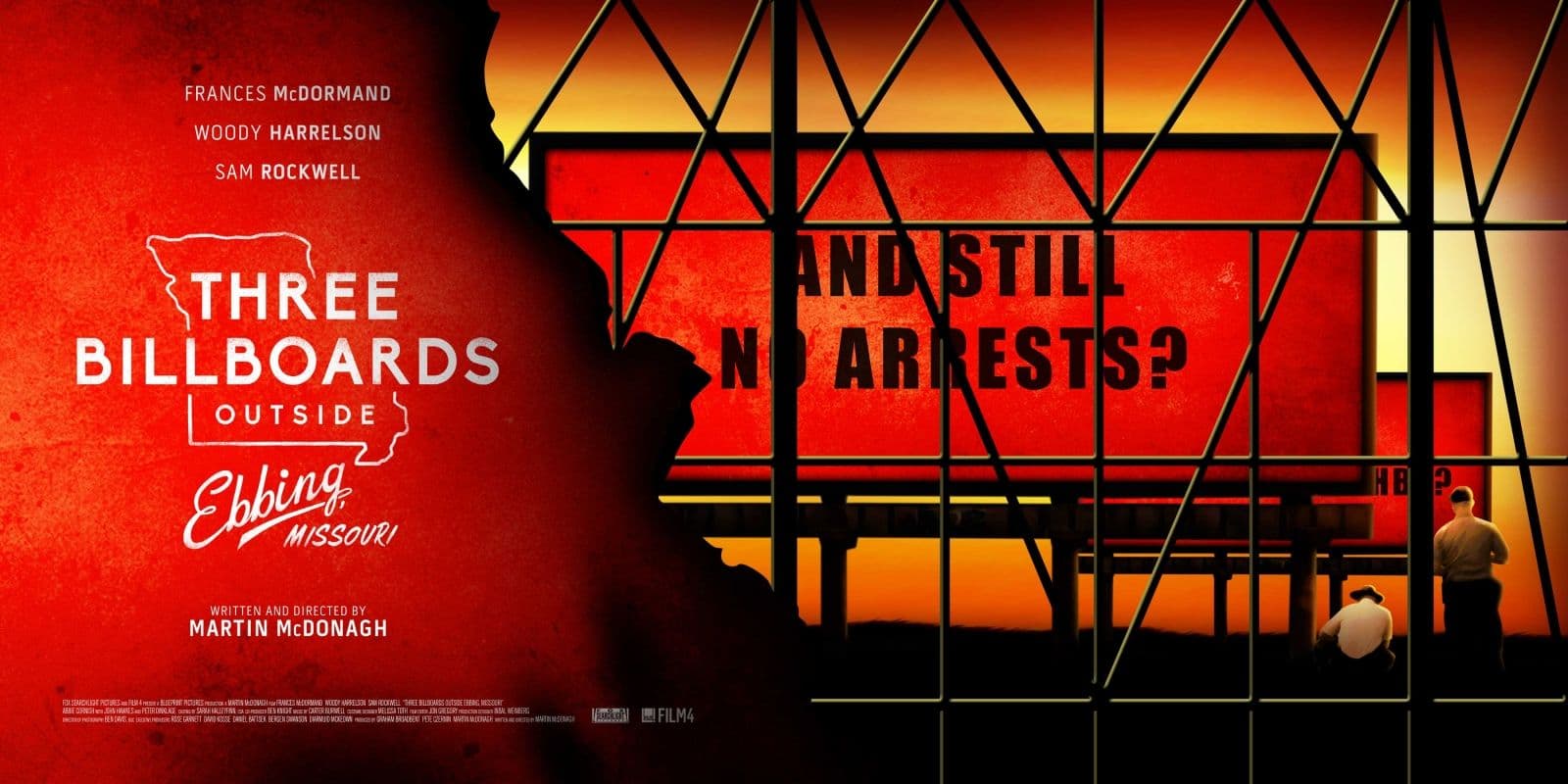

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri

2017

Rate this movie

Average: 4.33 / 5

(3 votes)

Director

Martin McDonagh, with his third film, swept the awards, bringing home something like 5 BAFTAs, 4 Golden Globes, and 2 Oscars. Not a particularly prolific director, the author of two interesting films that skillfully blend the thriller genre with black comedy: In Bruges (2008) and Seven Psychopaths (2012), in this third effort he stages a story balanced between black humor and crime story, featuring a female character who will go down in cinematic history for her fierce sense of justice. The success with both critics and audiences for McDonagh is by no means accidental, but the natural consequence of an authorial journey deeply rooted in theatre. A world-renowned playwright, his works such as The Pillowman or The Beauty Queen of Leenane are celebrated for their tight dialogue, sharp cynicism, and ability to extract flashes of humanity from brutal situations. This theatrical sensibility translates into his cinema as an extraordinary attention to dialogue, which here becomes a privileged vehicle for tension and black comedy, and in a mise-en-scène that, while cinematic, maintains the intensity and surgical precision of a chamber drama.

The protagonist of the story is Mildred Hayes, a divorced single mother, interpreted with titanic mastery by Frances McDormand. Mildred is a difficult person to be around. Understandably so, since only seven months have passed since her teenage daughter, Angela, was found raped and murdered near their home in Ebbing, Missouri. Mildred harbors an atrocious and morbid thirst for justice to find who did this to her daughter. But to define Mildred's as a "thirst for justice" is almost an understatement, if not simplistic. It is rather a festering wound that, instead of healing, becomes infected and spreads, dragging down anyone who comes near it. Her crusade is a detonation of pain and repressed rage, a primal scream that defies conventions and unhinges institutions. Mildred does not seek justice in the commonly understood legal or moral sense; she seeks a form of cathartic revenge, a way to give a voice to her lost daughter, even if that voice is strident and dissonant. McDormand, with her rough mask and smouldering eyes, embodies a modern Medea, a tragic figure who does not hesitate to sacrifice her own peace and that of others on the altar of an ideal of retribution. Hers is a rebellion against inertia, against complicit silence, against a system that seems to have abandoned her.

She drives through the town in her old wood-paneled station wagon, dressed in worn-out work overalls, her gaze fixed straight ahead. She has no patience for relaxing pleasantries with the local priest, who comes to her house for a cup of tea and a word of comfort, and who is instead served a monologue on pedophilia in the Catholic clergy. Mildred, steeped in her bitter cynicism, even scoffs at her son Robbie; she never lowers her guard, never indulges in tenderness so as not to let the tension on her goal subside. In fact, the woman never misses an opportunity to blurt out the horrific details of Angela's murder to everyone she meets. Finally, Mildred decides to take things up a notch. She notices three unused billboards on the road leading to Ebbing and conceives the idea of renting them with personalized messages addressed to the local police chief, Bill Willoughby (Woody Harrelson). Mildred's messages are an attack on the Police and their inconclusive investigations.

The department is doing everything possible, Chief Willoughby assures her, although it is not reassuring that the police officer assigned to the case is a violent, insensitive man like Agent Dixon (Sam Rockwell), known in town for his mistreatment of black suspects in custody. Agent Dixon, portrayed with an Oscar-winning performance by Sam Rockwell, is not just a comedic foil or a mere antagonist. He is the embodied symbol of a deep and troubled America, a land of contradictions where racial prejudice is an ingrained blight and police brutality a routinely accepted reality. His evolution throughout the film is one of McDonagh's most audacious and controversial plot twists: from a stereotype of the racist and irresponsible police officer, Dixon gradually emerges as a surprisingly complex character, capable of a fragile and ambiguous redemption, inviting the viewer to confront their own capacity for empathy and forgiveness. This narrative arc, which has sparked considerable debate about its veracity and message, is emblematic of McDonagh's desire to escape easy moral categorizations, pushing the audience beyond the comfort of narrative Manichaeism.

McDonagh creates a credible and self-contained microcosm. And unlike the bewildered heroes of In Bruges and Seven Psychopaths, Mildred is part of a broader, more certified social landscape. For better or worse, she belongs to Ebbing, even if most of its inhabitants, including her ex-husband (John Hawkes), consider her crazy. McDonagh skillfully paints a myriad of secondary characters who are more than mere extras: the manager of the dilapidated office that rents the billboards (Caleb Landry Jones), a bar patron in town with a long-standing crush on Mildred (Peter Dinklage), or the even more wicked mother of Officer Dixon's son (Sandy Martin). Each character, however marginal, contributes to painting a vivid and merciless fresco of provincial America, where lives intertwine in a tangle of resentments, distorted affections, and shattered hopes. The universe of Ebbing, in essence, becomes a magnifying glass on the cracks in the American dream, an investigation into latent violence and the mechanisms of self-destruction that can stem from unexpressed pain and repressed rage. The three billboards, from simple objects, transform into a powerful symbol: they are the three prongs of an attack not only on a single local police force but on an entire society that prefers stasis over action, convention over uncomfortable truth. It is no coincidence that the film was released during a historical period of great social ferment, resonating with discussions about institutional responsibility, gender-based violence, and social justice, while maintaining its timeless universality in the portrayal of grief and its distorted processing. McDonagh's direction is a masterful balance between the darkest drama and an irrepressible, at times surreal, comedy that lightens the tension without ever diminishing the gravity of what is at stake.

Ebbing is a kind of canvas steeped in these figures, a land stretching from the grubby confines of the police station to that lonely stretch of country road with its three accusatory billboards. And over everything looms the mystery of Angela's death, as if connecting every atom of the landscape, every emotion at play, with a deathly thread. And above all this stands the extraordinary figure of this Woman, who rises above everything and cries out with every cell of her Being her maternal thirst for justice. This film does not merely tell a story, but questions the viewer about the nature of good and evil, the complexity of the human soul, and the possibility, or not, of finding redemption in a world that seems to have lost it. An audacious, uncomfortable work, destined to remain etched in collective memory not only for its shower of awards but for the courage to confront thorny issues with rare clarity and an unmistakable style.

Main Actors

Genres

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...