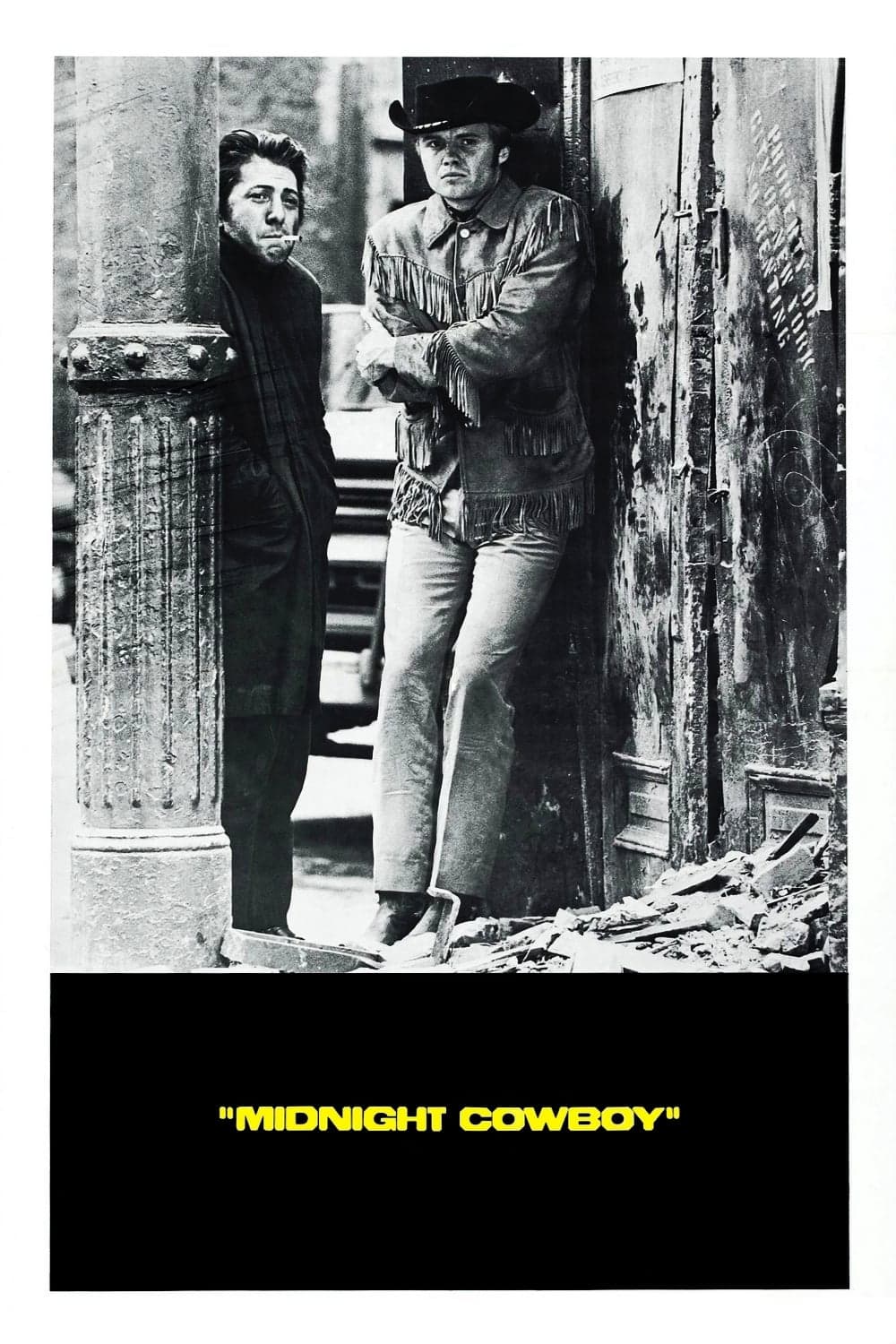

Midnight Cowboy

1969

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A magnificent film about metropolitan alienation and the difficulty of communicating with one's fellow humans, helmed by a highly inspired Schlesinger and featuring a truly extraordinary Dustin Hoffman, in his second major role after The Graduate. A work that, in the cinematic landscape of 1969, stood as a burning and prophetic warning, a flash of honest cruelty in the heart of a fermenting America, destined to shatter the illusions of the preceding decade. Hoffman's contribution, here already an actor of uncommon sensitivity, transcends mere interpretation; he embodies the disillusionment of an entire generation, the fall of myths, and the emergence of a new, painful reality. His transformation from Benjamin Braddock, an icon of bourgeois rebellion, to the naive and dreamy Joe Buck, marks a point of no return in his career and in the very conception of the cinematic hero, no longer pristine and perfect, but fragile, profoundly human, and defeated. It is no coincidence that Midnight Cowboy was the first and only film with an "X" rating (at the time equivalent to today's NC-17, reserved for pornographic or extremely controversial material) to win the Oscar for Best Picture, a bold decision that underscored the Academy's willingness to acknowledge a new, ruthless, and authentic cinema.

A young man from the provinces, Joe Buck, arrives in New York laden with hopes and a naive, anachronistic self-image as a gallant and charming "cowboy." He ends up working as a gigolo, a distorted and degraded version of his desired identity, with the help of Rico, a drifter living by his wits on the fringes of society. His descent is not merely a geographical journey from rural Texas to the asphalt jungle, but a true initiatory ordeal into the brutality of the metropolis. New York, in this film, is not just a backdrop, but a character in itself: a voracious and indifferent creature that chews up and spits out dreams, a labyrinth of solitude and oppression. Joe's illusions clash with a reality made of squalor, vulgarity, and exploitation, forcing him into a prostitution not only of the body but also of the soul, selling an image of masculinity he himself struggles to recognize.

A strange yet profound friendship develops between the two, a bond that leads them to escape the surrounding metropolitan squalor in an attempt to fulfill the dream of endless sun and freedom in Florida. This improbable symbiosis between the young, handsome, and naive cowboy and the old, sick, and cynical vagabond becomes the pulsating heart of the film. It is not a conventional friendship, but a desperate co-dependency, a search for mutual salvation in a world that seems to have abandoned them both. The dream of Florida is nothing but a mirage, a last, fragile hope clinging to the promise of an untouched elsewhere, the final shred of a corrupted and crumbling "American dream." It is a primal desire for warmth and dignity that sharply contrasts with the oppressive grayness of Manhattan's streets, captured by cinematography that is unafraid to explore the city's rawer, more melancholic side.

The character of Rico (Ratso in the original edition, portrayed by a rarely intense Jon Voight) is the keystone of the entire narrative structure. His resentment towards the society that relegated him to the margins, forcing him to struggle to survive, is the sentiment that best describes Schlesinger's work. Ratso is not merely a parasite, but a prophet, an urban Tiresias who has witnessed too many deformities and paid an exorbitant price. His sharp intelligence and fiercely protective cynicism are the armor that conceals a profound vulnerability. He dictates the rules of survival in that urban jungle, providing Joe with a distorted but necessary guide, in a relationship that is as much mentor as exploiter, but which evolves into something far more complex and moving. The scene where Ratso, crossing the street, is almost hit by a taxi and shouts the unforgettable "I'm walking here!" was not in the script, but an improvisation by Voight that perfectly captures his rebellious nature and fighting spirit, becoming one of the most iconic and quoted moments in cinema history.

His bitterness is the bitterness of the vanquished; his unpleasant physical appearance and his infirmities (he is lame and has tuberculosis) are sublimated in Joe Buck's athleticism and prowess. This physical contrast is a powerful metaphor: Ratso is the sick body of a sick society, whose refuse spills onto the most marginalized figures, while Joe, with his superficial beauty and apparent health, is the vehicle through which Ratso attempts to rise again. It is as if Joe absorbs the weight of Ratso's despair, carrying around not only his hopes but also his pain, in a kind of secular transubstantiation. This dynamic is also reflected in the crisis of masculinity that the film explores, presenting two archetypes of failed men in the context of an America redefining its values and idols.

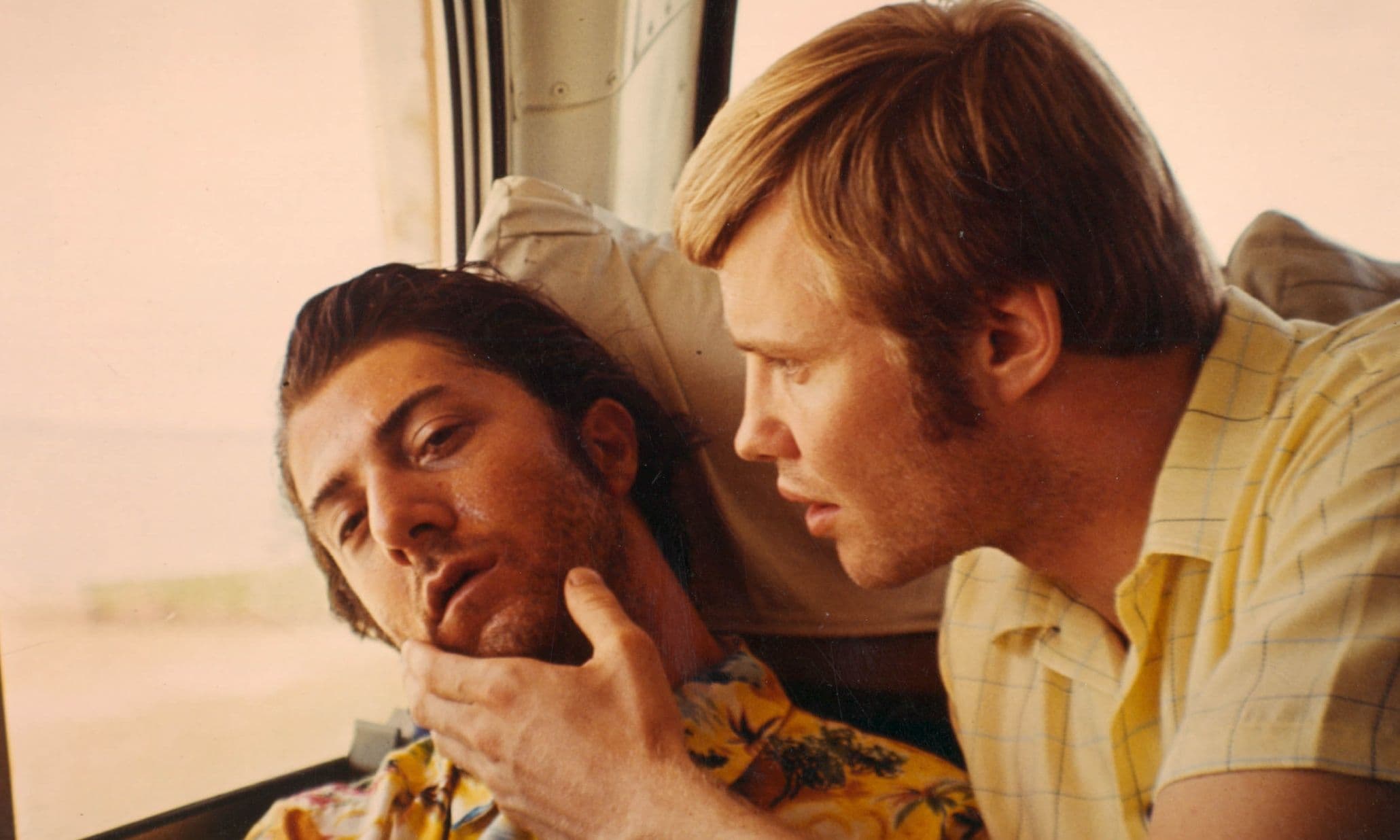

Ratso, upon meeting Joe, understands he has a hope for redemption, transferring all his searing desire to survive a mechanism that has torn him apart into that clean-cut boy. It is a desperate search for a ray of light in an existence of darkness, an attempt to cling to someone who still represents a lost purity. The heartbreaking and unforgettable ending, on the bus bound for Florida, seals their bond in a tragedy that is simultaneously an act of love and surrender. The image of Joe holding Ratso's lifeless body in his arms, as the sun begins to dawn through the window, is one of the most poignant and iconic in New Hollywood cinema, condensing the fragility of dreams and the cruelty of fate into a single frame. It is the triumph of an imperfect and desperate humanity, capable of finding a glimmer of solidarity even in the deepest abyss.

A harrowing work on marginalization and the desire for redemption, but also an uncompromising fresco of an era, a warning against the rhetoric of success and well-being at all costs. Schlesinger's film is a milestone that successfully captured the anguish of a decade, the disintegration of the American dream, and the emergence of a new wave of directors and actors who were unafraid to explore the darkest recesses of the human soul and society. Its influence is palpable in subsequent works that continued to plumb the dark side of metropolises and the solitude of outcasts, from Taxi Driver to Panic in Needle Park, confirming its stature as an enduring classic and a powerful testament to a cinema that dared to face the truth.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...