends all factions. Cimino does not intend to offer a political judgment, but rather to probe the nature of the psychological wound that war inflicts, a wound that knows no flags. The film is a profound exploration of the human psyche under extreme pressure, of the loss of innocence and the difficulty, if not impossibility, of returning to normality after looking into the abyss. It is a cinematic monument to resilience and, at the same time, to the fragility of the human soul in the face of unspeakable horror. Its influence has been enormous, defining for years how American cinema would address the trauma of Vietnam and solidifying Cimino's reputation as an auteur with a grandiose, albeit controversial, vision.

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...