The Manchurian Candidate

1962

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Another example of a film marred by a shoddy Italian title that effectively transforms it into a cheap whodunit. "Go and Kill" sounds like a bargain-bin b-movie, whereas the original title, The Manchurian Candidate, immediately evokes a far more sinister and resonant echo, projecting the viewer into the chilling heart of the era's geopolitical paranoia. It is no coincidence that "Manchurian" later entered common parlance to define an hypnotized individual, a puppet without a will of their own, a perfect vehicle for an obscure and invisible evil.

Instead, it is a great film, where political scenarios and psychological microcosms intersect to create a taut and intelligent thriller that transcends mere suspense to delve into the murky waters of the psyche and ideological manipulation. Based on Richard Condon's The Manchurian Candidate, the film tells the story of a Korean War veteran, Sergeant Raymond Shaw, who returns home after undergoing mental conditioning and insidious programming by the communist regime of that country, in a secret clinic that blends Pavlovian techniques with an almost Orwellian distortion of reality. His covert mission will be to carry out a political assassination aimed at subverting the country from within, a threat infinitely more insidious than any external force.

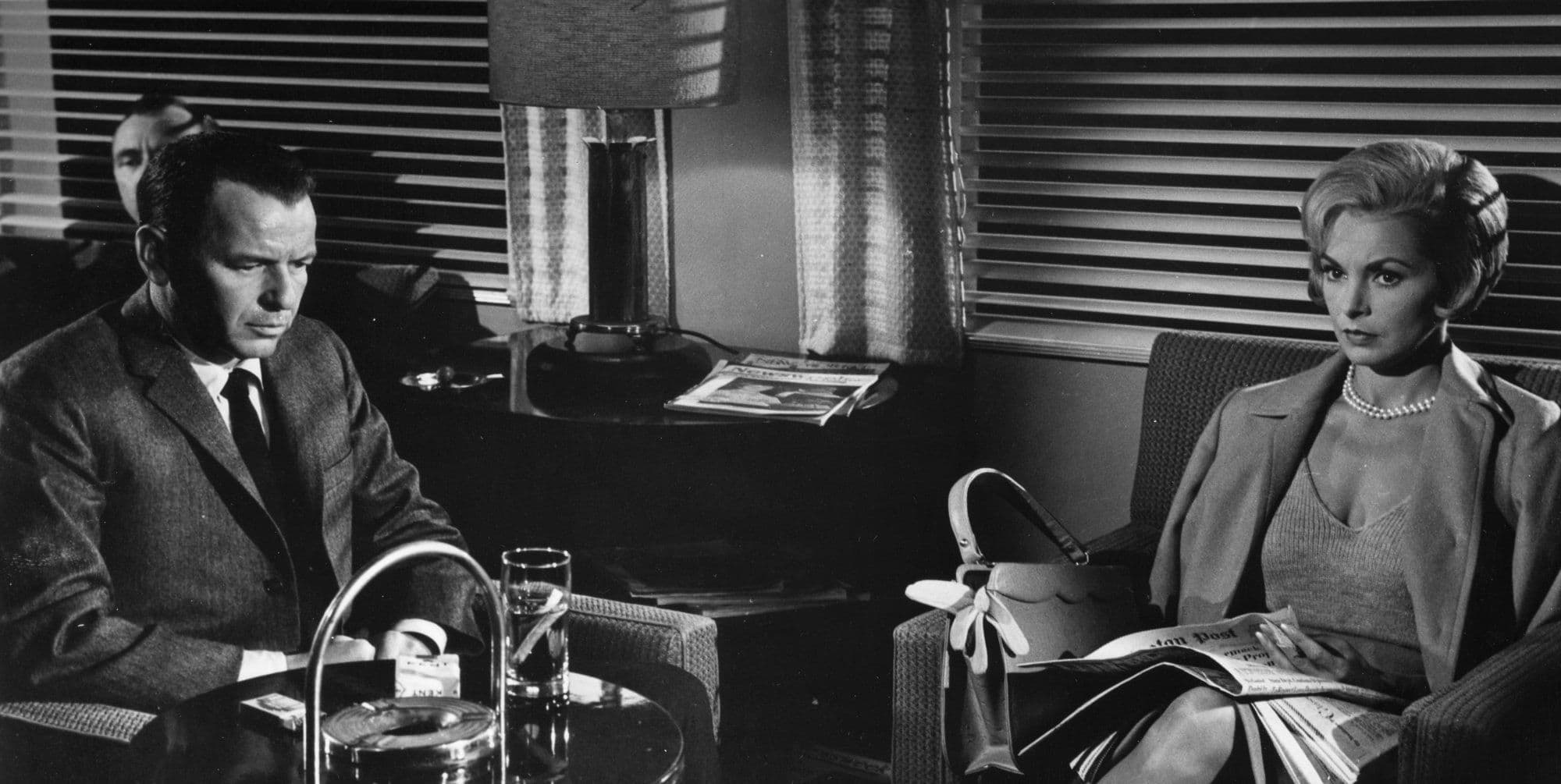

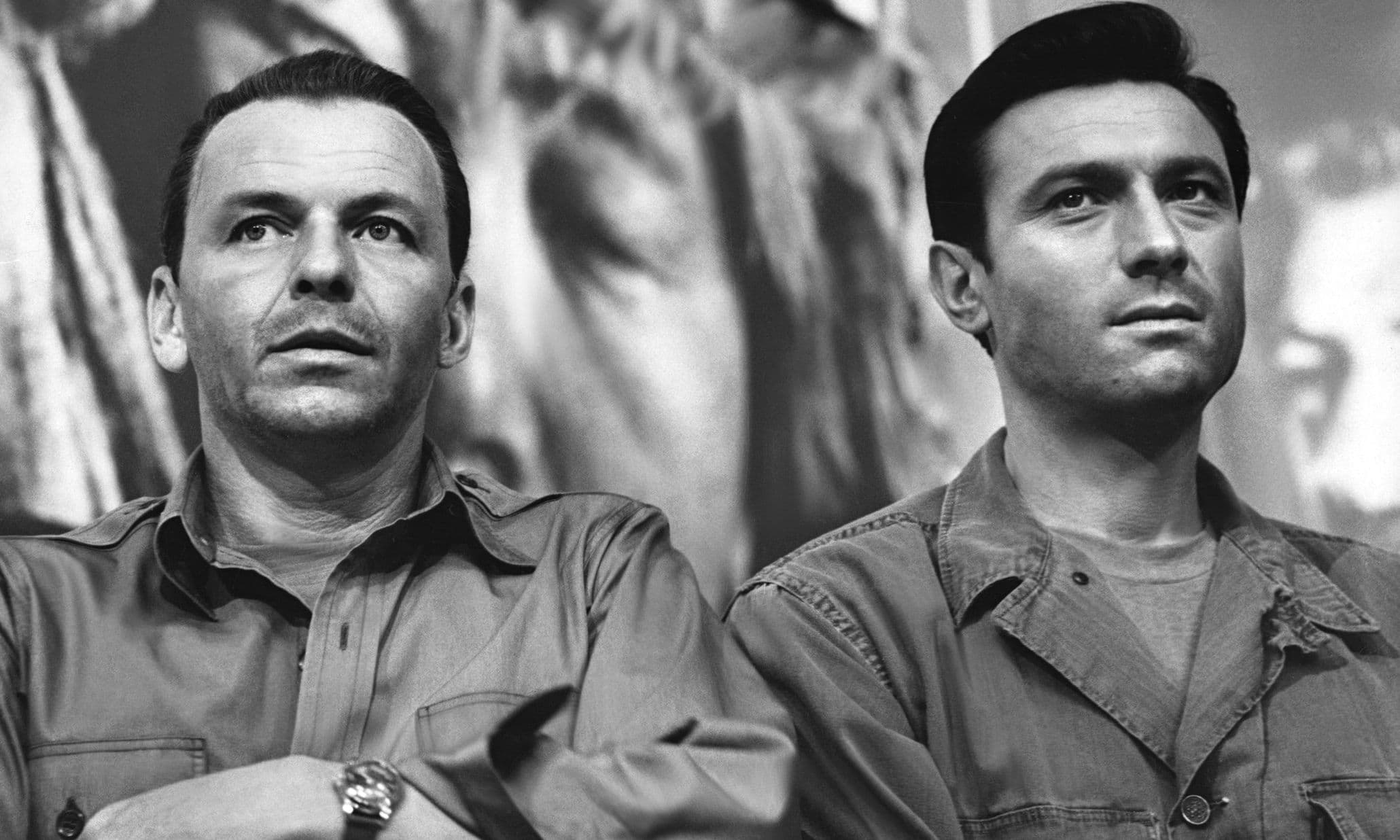

Another prisoner of war, Major Bennett Marco (portrayed with his usual intensity by Frank Sinatra, in one of his most complex and nuanced acting performances), tormented by recurring nightmares and a growing sense of falsity in his memories, helps to hunt him down and unearth him, in an odyssey that will lead him to doubt his own sanity and the loyalty of anyone. The dramatic work accomplished with consummate skill by George Axelrod in adapting the novel for the big screen is simply exceptional. Thanks to his work, the film retains that atmosphere of psychodrama and paranoid nightmare that constitutes its deepest essence, amplifying the dystopian dimension of the novel and transforming it into a visceral and intellectually stimulating experience. Axelrod does not merely transpose the plot but infuses the screenplay with caustic wit and satirical venom that lash political demagoguery and bourgeois conformity, making the film a surprisingly sharp commentary on the fragility of American democracy.

The viewer is led by the hand through the mysteries of the human mind and how it can be warped by malevolent reprogramming, such as to potentially turn anyone, even the most decorated war hero, into a ruthless enemy. It is a chilling reflection on the loss of identity, the violation of individual will, and the possibility that the most dangerous enemy is not behind the Iron Curtain, but can lurk in the very heart of society, camouflaged behind a reassuring smile or a badge of honor. This theme of "programming" and mind control has permeated not only the thriller genre but has echoed throughout popular culture, influencing subsequent works from cyberpunk to science fiction, and even to the most experimental art-house cinema.

John Frankenheimer's direction is a masterpiece of tension and disorientation. The way he articulates the dream and flashback sequences, alternating perspectives and distorting the perception of reality, is masterful. The conditioning scenes, in particular, with their tight editing and angled shots, immerse the viewer in a sensory labyrinth of terror and confusion, evoking the schizophrenia of Shaw's psyche and the manipulation he undergoes. Frankenheimer, already a master in the psychological thriller genre (consider Seven Days in May or Grand Prix, where the mental pressure is palpable), here reaches unparalleled heights of mental claustrophobia, exacerbating the sense of a conspiracy as vast as it is incomprehensible.

The film ignited strong controversy for its political vision in which Americans are not necessarily the good guys, but victims, perpetrators, and puppets in a power game far more cynical than Cold War rhetoric would admit. The figure of the matriarch and manipulator, Mrs. Iselin, played by an icy and unsettling Angela Lansbury (who earned an Oscar nomination for this iconic performance), is the linchpin of this moral ambiguity. She embodies a form of hysterical and opportunistic patriotism that does not hesitate to exploit her own son for thirst for power, revealing an internal threat more insidious than any foreign agent. Her perfidy, her subtle but relentless cruelty, elevates the film from a simple thriller to an unsettling exploration of the corruption of the soul and the perverse intertwining of politics and family.

Distributed in 1962, at the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis and still palpable McCarthyism, "Go and Kill" was perceived by many as excessively audacious, if not outright seditious, for its portrayal of a conspiracy so deeply rooted in the very fabric of America, involving prominent figures and questioning the purity of the American ideal. The urban legend, later partly disproven but persistent, that the film was pulled from circulation after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, just one year after its release, due to its disconcerting and traumatic resonance with real events, contributed to augmenting its myth and its aura as a "cursed" and prophetic work. It is a testament to its ability to strike raw nerves and anticipate the anxieties and conspiracies that would later mark the subsequent years. And for this reason alone, for its prophetic audacity, for its acute analysis of the pathologies of power and the human psyche, it should be seen and appreciated as a timeless classic of art-house cinema and the political thriller.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...