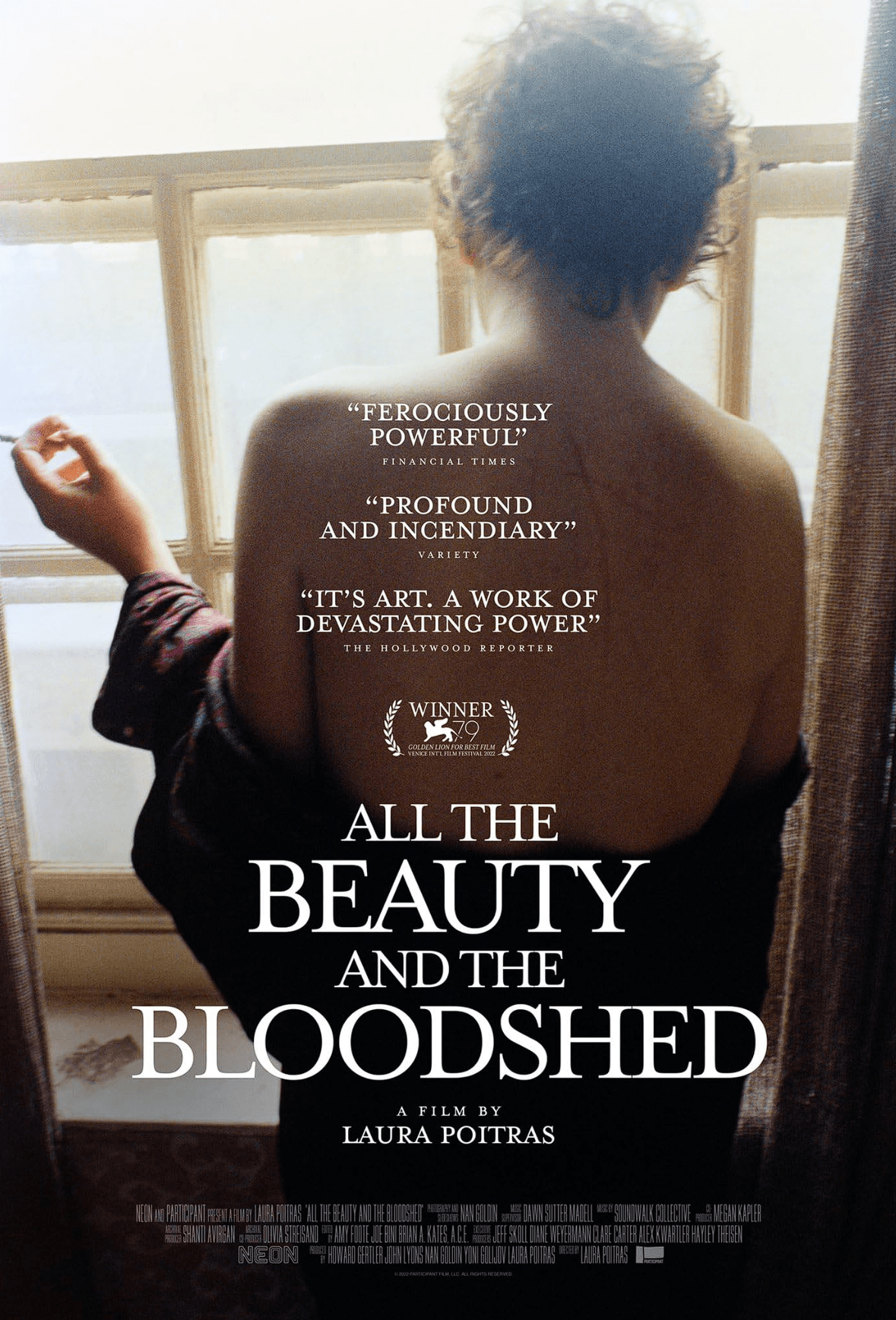

All the Beauty and the Bloodshed

2022

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

There are documentaries, and then there are works like Laura Poitras's All the Beauty and the Bloodshed. It's not a film, it's an indictment. It's not a biography, it's an autopsy. It's not a story, it's a weapon. Winner of the Golden Lion at Venice (an almost mythological feat for a documentary), Poitras's film transcends every genre definition to become a ruthless and remarkably lucid treatise on power, memory, and art's ability not only to bear witness to pain but to transform it into an act of justice. It's a work that gets under your skin and consecrates its protagonist, photographer Nan Goldin, as an icon of resistance that is as intimate as it is political.

The film's most brilliant stylistic feature, and the key to understanding its intent, lies in its double-helix structure. Laura Poitras, who previously dissected the architectures of power in Citizenfour, masterfully intertwines two timelines that illuminate each other. In the Present, we follow Nan Goldin and her activist group, P.A.I.N., in their almost suicidal crusade against the Sackler family, the toxic patrons of art who enriched themselves by creating and fueling the opioid crisis with OxyContin. This part is filmed like a spy thriller, with meticulously planned protest actions ("die-ins") in sacred art temples like the Guggenheim and the Louvre. It's the chronicle of David against a pharmaceutical and philanthropic Goliath.

In the Past (The Intimate Confession): Through her own photographs and her hoarse, melancholic voice, Goldin guides us on a journey through her life. It's not a conventional biography, but an immersion into her archive of scars: her sister Barbara's suicide, crushed by suburban respectability; the discovery of a "chosen family" in the queer counterculture of Boston and New York; the brutality of domestic violence; the devastation of AIDS; her own addiction. Poitras doesn't simply alternate these two stories: she demonstrates that they are the same story. The anger of the present is fueled by the pain of the past.

This is the director's intent and the film's powerful metaphor: the Sacklers are not an anomaly, but the most recent symptom of a systemic American and, more broadly, capitalist disease. The parable Poitras constructs is crystal clear: the same forces that led to her sister's death—the stigmatization of diversity, the control of non-conforming bodies through punitive psychiatric language, the hypocrisy of a prudish society—are the very same that allowed AIDS to decimate her community amid general indifference, because the victims were "others" (gay, addicts, artists). And these are, once again, the same forces that allowed the Sacklers to profit from pain, knowing that the primary victims of opioid addiction would be marginalized people, whose suffering was, for the system, an acceptable cost. The film demonstrates that the phrase "all the beauty and the bloodshed" is not a simple juxtaposition. The pain (the spilled blood, bloodshed) is the price paid by certain communities so that another part of society can enjoy "beauty" (the profits, the museum wings named after patrons, a feigned respectability). Poitras's intent is to unveil this obscene connection.

To understand Nan Goldin's struggle, one must understand her art. Her photography is the antithesis of a glossy aesthetic. It is an act of brutal realism and unconditional love. With her celebrated series The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, Goldin did something revolutionary: she elevated the intimate, messy, and often painful moments of her life and that of her "tribe" to artistic subject matter. Her images of drag queens applying makeup, of lovers in bed, of bruised faces, are not voyeurism. They are testimonies. In this, Nan Goldin is Caravaggio's direct heir. Just as the Baroque master scandalized his era by using the faces of prostitutes and commoners to represent Madonnas and saints, so Goldin finds the sacred, beauty, and a profound humanity in the faces and bodies of those society would prefer to ignore or conceal. Her camera does not judge; it sanctifies.

It is precisely because she has spent her life making the invisible visible that her fight against the Sacklers acquires an unassailable moral weight. She is not just any activist; she is a priestess of memory who has seen her community decimated twice by two different epidemics, born from the same matrix of greed and indifference. Her film tells us that every photograph, every work of art, every personal memory can become a weapon when a community decides that its pain will no longer be silenced. And this, more than any other, is a lesson that deserves a place of honor in the Canon.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...