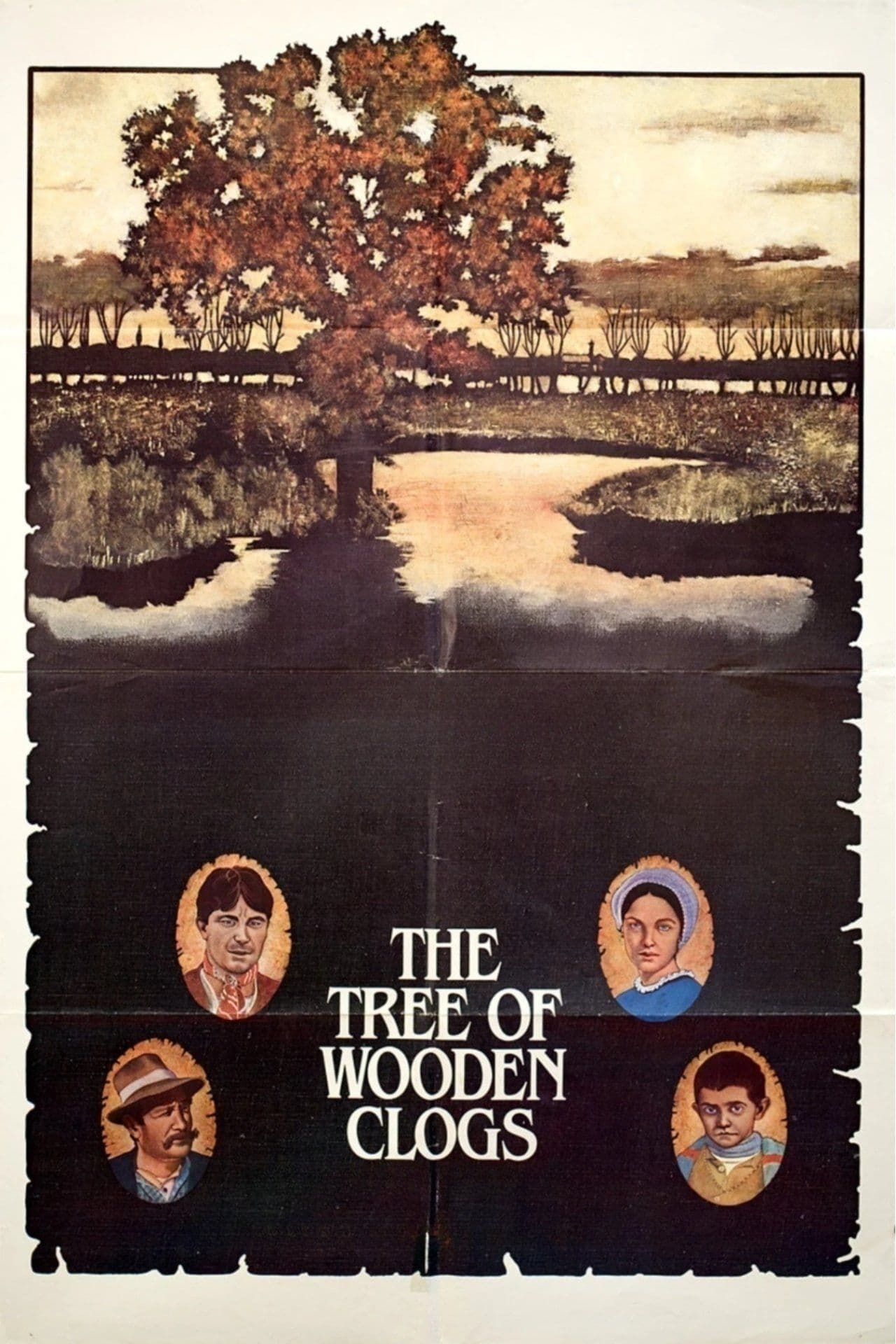

The Tree of Wooden Clogs

1978

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Ermanno Olmi, in what is perhaps his most representative and certainly his most celebrated work, pays a heartfelt and profound homage to his peasant origins and the places of his childhood, weaving the threads of a family saga that unfolds with the slow majesty of a living fresco in the Bergamo countryside at the end of the last century. An era when modernity was still a distant hum, and rural life, though imbued with toil and subordination, preserved an ancestral integrity of its own.

Five peasant families live under the same roof, in a large isolated farmhouse, embodying a microcosm of resilience and interdependence. Their daily lives are marked by exhausting labor for the owner of the surrounding lands, an existence governed by the sharecropping system which, however oppressive, also imposed a rhythm of life in harmony with natural cycles and a solidarity necessary for survival.

Stories and small, yet universal, dramas intertwine among these humble people, but forged by an indomitable spirit and pride. These are events that touch upon childhood, nascent love, loss, illness, quiet rebellions, all faced with a dignity that elevates pain to an art form.

The film takes its title from the ancestral tree, a majestic mulberry that becomes almost a silent and knowing character, from which one of the peasants, with a gesture of paternal love and a subtle, almost unconscious, defiance of imposed destiny, carves clogs for his eldest son, so that he can face the long walk to school without wearing out the soles of his shoes. This seemingly innocuous act, of taking from a resource not his own, will be the catalyst for the tragic epiphany, the reason why the family will be cast out of their home, revealing the brutal logic of power and the precariousness of an existence hanging by the thread of the landlord's benevolence. It is a bitter warning about the fragility of autonomy and the price of knowledge, an incident that encapsulates the eternal drama of class struggle and trampled dignity.

"The Tree of Wooden Clogs" thus reveals itself to be an epic film not for the grandeur of the events narrated, but for the monumental depth with which it investigates the human soul and the values that constitute its lifeblood: inalienable dignity, humility as a path to wisdom, a profound sense of duty towards the land and the community, the sanctity of manual labor, and that popular wisdom handed down from generation to generation which alone allows one to decipher the signs of the world. Every frame is imbued with an almost reverential respect for this peasant culture, for its ancient knowledge and its profound spirituality, even when not explicitly religious.

With Olmi, a new and highly personal season of neorealism opens in Italy, or perhaps it would be more appropriate to define it as a "neorealism of the soul". His works, and "The Tree of Wooden Clogs" is its most shining example, restart from the lessons of De Sica and Rossellini, but sublimate them, enhancing their aesthetic signature where it meets popular traditions, the ancient peasant customs of a land that, precisely at the end of that century, was beginning its slow but inexorable journey towards a modernity that would dissolve all rural identity. Olmi chooses to film reality with a raw truth imbued with poetry, using non-professional actors – real peasants from the area – and shooting for an entire calendar year to capture the nuances of each season, imbuing the narrative with an almost ethnographic authenticity, a slow and meditative rhythm that mirrors the breath of the earth itself. The absence of an intrusive soundtrack, leaving space for the diegetic sounds of nature and labor, contributes to this total immersion.

There is a kind of nostalgic veil, never mawkish but imbued with deep melancholy, behind his powerful depictions; an almost visceral participation in the values that founded and sustained an entire culture, a sense of belonging to that world that cannot be ignored, but rather invites reflection on loss. It is a nostalgia for a lost harmony, a warning about the peasant civilization which, despite its harshness, offered a rootedness and meaning to daily life that "progress" has often dismantled without replacement.

The film won the Palme d'Or at the 1978 Cannes edition, finding the great international recognition it deserves and establishing itself as a timeless masterpiece, a heritage not only of Italian cinema but of all humanity. Its resonance has been global, appreciated for its universality in depicting the human condition beyond geographical and temporal boundaries.

It is certainly a demanding work, not only due to its duration (over three hours), but also its contemplative rhythm which requires the viewer to be open to listening and immersion. Yet, it reveals a poetic verve of rare intensity: a poetry that arises from the humility of small things, from the magnificence of everyday gestures, from the profound wisdom contained in seemingly insignificant details. Emblematic is the episode – a true cinematic gem – of the grandfather explaining to his granddaughter how to plant young tomato seedlings: loosening the soil with calloused hands, digging small holes with his fingertips, watering the seedlings with a few drops of water drawn from an old pitcher. In that simple gesture, an entire philosophy of life is condensed: respect for nature, the transmission of ancestral knowledge, love for the land as a source of life and dignity. It is in these scenes that "The Tree of Wooden Clogs" transcends mere representation to become a meditation on the cyclical nature of existence, on the sacredness of life, and on the uninterrupted flow of time.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...