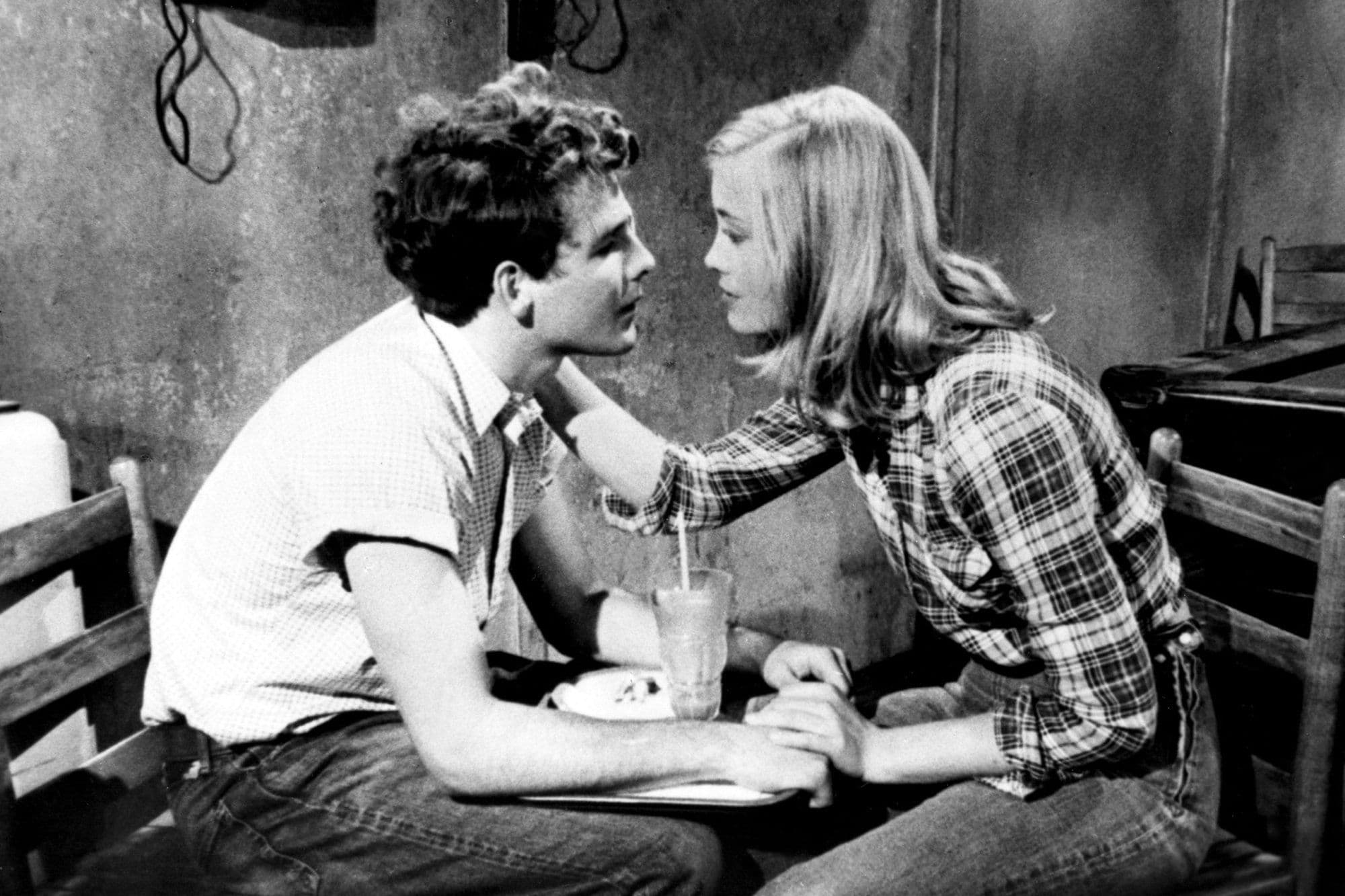

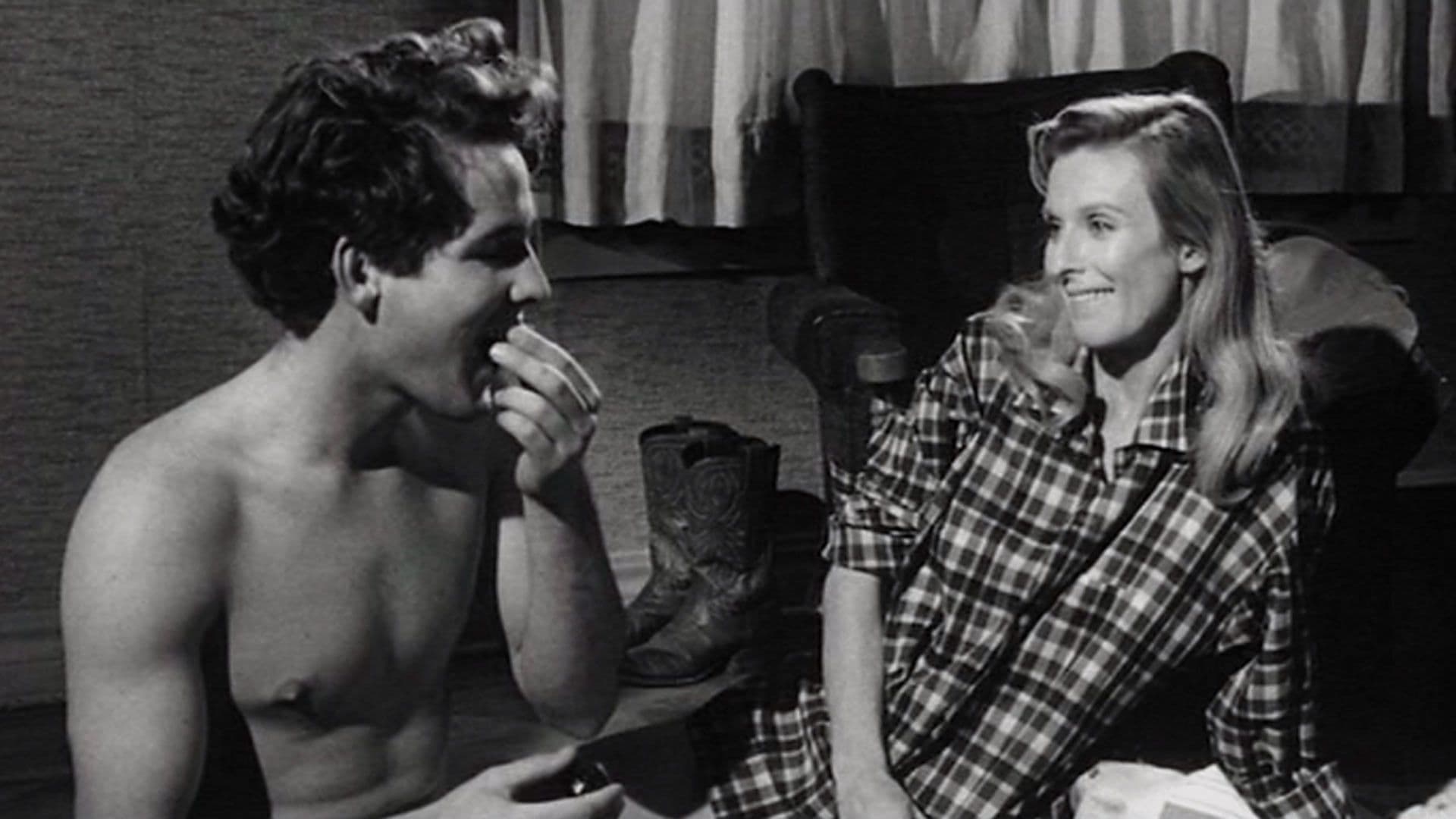

The Last Picture Show

1971

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Bogdanovich transcends (finally, one might say) the Hollywoodian "problem-solution-happy ending" syllogism to narrate a story of moral, psychological, and economic distress. In an era when "New Hollywood" was beginning to deconstruct established narrative frameworks, The Last Picture Show stands as a milestone, marking an acute examination of the American soul far beyond reassuring patterns. Orson Welles’s favorite pupil, a cinephile critic dedicated to the rediscovery of classical masters, here demonstrates surprising authorial maturity, not disavowing the deep roots of American cinema – one thinks of the crystalline purity of the shots, an unconcealed homage to John Ford or Howard Hawks – but reinterpreting them through a lens of twilight melancholy and existential disillusionment. It is a film that positions itself on the threshold, an announced epilogue of lost innocence, a funeral dirge for a rural America crumbling under the weight of its own inertia and unkept promises.

A slow disintegration of every value, where decadence itself is the object of an unflinching dissection and ascends to the semantic core of the message. It is not only the moral decline of its inhabitants that is placed under the magnifying glass, but rather a broader fresco of a provincial America that crumbles, devoid of horizons and hope. The closure of the town’s only cinema, an apparently marginal event, becomes a poignant metaphor: not only does the projector's light go out, but also the last spark of a collective illusion, the capacity to dream, to escape from mundane reality. It is the twilight of an era, a slow and inexorable descent into an abyss of solitude and aimlessness, a visual and sonic lament that echoes post-war disillusionment, the long shadow of an "American dream" that reveals itself to be a mirage in the Texan desert.

The story is set in a remote Texas town in the early 1950s. This choice of setting is not casual, but deeply imbued with the rough and melancholic realism typical of writer Larry McMurtry, author of the novel from which the film is adapted. Archer City, the real name of the place where Bogdanovich chose to film, becomes the archetypal topos of the American province in decline, a black and white universe that, far from being a mere stylistic choice to evoke the era, is the visual translation of a state of mind, an existential greyness that negates the color of hope. Cinematographer Robert Surtees masterfully paints an arid emotional landscape, where the wind blows through dusty streets and souls wander aimlessly, prisoners of a cycle of dissatisfaction and futile anticipation. The camera becomes a disenchanted, almost anthropological eye, investigating the desolation of a world that has ceased to evolve.

Sonny is a man overwhelmed by events, trying to survive the boredom of provincial life. His figure is not that of the classical hero, but rather a passive anti-hero, an aimless Ulysses wandering in his own inner labyrinth. His is an existential journey through the ruins of a disappearing world, an echo of the desolate figures that populate Italian Neorealist cinema or the French Nouvelle Vague, but here situated in the heart of an American province that seethes with repressed frustrations. Sonny embodies lost youth, the inability to grasp a future when the present is a quagmire and the past a faded memory.

He will take over a local cinema with varying fortunes, move from one disillusioned lover to another, and cultivate a unilateral friendship with a young man with an intellectual disability. Each of these relationships is a narrative shard that illuminates the futility of Sonny's attempt to escape his condition. The cinema, more than an activity, is a wreck, a graveyard of broken dreams. His emotional relationships, from the sophisticated and fragile Ruth Popper – portrayed with a moving dignity by Cloris Leachman, which earned her an Oscar – to the spoiled and superficial Jacy Farrow, reveal a widespread emotional ineptitude. With Ruth, Sonny seeks a surrogate for maturity, an embrace in an equally wounded soul, but their bond is destined to languish, a mere momentary antidote to loneliness. With Jacy, daughter of the local bourgeoisie and a symbol of empty ambition, the illusion of a possible escape, of a novelistic love, is played out, revealing itself to be nothing more than a perverse and narcissistic performance. And then there is Billy, the boy with cognitive deficits, a pure of heart whose innocent existence and tragic fate (an event that moves without sentimentality, but with the stark cruelty of destiny) serve as a catalyst, shaking Sonny from his torpor and revealing the intrinsic brutality of an environment incapable of protecting fragility. Billy, the last eidolon of unspoiled genuineness, is sacrificed on the altar of a cynical and indifferent world, making palpable the silent violence of the province.

Behind Sonny, we glimpse Bogdanovich’s restless and acute shadow, pushing his directorial talent to portray the very essence of the restless spirit that animates his anti-hero, stripping him bare and finally glorifying him with ill-concealed irony. It is not disdainful irony, but humor imbued with an almost painful empathy, the acute awareness that in this gallery of defeated and unresolved characters resides a universal truth about the human condition. The film is a visual epitaph, a whispered funeral hymn that, far from being didactic, settles into the viewer's soul, leaving a persistent echo of desolation and beauty. It is the melancholy of an auteur who looks at his characters with a sorrowful affection, a father watching his children grow in a world without hope, but nevertheless finds, in their stubborn and vain struggle for a glimmer of happiness, a form of silent and touching grandeur.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...