Tokyo Story

1953

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Yasujirô Ozu, one of the greatest Japanese directors alongside Kurosawa and Mizoguchi, speaks to us through the poetics of everyday life, the soul of small things. His greatness does not lie in the epic grandeur of a Kurosawa or the poignant melodrama of a Mizoguchi, but rather in an extraordinary ability to capture the subtlest nuances of human existence, transforming the mundane into the universal, the domestic into the sublime. His camera, often placed at a low height as if inviting the viewer to sit on a tatami mat alongside the characters, observes life with an almost Zen calm, devoid of dramatic exasperations but dense with profound emotional resonance. Ozu does not show explosive emotions; he suggests them through eloquent silences, fleeting glances, and the patient observation of time's decay.

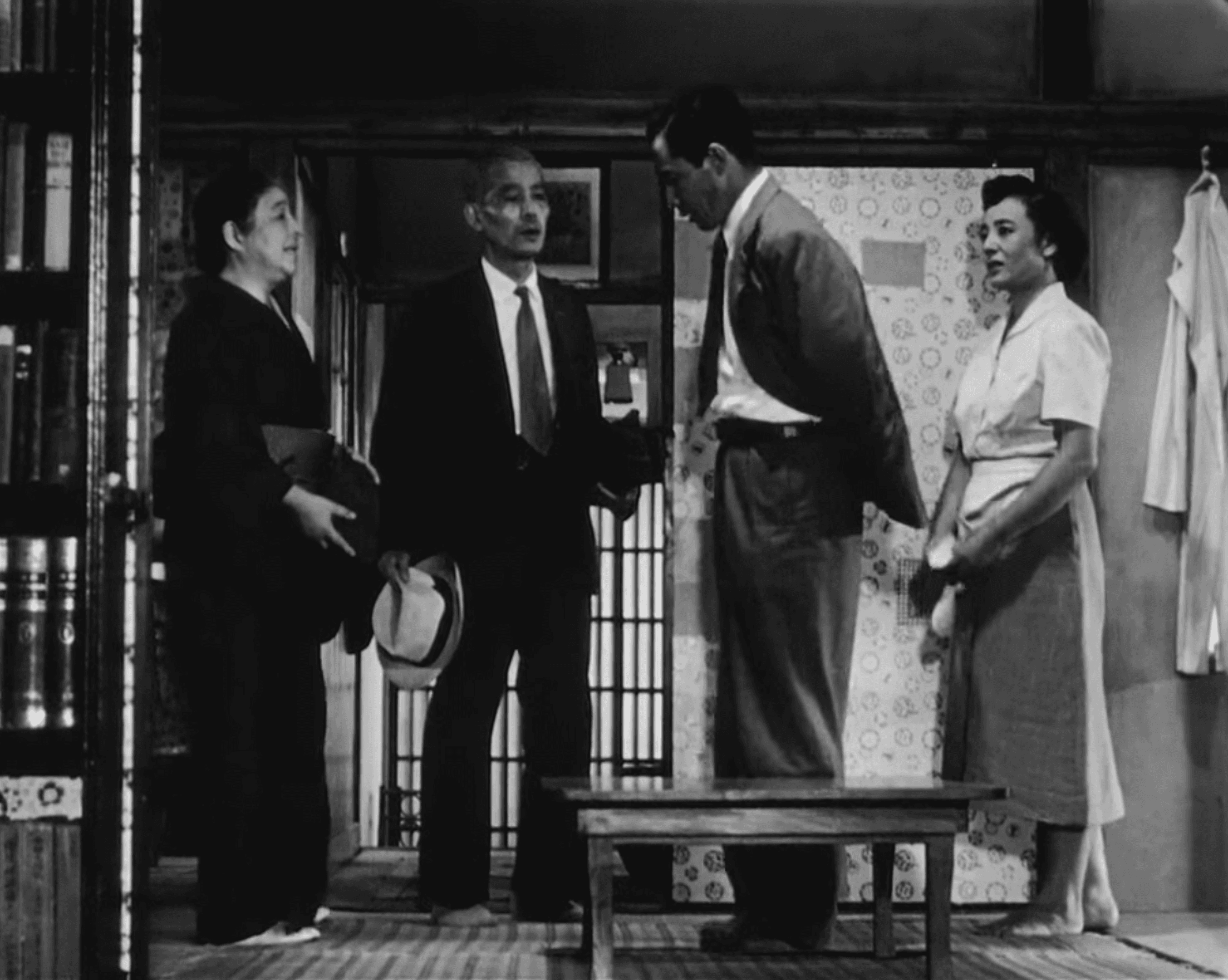

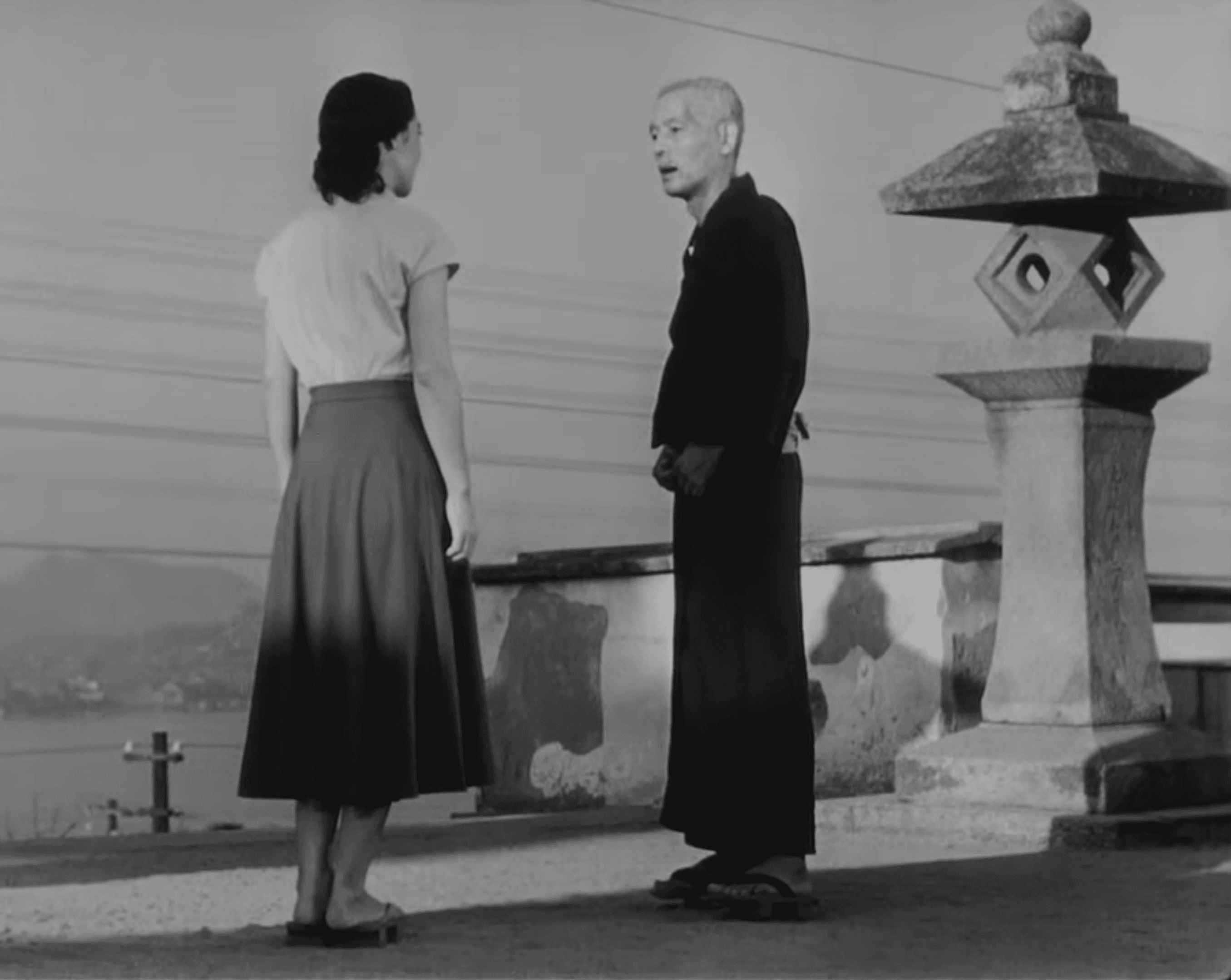

In this delicate film, he tells the story of an elderly couple, Shukichi and Tomi Hirayama, originally from the small coastal town of Onomichi – a place that in Ozu's imaginary evokes a rural past and traditional harmony – who decide to journey to the great metropolis of Tokyo to visit their two married children, Koichi, a scrupulous doctor absorbed in his profession, and Shige, a practical and less sensitive hairdresser, along with their respective families. This journey is not merely a geographical displacement but a true symbolic passage between two eras, two lifestyles: old age and tradition attempting to meet the frenetic and, to some extent, ruthless modernity of post-war Japan.

Upon their arrival in the great city, the alienation raging around them will also translate into their relationships with family members. Indeed, the children will pay little attention to their parents, treating them as nuisances, an unexpected burden in their already overburdened lives. This indifference is not necessarily malicious, but rather a reflection of an era of rapid change and a Japanese society that, geared towards reconstruction and the "economic miracle," was silently sacrificing family ties and the veneration of elders in the name of progress and individual well-being. Ozu captures with disarming honesty the painful truth that children, once the center of their parents' world, are now themselves the center of a self-referential universe, incapable of empathy or a simple gesture of shared time.

The couple will, however, receive love and a surprising dose of compassion from a person not strictly related by blood: Noriko, the widow of their son Shoji, who died in the war. The young woman, with her infinite grace and quiet sacrifice, will do everything to make the elderly visitors comfortable, offering them a welcome that their own children fail to provide. Noriko represents a beacon of humanity in a world that seems to have lost its moral compass, the embodiment of Ozu's mono no aware: the poignant awareness of the impermanence of things, but also the beauty found in their transience and in the acceptance of life, with its joys and its unavoidable bitterness. It is she who utters the memorable and heartbreaking line: "Life is always disappointing, isn't it?", a phrase that encapsulates the entire philosophy of the film, a disillusioned realism that does not, however, preclude the possibility of finding beauty in resignation and kindness.

A work thus centered on the incommunicability between generations and the sense of estrangement inflicted by the metropolis, but which expands far beyond. It is an existential fresco on the dissolution of the traditional Japanese family (ie), on the loneliness that accompanies old age, and on the cyclical nature of life, where children will in turn become elderly parents and experience the same, inevitable, distance from their own descendants. Ozu paints this picture with a palette of subtle yet incredibly powerful colors, using seemingly simple direction – fixed shots, almost absent camera movements, minimal and often repetitive dialogues – which creates a contemplative, almost hypnotic rhythm. The famous "pillow shots," frames of urban landscapes or inanimate objects that serve as transitions between scenes, are not mere intervals but moments of respite for the viewer, small visual poems that reflect the fleetingness of time and the serene acceptance of the external world, indifferent to human dramas.

A film that is a cornerstone of cinematic art and that we cherish in our hearts like an invaluable gem. Its influence has been enormous, extending far beyond Japan's borders: its ability to capture life in its purest form, without dramatic artifices, has inspired generations of directors, from Wim Wenders, who dedicated his documentary "Tokyo-Ga" to him, to contemporary slow cinema filmmakers, fascinated by his aesthetic of contemplation. Its relevance is perpetual because the themes it explores – the passage of time, family relationships that evolve or fracture, the individual's loneliness in modern society – are universal and resonate with the same force today as in 1953, the year of its release. Every viewing of "Tokyo Story" is a cathartic experience, an invitation to reflect on one's own existence and the bonds that define us.

Also noteworthy is the splendid work by Tucker Film, which recently restored and compiled six of Ozu's masterpieces into a Blu-ray box set – works that had been missing from shelves for some time: a cultural operation of inestimable value that allows a new generation of viewers to access these cinematic treasures, rediscovering the quiet, yet immense, greatness of a master who was able to speak to the soul of the world with the delicacy of a whisper. A must-see for every film enthusiast.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...