The Royal Tenenbaums

2001

Rate this movie

Average: 4.50 / 5

(2 votes)

Director

An eccentric family where each character parades their own ironic madness. This eccentricity, however, is never an end in itself, but delves into the depths of an existential unease that Wes Anderson, with his unmistakable lens, renders universal and strangely recognizable.

Wes Anderson gives us a treasure chest where life runs in reverse and where every gesture defines a precise family lexicon of which we would like to be a part. But it is a lexicon also imbued with unspoken words, unhealed wounds, and a chronic inability to communicate openly, concealed behind layers of bizarreness and detachment. The director succeeds in a rare feat: making us perceive the profound melancholy that lurks beneath the surface of every visual gag and every witty remark, creating a precarious balance between laughter and sigh, between tenderness and the bitter awareness of lost opportunities.

Each family member is a small microcosm with its own laws and occurrences. These isolated universes, though seemingly self-sufficient, are in reality deeply interconnected, united by invisible threads of twisted affection and shattered expectations.

The collision of these wandering monads will form the main backbone of the work and its unparalleled seduction towards the sophisticated and ever-demanding viewer. It is in the friction between the manic order of the shots and the emotional chaos of the characters that Anderson's true magic is unleashed, a dialectic that elevates the film beyond a simple family comedy to approach a visual essay on the fragility of the human condition and the overwhelming burden of a past as glorious as it is cumbersome.

The Tenenbaum spouses, he a lawyer, she an archaeologist, have three young children, each endowed with their own peculiar talent: Margot, adopted, is an accomplished playwright who, at nine years old, wins a thousand-dollar prize; Chas at 12 is already a financial genius, and Richie is a world-renowned young tennis champion. The imprint of these precocious successes, almost a burden, insinuates itself into their adult lives, defining them and, at the same time, suffocating them.

The family, as time passes, falls into decline: the two parents separate, while the children seem to squander their talent in adulthood, crushed by the weight of expectations and disillusionment. It is not just a loss of ability, but a genuine identity crisis, an implosion of their childlike archetypes into adult figures marked by uncertainty.

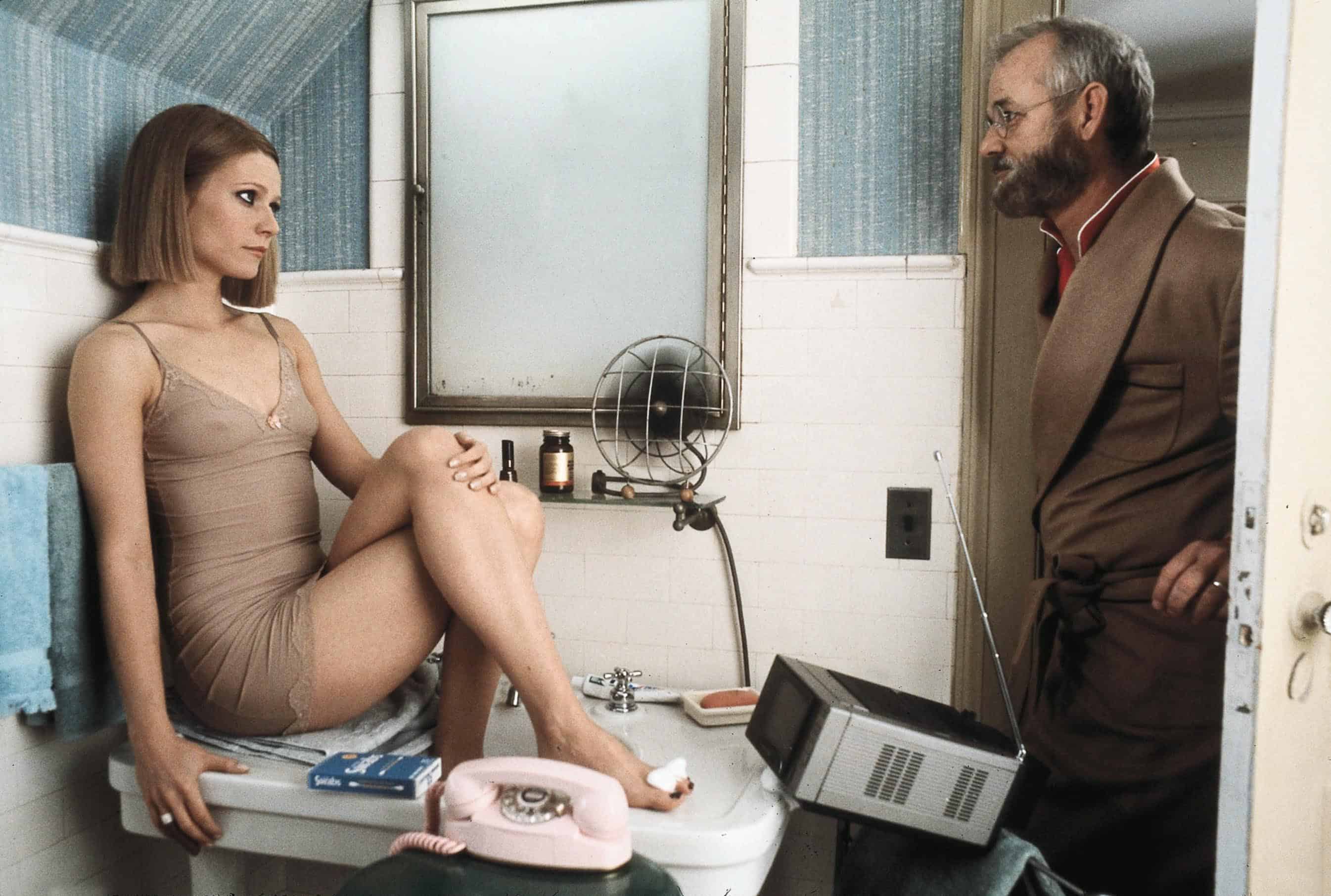

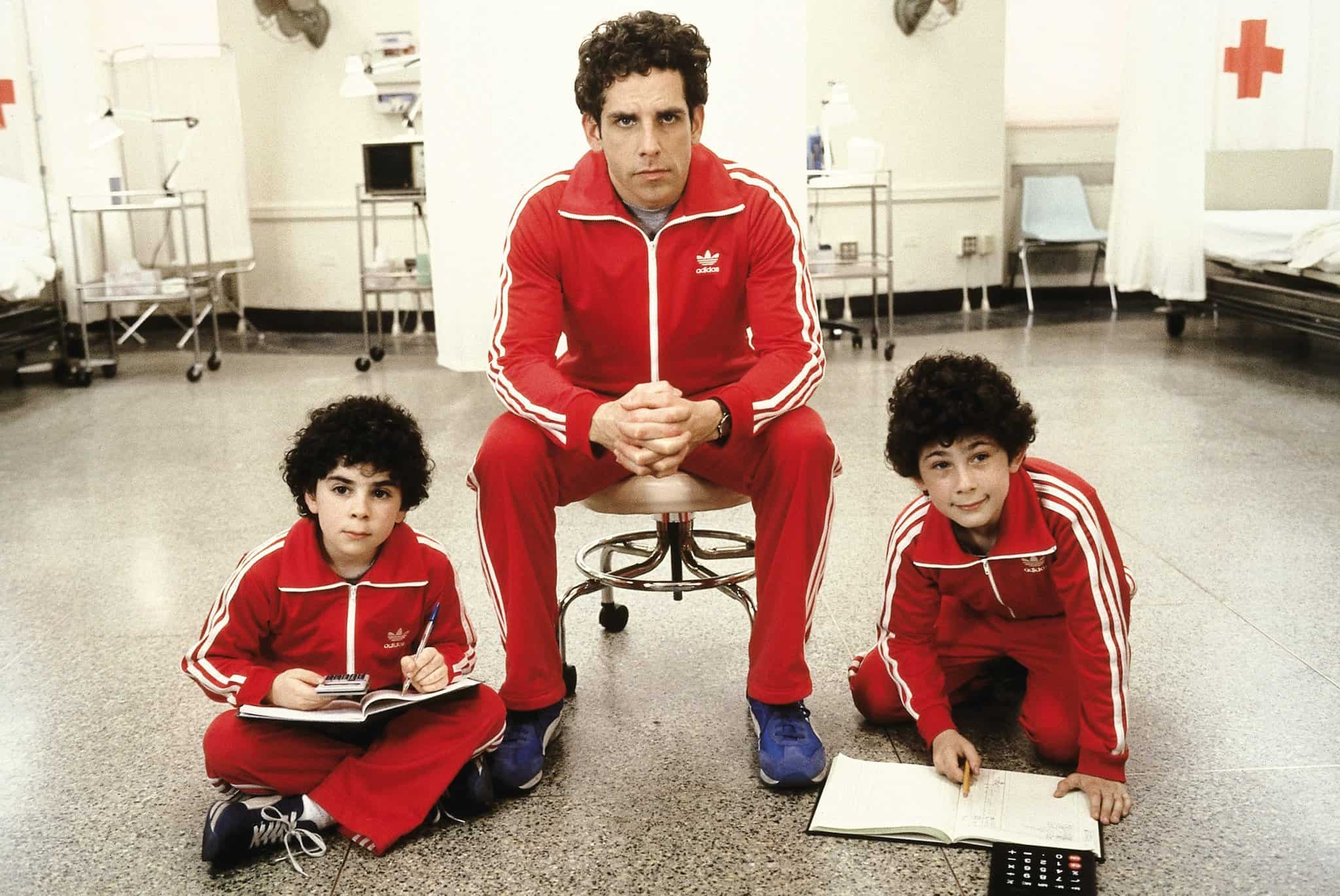

Chas is a widower with two children, hypochondriac and terrified of anything that could remotely endanger him and his children, and his paranoia is also expressed visually, with those identical red tracksuits for himself and the children, a desperate attempt at control and protection from a world perceived as hostile. Margot has married a boring academic and has become apathetic and disillusioned with life, no longer writes and smokes like a chimney confined for hours in the bathroom, her perennial cigarette almost a symbol of a dulled soul and withered creativity. Richie seems to live only for his trained falcon, Mordecai, and his passion for tennis has faded, concealing a secret and tormented love for his stepsister Margot, a forbidden affection that amplifies the sense of isolation and incompleteness that pervades the house.

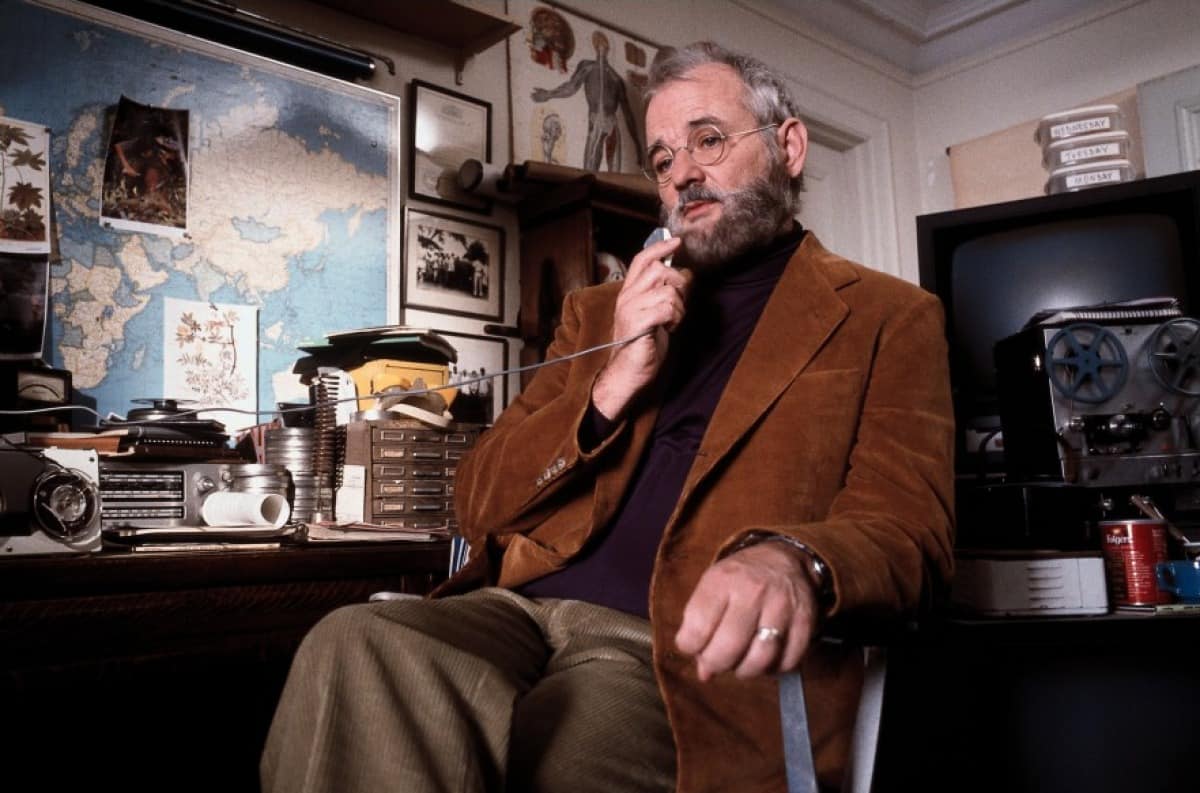

When Royal Tenenbaum, the patriarch, a charismatic and manipulative but at the same time irresistibly charming figure, attempts a reconciliation with his ex-wife to return to live with his family, a minor uproar erupts.

Royal claims to be terminally ill with cancer, but his ex-wife's new partner exposes his deception, leaving Royal no choice but to leave the house again. The lie, in this context, is not just a narrative device, but a key to understanding Royal's personality: a man capable of extreme and dramatic gestures purely to reassert his role, an absent father figure yet perennially present in the emotional scars of his children.

But nothing happens by chance: Royal's pathetic attempt will serve to restore a certain balance in the conflictual relationships among the family members. Paradoxically, it is precisely his dishonesty that triggers a process of emotional honesty among the Tenenbaums, forcing them to confront their own fears and repressed desires. It is a painful but necessary awakening, a mutual admission of vulnerability that opens up avenues for reconciliation.

As in a Russian novel, each character finds a precise place and their evolution is faithfully followed through the filter of narration. The resonance with the literary canon, particularly with the galaxy of J.D. Salinger's melancholic prodigies – one thinks of the Glass family, with their precocious intellects and profound neuroses, or the themes of alienation and the search for authenticity – is almost palpable. Anderson, in fact, does not merely paint portraits, but delves into their psychologies, their idiosyncrasies, revealing the complex interaction between genius, failure, and the perennial need for affection, even if expressed in convoluted ways.

Wes Anderson is one of those directors whose cinematic language is immediately perceptible, like a trademark, making him a true auteur in the purest sense of the term. His aesthetic is a universe unto itself: the manic geometry of every shot, almost a moving dollhouse, where painted backdrops and art objects seem to have a life of their own, contrasted with characters who often move with an awkward, almost marionette-like grace. The color palette, with its warm and retro tones, and the meticulous attention to scenic detail, particularly the iconic Tenenbaum house, contribute to creating a visually distinctive and immersive world.

His cinema is woven with lightness and irony, never heavy, never unbearably pompous. And how can one forget the soundtrack, a genuine soundscape that does not merely accompany but defines the soul of each sequence, transforming tracks by The Ramones, Nico, or Elliott Smith into authentic emotional commentaries, capable of amplifying the melancholic optimism or bitter awareness that pervade every scene.

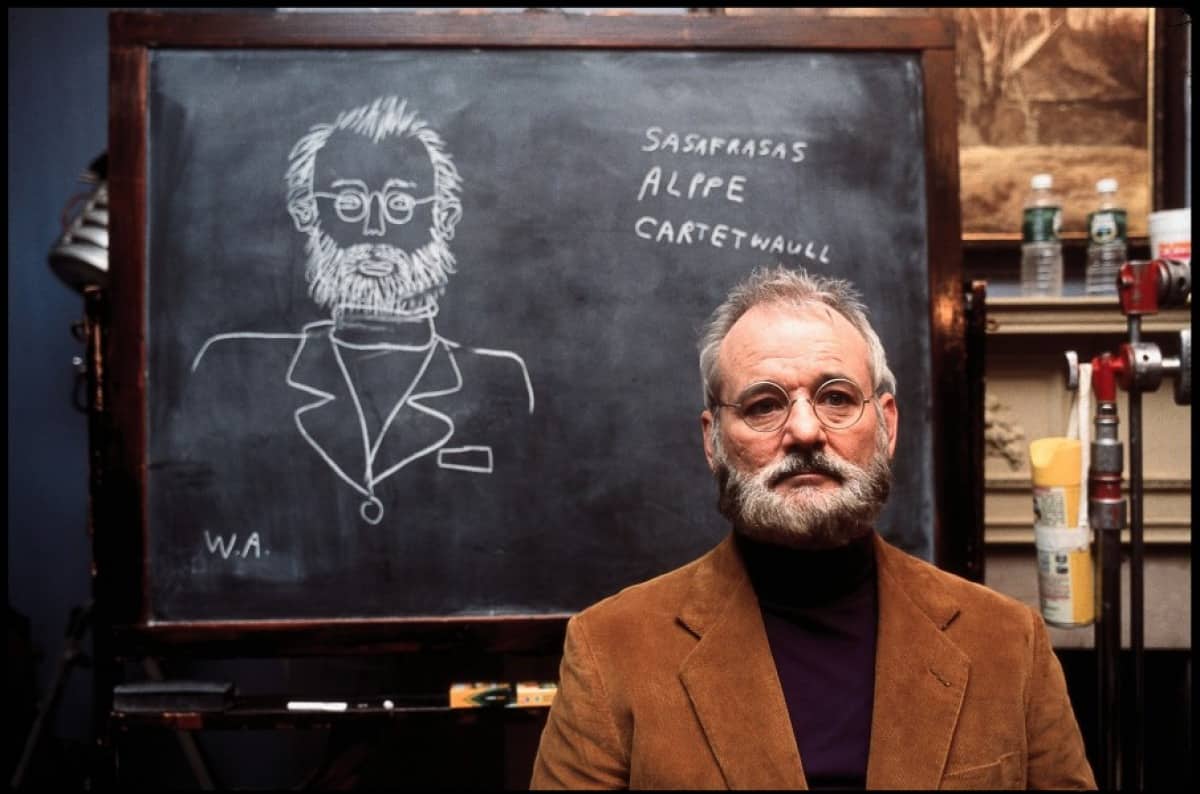

Even when the narrative takes on the decided contours of drama – such as Richie's attempted suicide or Chas's crises – Anderson seems to manage the story with cheerful disenchantment, a way of storytelling that belongs to him and identifies him. It is not a cold detachment, but a lens through which tragedy filters into comedy, and vice versa, leaving the viewer the freedom to perceive one or the other, or both, in a ballet of complex emotions. Gene Hackman's performance as Royal, moreover, is a monument of histrionics and vulnerability, a pillar that still stands out today as one of the greatest performances of his career, capable of perfectly embodying the ambivalence of a character as detestable as he is irresistibly human.

The Royal Tenenbaums is an enchanting film: like a fourteenth-century sonnet, stylistically perfect and ethereal in substance, a complete work of art that continues to reverberate in memory, offering new nuances with each viewing and confirming Wes Anderson as one of the most original and fascinating bards of family dysfunction, nostalgia, and the intrinsic beauty of the unspoken.

Main Actors

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...