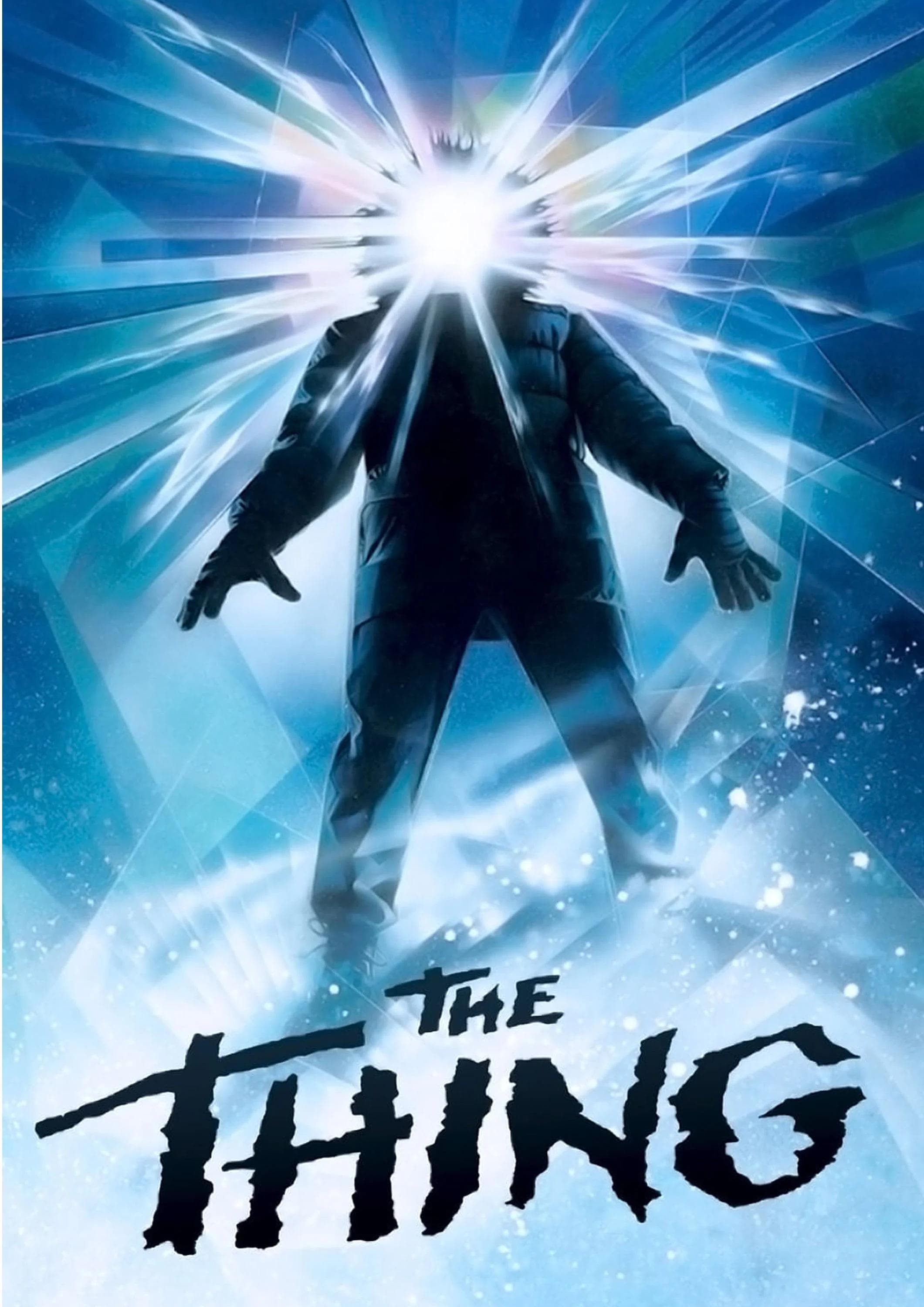

The Thing

1982

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

When Howard Hawks got his hands on John W. Campbell's short story "Who Goes There?" in 1951, adapting it for the screenplay, one of the classics of 1950s science fiction cinema emerged. The film was released in 1951 under the title "The Thing from Another World," credited to the relatively unknown director Christian Nyby, although Howard Hawks effectively co-directed it, albeit uncredited. John Carpenter took this film as a starting point for his personal reinterpretation of Campbell's text, departing from Hawks's work and re-elaborating his own Thriller/Horror version. Carpenter undertook a meticulous deconstruction of Hawks's work, moving away from a pragmatic and largely conventional vision, to immerse his story in a paranoid, distressing, suffocating atmosphere.

Carpenter's reinterpretation is not a mere variation on a theme, but a true philosophical inversion that reflects the disillusionment of the 1980s. Where Hawks, with his post-war optimism, depicted an external threat containable by collective ingenuity and reason – almost an allegory of the Cold War where order prevails over alien chaos – Carpenter plunges headfirst into an abyss of internal paranoia, an ontological disintegration that devours identity itself. His alien is not just an invader, but a biological and psychological contaminant, an entity that does not merely threaten life, but corrupts trust, social bonds, the very essence of human being. This difference is abyssal: Hawks's film is a hymn, albeit a glacial one, to human resilience; Carpenter's is a chilling autopsy of its inevitable, terrifying dissolution. The choice of an all-male cast, in an environment of total isolation, accentuates the crisis of heroic masculinity and traditional group cohesion, often celebrated in adventure cinema.

At an Antarctic research base staffed by an American team, a Norwegian helicopter from another base located further north appears. The aircraft is chasing a Husky dog when it crashes and explodes. The sole survivor of the crash desperately tries to shoot down the dog, but in the commotion, he shoots one of the base members and is killed. The team begins to investigate what happened at the Norwegian base by conducting an inspection there. After examining the evidence found, it becomes clear that the Scandinavian team had exhumed an undefined creature from the ice. Meanwhile, unsettling phenomena occur at the base, and it becomes clear that the awakened entity is hostile and has the ability to duplicate any living organism, simulating its biological and social activities. Among the men at the Base, something is hiding, and some of them are not who they claim to be. Paranoia thus becomes the film's true protagonist, a mental contagion even more insidious than the physical one, resonating with the anxieties of the era, from the nuclear fears of the Cold War to the emergence of new, mysterious pandemics that undermined the perception of security and control.

Leveraging the mastery of the great special effects artist Rob Bottin, Carpenter succeeds in giving tangible form to the nightmare, shaping a kind of indefinable horror that continually changes its morphological structure. Bottin's creations are a triumph of body horror, a catalog of biomechanical aberrations that defy categorization, blurring the lines between organic and inorganic, between life and monstrosity. Memorable are the scenes where the Thing finally comes to light; amidst gore shots, uncertain lights, and clever field changes, Carpenter manages to keep us nervously clutching the armrests of our chairs. But the true greatness of his film lies in the atmosphere of uncertainty that permeates every frame. Carpenter sweeps away the Hollywood theory that brilliant ingenuity and a good dose of courage can lead man to prevail over the Thing from Space, departing from the institutional approach Hawks gave to the story (even with notable aesthetic flourishes).

Carpenter's genius manifests not only in his relentless direction and visceral effects but also in his choice of exceptional collaborators. Dean Cundey's cinematography, with its cold tones and depth of field that amplifies the sense of claustrophobia, transforms the Antarctic base into an ice prison, a labyrinth of corridors and flickering lights where every shadow can hide a threat. And then there is Ennio Morricone's score. Counter-intuitively, Carpenter chose the Italian maestro, asking him to emulate the minimalist and pulsating style Carpenter himself often employed in his films. The result is a soundscape of desolate isolation and growing terror, made of dissonances, deep bass, and deafening silences, which amplifies the sensation of impending danger and a world crumbling apart.

In his film, Man has no point of reference; he is completely at the mercy of events, every social relationship corrupted by distrust, fear, and hypocrisy. The Thing is, first and foremost, a state of mind, a Nihilistic Limbo where every human bond is nullified. The threat is no longer external and visible, but resides in the suspension of knowledge, in the inability to distinguish friend from monster, truth from simulacrum. This radical ambiguity plunges the characters and the viewer into an existential agony reminiscent of H.P. Lovecraft's works, where horror is not only derived from physical monstrosity but from the unfathomable, from the alien in its capacity to annihilate human rationality. Beyond it stretches an infinite sort of Wasteland, a boundless devastation where men succumb to their own fears. The film's conclusion, devoid of catharsis or easy optimism, seals this pact with nihilism, leaving the last survivors not to celebrate a victory, but to contemplate certain extinction, surrounded by eternal cold and a suspicion that can never be dispelled. A film that was misunderstood and lambasted by critics at the time, but which, over the years, has established itself as one of the absolute masterpieces of the genre, a dizzying descent into the abyss of the human condition.

Genres

Countries

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...