The Graduate

1967

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Benjamin Braddock is returning home after graduating. His face is apathetic, distant, inert as the plane lands. It is not the joy of achievement that marks his features, but rather an existential vertigo foreshadowing the bourgeois purgatory into which he is about to plunge. It is the face of a generation, one that approaches the Sixties not with the unbridled optimism of the Baby Boomers, but with a sense of emptiness, unexhausted waiting, and profound estrangement from a world his parents built and in which he feels imprisoned. This post-university anomie, sublimely captured in the first frame, immediately manifests itself upon his re-entry into the social fabric: his parents, friends, old life – all coordinates that Ben perceives as a gilded cage, a pre-written and suffocating future that the famous word "plastics" – that enigmatic yet incredibly revealing warning about his presumed career – encapsulates with chilling precision.

It is precisely at the welcome-home party organized by his parents that young Braddock meets Mrs. Robinson, the wife of his father's business partner. A kind of love affair will begin with the woman, a clandestine relationship where, on one side, her bored cynicism is prominent, and on the other, his anxieties and uncertainties. Her cynicism is not mere coldness, but the glossy patina of an imprisoned soul, of dormant desires and a rebellion never fully consumed, reduced to sensual calculation. Anne Bancroft imbues the character with an almost sculptural gravitas, transforming Mrs. Robinson from an archetypal predator into a tragic figure, a mirror of an affluent but spiritually barren America, a woman perhaps as much a victim as an executioner of a system of conventions. A dualism, that between her world-weary experience and his awkward innocence, that contrasts and interpenetrates the two lovers, in an eternal interplay of passion and hesitation, seduction and reticence, where desire merges with shame and liberation with imprisonment.

Love for Mrs. Robinson's daughter, Elaine, seems to be able to save Ben from emotional drift, offering a glimmer of authenticity, a way out of the murky affair with her mother. But when the forbidden relationship with the mother emerges, Elaine's idealism clashes with harsh reality, and she rejects him, determined to marry another man, the good and predictable Carl Smith.

Mike Nichols directs, unearthing the roots of human passions and the terrible consequences of forbidden love with a mastery that transcends mere storytelling. Nichols is not interested in a moral dimension of the story, nor in the explicit social critique it carries. His lens is more surgical, more introspective. Nichols is interested in narrating the events by highlighting, through Ben's contradictions, the difficulties of a young man adapting to social conventions, of finding a sense of self in a world that offers him only predetermined roles and material well-being devoid of vitality. The primordial material that emerges and indeed forms the core of the work is the almost veristic account of a love censored by social conventions and bourgeois respectability, all without any Manichaean judgment.

It is no coincidence that this film emerged precisely at the dawn of New Hollywood, a movement that would deconstruct conventional narratives, embrace moral ambiguity, and lay bare the cracks in the American dream. Robert Surtees' cinematography, with its sometimes claustrophobic close-ups and shots that isolate Benjamin in the vastness of empty spaces, or trap him among the architects of his own imprisonment (his parents, the aquarium, even the hotel room that becomes both a refuge and an emotional prison), amplifies the sense of alienation and the search for authentic identity in a world that seems to offer only "plastics." The soundtrack, a true resonance chamber for Benjamin's soul, is a masterpiece in itself, with Simon & Garfunkel's songs not merely commenting on the action but becoming the protagonist's inner voice, a modern Greek chorus whispering his anxieties, hopes, and despair. Tracks like "The Sound of Silence" and "Mrs. Robinson" are not just hits, but narrative cornerstones that lend the film an unprecedented emotional and generational resonance.

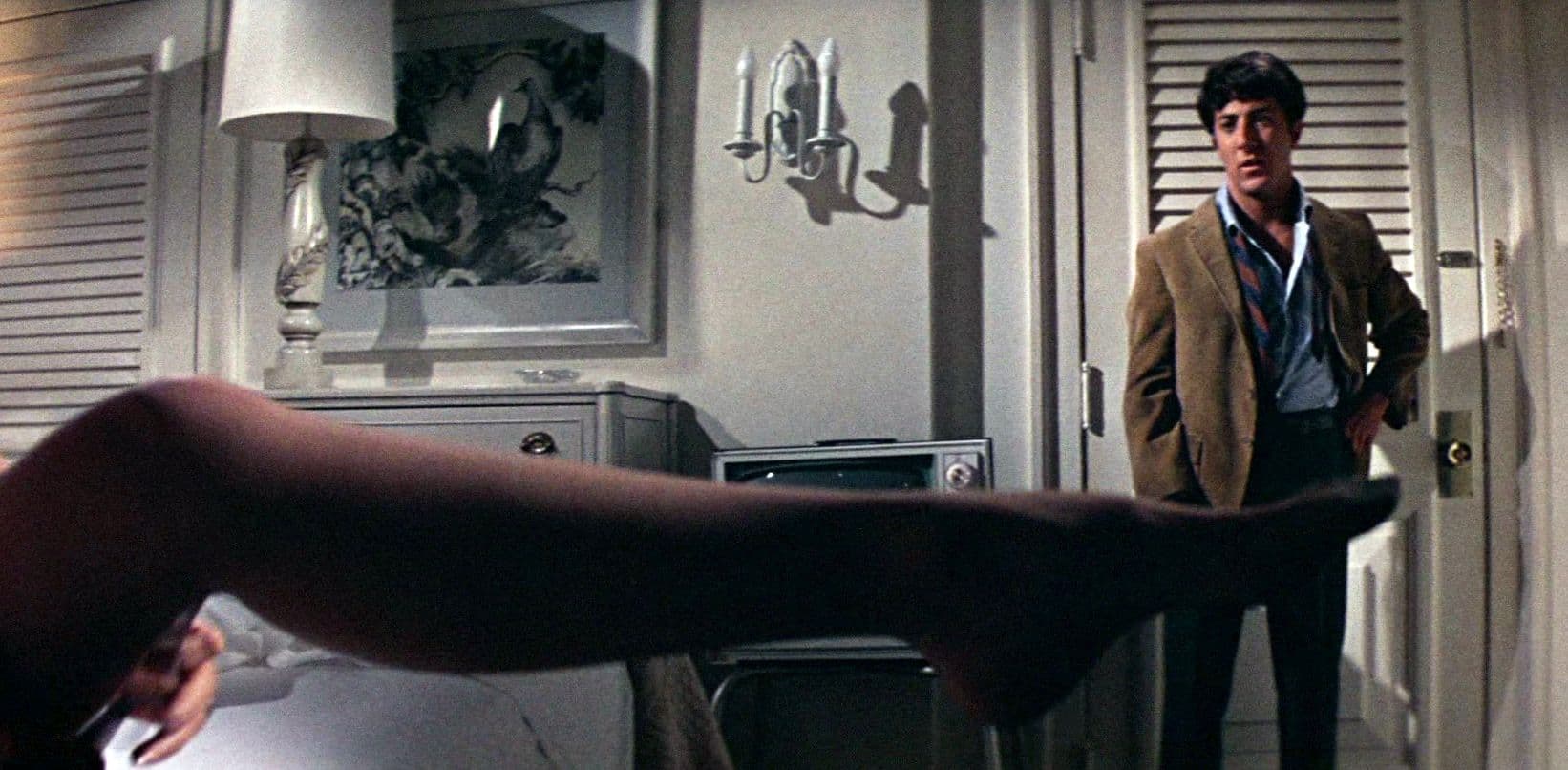

One memorable scene above all others: the kiss between Ben and Mrs. Robinson and her glacial undressing. The sequence is a microcosm of their entire relationship: Mrs. Robinson, with calculated meticulousness, asks for a hanger to carefully put away her leopard fur coat – a symbol of predatory elegance and now empty luxury – and takes the time to remove a stain from her blouse. Ben, on the sidelines, is consumed by anxiety and shame, paralyzed by youthful awkwardness in the face of such a ruthlessly efficient seduction. It is a choreography of power and concealed desire, of control and impotence, that unfolds in the charged silence of an anonymous hotel, away from prying eyes, but which at the same time traps them both in a game without winners. The sequence anticipates the ambiguity of the ending: Ben and Elaine's liberating escape on the bus, though seemingly a triumph, dissolves their smiles into an expression of perplexity, weariness, perhaps terror for a future that, outside of overturned conventions, is an unknown land, as much a precipice as Mrs. Robinson's bed. A masterpiece that continues to question the aspirations and disappointments of every generation.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...