Thelma & Louise

1991

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Thelma & Louise is not merely a long ode to freedom, to female emancipation, to liberation from every social convention. It is a battle cry against domestic stagnation, a scathing anthem to a freedom gained through force and desperation, and at the same time a profound exploration of the mechanisms of oppression and reaction. In the cinematic landscape of the early nineties, in an era still reluctant to grant full visibility to complex and autonomous female narratives that were not mere embellishment, Ridley Scott's film stood as a bold, almost prophetic manifesto, anticipating discussions on patriarchy and consent that would explode decades later with overpowering urgency.

Thelma & Louise is also a road movie enamored with the places it skirts, a delicate psychological portrait of two women who rediscover their sensibility, until then dormant due to a chilling routine, as they travel together. The car, a '66 Thunderbird convertible, is not merely a means of transport, but an extension of their very will to escape, a protective shell that carries them through landscapes that change as rapidly as their souls transform. From the dusty opacity of Arkansas, symbolizing their suffocating existence, to the grand and enigmatic landscape of the West, every mile traveled is a step towards self-definition. The suffocating daily grind, made of despotic husbands, superficial boyfriends, and insignificant jobs, gives way to a self-discovery woven from liberating laughter, authentic tears, and a female solidarity that crystallizes under the relentless desert sun, transforming them from handmaidens into heroines of a personal epic.

Ridley Scott molds two female figures who have become symbols of rebellion against a patriarchal society that is in many ways oppressive, two veritable icons of nonconformity played out through glances, words, and the fragile complicity of the two protagonists. With his visual mastery and the sensitivity of a screenplay, Callie Khouri's, which won an Oscar and redefined the on-the-road drama, Scott does not merely frame two women on the run, but elevates them to archetypes of an inescapable rebellion. Susan Sarandon and Geena Davis do not merely play characters, but become incarnations of a primordial desire for autonomy. Their on-screen chemistry is palpable, a rare alchemy that allows the viewer to believe, with every fiber, in the genesis of this indissoluble sisterhood. It is in their interaction, in the glances they exchange, in the way mutual support becomes the only beacon in a world that seeks to punish them, that the film's true strength lies. Their nonconformity is not a pose, but a direct consequence of their spiritual and material awakening.

The story told hinges on the casus belli in which the two women kill a vile assailant in a public parking lot. This seemingly incidental act is not a mere narrative device; it is the Gordian knot that unties Thelma and Louise's chains, pushing them beyond the point of no return. It is an act of self-defense that society, in its patriarchal inertia, cannot and will not understand or forgive. The film does not judge their reaction, but acutely and intelligently explores the consequences of a choice dictated by necessity and accumulated frustration, revealing the hypocrisies of a judicial and social system that often condemns victims and protects aggressors, or at least offers no real and safe escape routes. The scene itself, in its raw and immediate brutality, is a punch to the gut that immediately defines the terms of their new existence: outside the law, but paradoxically more authentic and free than ever.

From that moment, their flight begins, carrying them from Arkansas to Oklahoma. The flight is not just a geographical trajectory from one border to another, but a progressive stripping away of social masks and self-imposed inhibitions. The road, in its infinite horizon, becomes a metaphor for freedom but also for limits, an existential labyrinth from which one cannot escape without facing it to the very end.

As the police close in on them, the two young women experience the road as a prism that restores dormant sensations, unexplored landscapes, atmospheres never before savored. While Agent Slocumb (an empathetic Harvey Keitel), almost a modern Tiresias capable of grasping the complexity of their motivations, tries to understand and anticipate them, the two women shed others' expectations: Thelma transforms from naive and dependent into an audacious thief and strategist, demonstrating unsuspected cunning; and Louise, the more pragmatic and rational of the two, reveals her vulnerability and tormented past, adding layers of psychological depth that make their odyssean flight a journey not only spatial, but also internal. The road movie genre, usually dominated by male figures seeking redemption or escape – one need only think of "Easy Rider" or "On the Road" – here takes on unprecedented nuances, centering female liberation as a political and profoundly personal act, a courageous subversion of genre tropes.

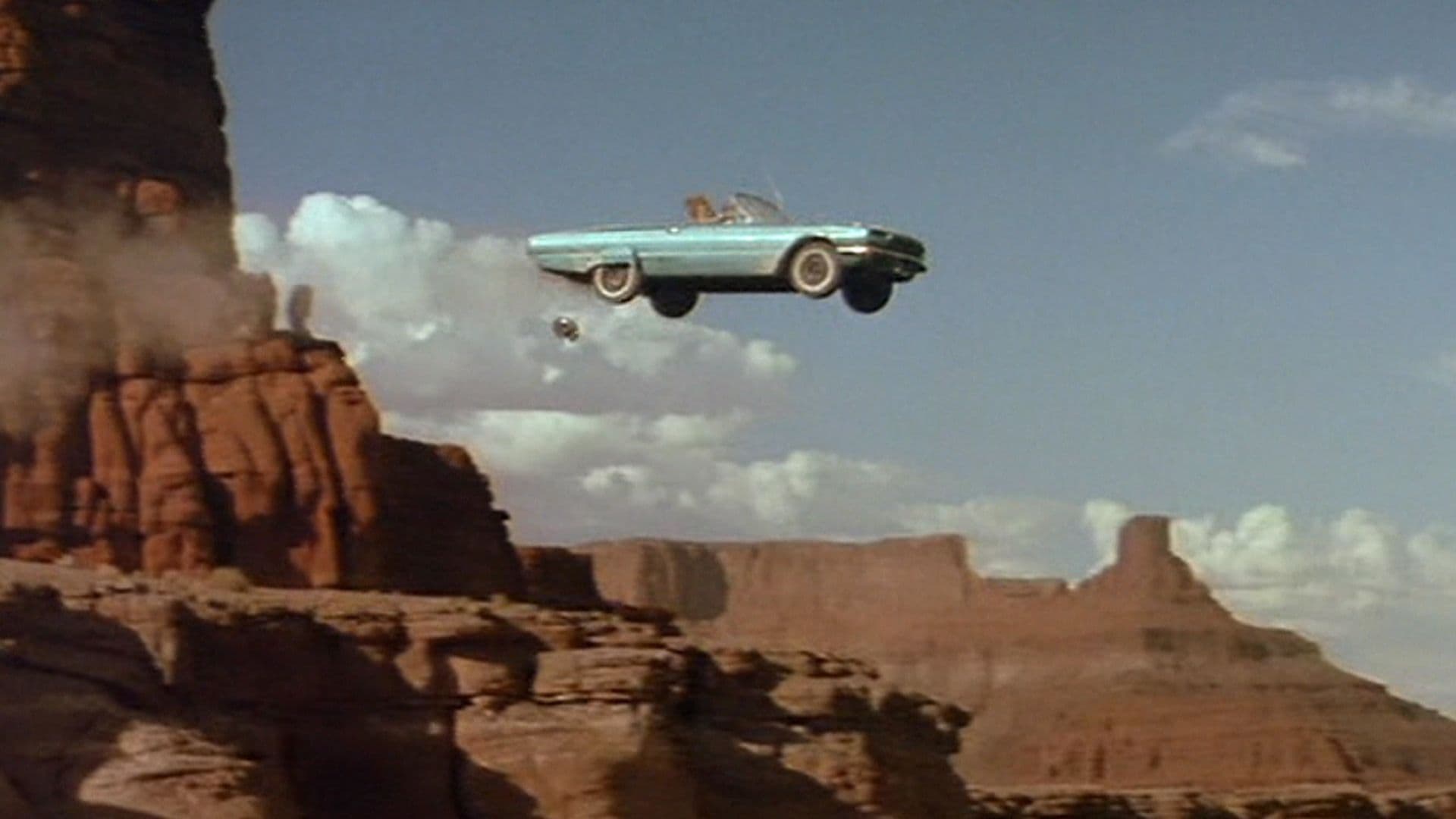

A customary mention for the final scene: the stop-motion flight of the car plunging into the abyss and the close-up shot of the two smiling faces, has rightly entered the collective imagination, becoming a sort of viral wallpaper imprinted on the desktop of our minds. The obligatory mention of the epilogue is insufficient to grasp its seismic echo. That final scene – the car launching itself into the Grand Canyon, suspended in an eternal moment of sublime freedom before an inevitable epilogue – is not merely a conclusion, but an affirmation, a manifesto in motion. It is a frame indelibly imprinted on the collective retina, not for its intrinsic tragic nature, but for its ineffable charge of triumph and defiance. It is an image that defies gravity not only physically, but also socially, recalling the ecstasy and melancholy of other cinematic destinies of no return, such as that of Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde, but with a specific resonance linked to the female will for self-determination against all forms of coercion. The choice to fly instead of surrender becomes a symbol of voluntary martyrdom, an extreme act of protest against a system that offers no escape, yet which the women refuse to legitimize through their submission. That smile, caught in the fatal moment, is a seal on an unwavering pact of loyalty, a beacon that illuminates the meaning of a totalizing freedom, even if ephemeral.

Thelma and Louise do not yield to society's oppressiveness, do not retreat from those who hunted them, do not choose the easier path. There is no surrender, no repentance, only an undeniable self-affirmation, a silent scream that propagates beyond the screen, defying conformity and predestination.

On the contrary, theirs is an apology for freedom, for the most absolute liberation from every bond; their smile, dissolving into the void, is a rend in the soul of all of us. Theirs is an act of defiance not only against the law, but against the very concept of "acceptable" or domesticated femininity. It is a memento mori not to death itself, but to a life not fully lived until one has dared to defy the limit, until the last breath of autonomy. That smile dissolving into the wind is not a sign of defeat, but an exultation that reverberates in the soul of anyone who has ever felt the weight of conventions or the grip of oppression, reminding us that true freedom sometimes lies in the ability to refuse compromises, even when the price to pay is physical annihilation. It is a rend in the soul of all of us, because it strikes the universal chord of the search for authenticity and the courage to be, against all odds.

Main Actors

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...