Umberto D.

1952

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Vittorio De Sica delves into mannered decadence, painting a story of solitude and marginalization, a stark and relentless depiction of abandoned old age in a post-war Italy that, rising from the rubble, seems to have lost its most compassionate soul. This is not the collective resilience of Bicycle Thieves nor the violated innocence of Shoeshine; it is rather the intimate chronicle of a silent disintegration, an almost final act of Neorealism that crystallizes its most painful and least conciliatory essence.

Umberto Domenico Ferrari must contend with life and its squalid pitfalls, struggling to live in a small rented room, whose misery is proportional to the social invisibility of its occupant. His daily struggle is not against overt enemies, but against systemic indifference, against a ruthless economy that does not forgive weakness and does not recognize the value of a life spent in the service of the State. He is tyrannized by his landlady, a grotesque yet cruelly realistic figure, who humiliates him daily, embodying the new opportunistic bourgeoisie that tramples the dignity of the lowest in the name of profit. His only glimmer of human connection is the young cleaning woman, Maria, who, despite being pregnant and forced to work hard, shares with Umberto a silent pact of solidarity in suffering, a fragile bridge of humanity in a world that is rapidly dehumanizing itself.

A bitter and somber film, with a truly pulsating screenplay, excellently penned by the great Cesare Zavattini, whose theoretical approach to "pedinamento" (tracking) finds one of its purest and most radical expressions here. The film is recounted without false drama, a stylistic choice that reflects Zavattini's philosophy of recording life as it presents itself, in its most prosaic and least sensational everyday reality. The camera does not seek the striking event, but dwells on small humiliations, repeated gestures, on the slow wearing down of existence. This almost documentary adherence to reality confers a disarming authenticity on the work, a realism so profound it borders on a lyricism of desolation.

Even when Umberto calls the ambulance and is taken to the hospital, there is no tragedy, no fear of dying within him. Illness, like hunger and solitude, is another stage in an already predetermined path, a simple mechanical inconvenience for a body that no longer has a purpose. Later, when Umberto considers suicide as the only solution to end his suffering, he contemplates it in such a calm and logical way that we are able to calmly follow his reasoning, weighing the alternatives with him, and instead of being manipulated by terror, our attitude, like that of the protagonist, is calm, cold, rational. This rejection of melodrama is perhaps the most audacious and intellectually stimulating aspect of the film. De Sica and Zavattini deny us easy catharsis, forcing us to confront the naked, ineluctable logic of despair. There is no room for easy tears or pre-packaged answers; only the painful realization of a man who, after a life of honest work, finds himself facing the abyss of nothingness, deprived of all dignity and reason for existing.

De Sica avoids any temptation to transform his hero into one of those amiable Hollywood old-timers played by Matthau and Lemmon, or into pitiful figures from a commedia all’italiana. His is a precise choice of artistic rigor, a form of resistance to the growing tendency, even in Italian cinema of the time, towards a "pink neorealism" that was more sugar-coated and comforting for the audience. Umberto D. was, not coincidentally, a commercial and critical failure upon its release, perceived as too "negative" by an Italy that wished to forget its wounds. But precisely in this intransigence lies its timeless greatness. The lead actor, Carlo Battisti, a retired university professor and not a professional actor, was a courageous choice that further reinforced the character's authenticity, making him not an interpretation, but a presence, almost an archetype of the forgotten pensioner.

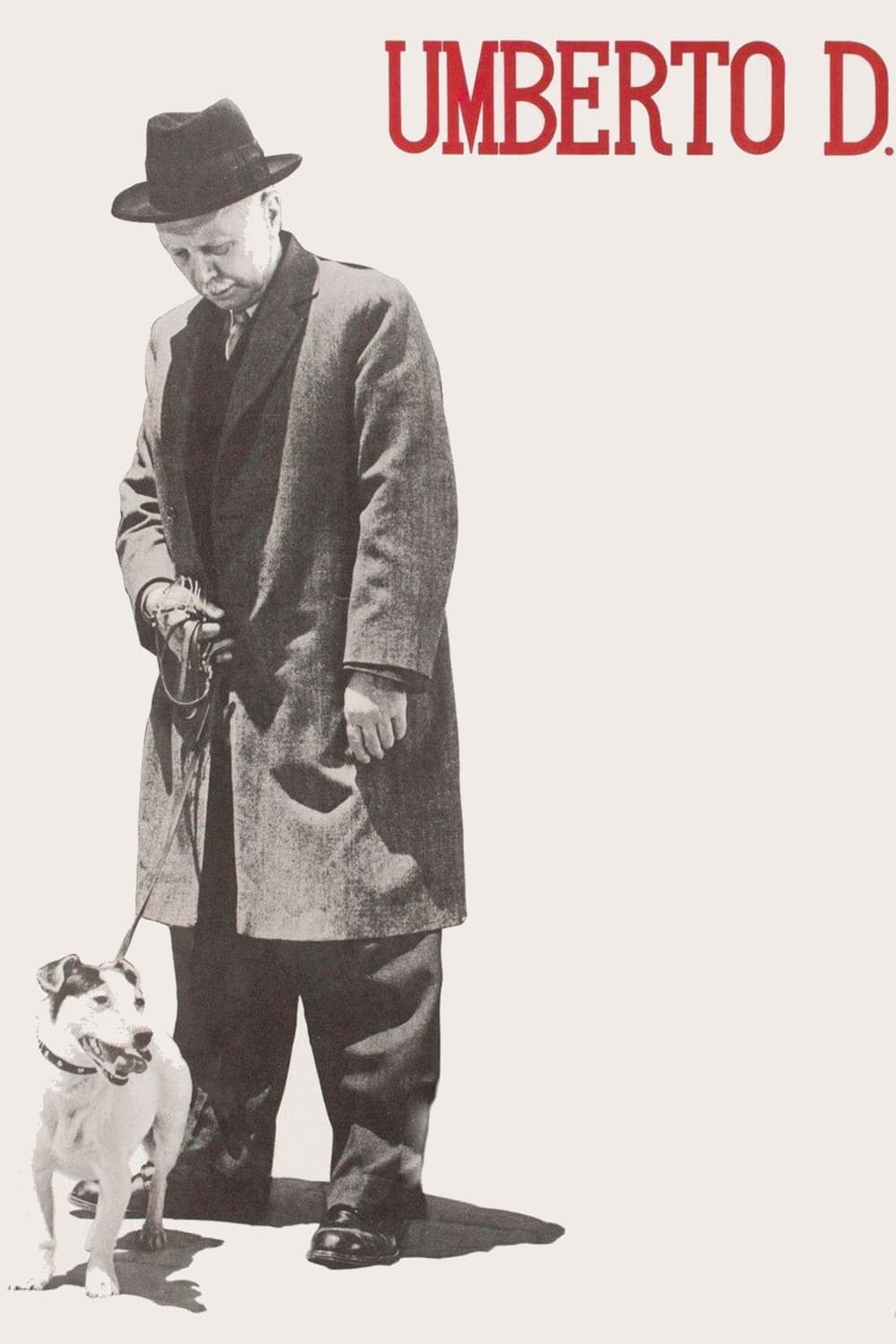

Umberto Domenico Ferrari is not life magically transforming into Commedia dell’Arte, but a man who wants to be left alone to go about his daily activities, asking for nothing else. His only companion, his only fixed point in a crumbling world, is his inseparable dachshund, Flik. The relationship between Umberto and his dog is the film's pulsating and unexpressed heart, the only true emotional bond that keeps him anchored to life. It is through Flik that Umberto rediscovers fragments of his humanity, his tenderness, his capacity for care and love. The iconic scene in which Umberto tries to abandon Flik, only to be pursued by his faithful companion, is an emotional punch to the gut, a culmination of the protagonist's despair and, at the same time, a harrowing affirmation of unconditional loyalty. It is Flik who prevents him from throwing himself under a train, not for a melodramatic plot twist, but for the pure, unbearable reality of the bond between two vulnerable beings.

And the viewer can only identify with him, hoping to face life in the same way: not only with courage and resourcefulness, but with a stoic dignity in the face of the absurdity of existence. Umberto D. thus stands as a testament to an era and a universal warning about the fragility of the human condition, a masterpiece of melancholy that continues to resonate with a rare and moving power, far beyond the confines of its time and genre.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...