Videodrome

1983

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Max Renn is always looking for shocking content to broadcast on his television channel, Channel 83. A minor broadcaster, perpetually hungry for scandalous material, operating on the fringes of television decency, a mirror of an underground culture seeking increasingly extreme sensationalism.

When he stumbles upon Videodrome, a series featuring scenes of unparalleled savagery and violence, he is almost hypnotized. It's not mere brutality that captivates Max, but rather the disturbing authenticity of what appears to be a genuine snuff movie. That visual extremism soon reveals itself not to be a mere television program, but a door to the unknown, a kind of lysergic tunnel where consciousness is obliterated through a mystifying process that induces hallucinations and a death wish. The viewing is not passive; it is a contagion, an audiovisual virus that inoculates an altered reality directly into the viewer's temporal lobe. Max's perception, and with it his very identity, begins to fragment under the assault of cathodic impulses.

Investigating the program's origins, he discovers that its producer, the sprawling Spectacular Optical, run by Professor Brian O'Blivion and his pragmatic right-hand man Barry Convex, intends to dominate the world by annihilating the will of its viewers. This is not a trivial conspiracy for power, but an attempt to reshape reality itself, to purge society of what O'Blivion calls the "old flesh," corrupt and weak, to bring forth a "new flesh" molded by violence and the renunciation of individual consciousness. The metaphor concerning the realm of media, and particularly TV, is all too clear, yet its depth goes beyond a mere warning.

Through the luminous box, sinister spells radiate, subverting consciences, instilling false desires and a distortion of reality. The film, permeated by a visceral anguish, anticipates by decades debates on "augmented reality" and the pervasiveness of the image. Cronenberg, who explicitly draws inspiration from Marshall McLuhan and his theory that "the medium is the message," elevates television from a simple transmitter to an organic and manipulative entity. The medium does not merely convey content; it itself becomes the content, a prosthesis of the central nervous system capable of reprogramming it. Hallucination becomes real, the body becomes a screen, and the soul merges with the distorted signal.

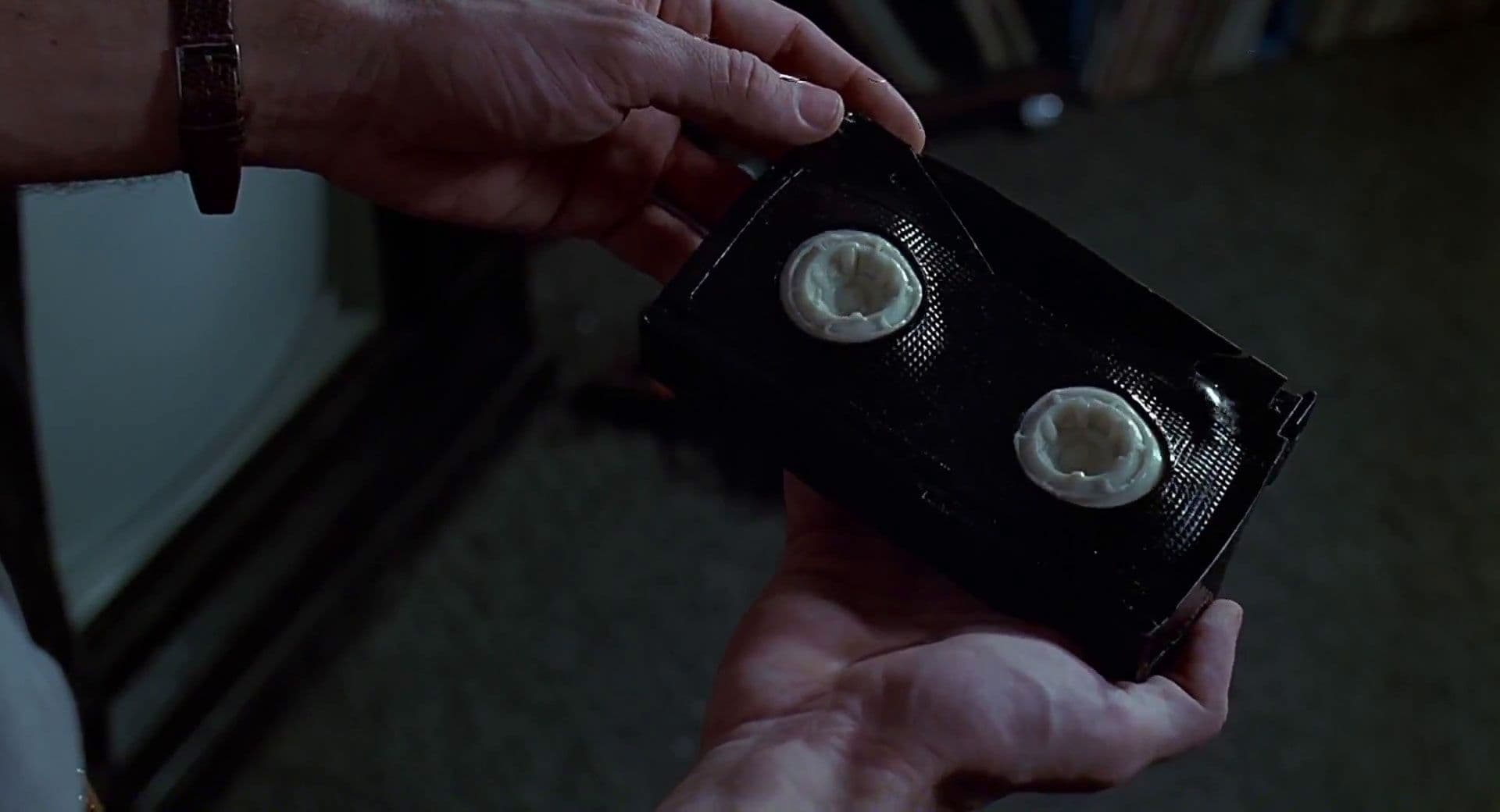

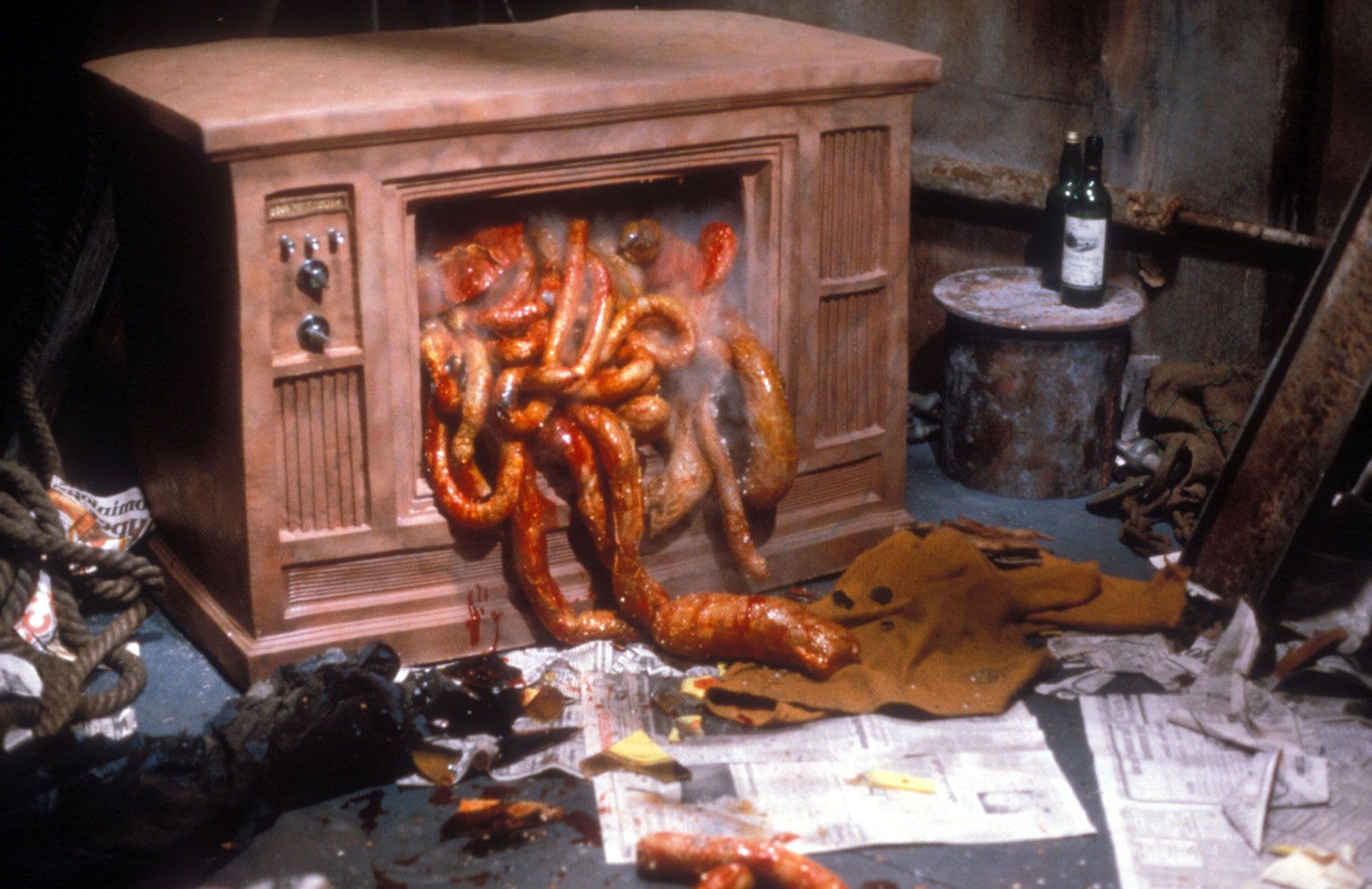

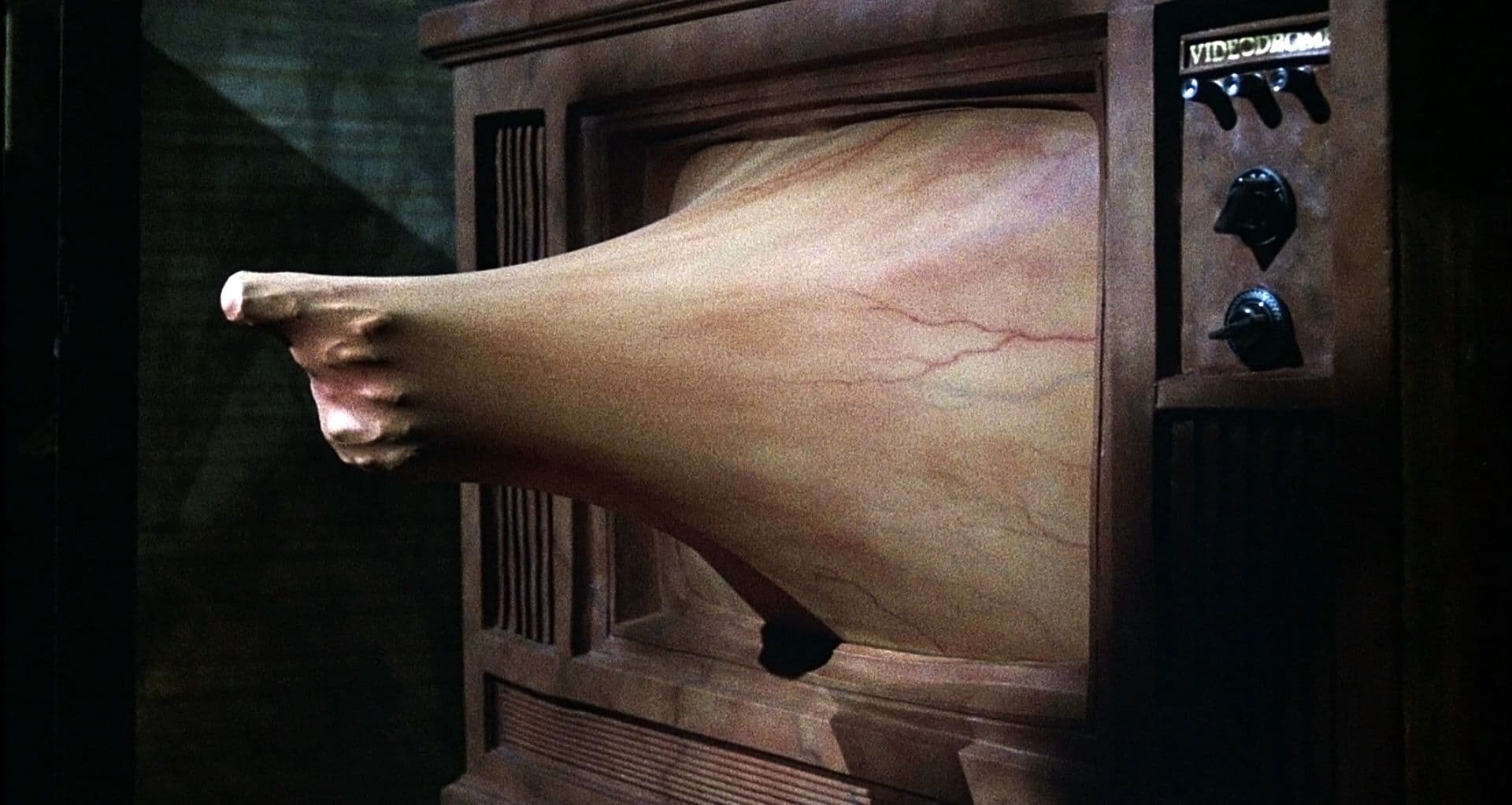

Beyond the critique of media power, there is a profound analysis of the relationship between man and machine, between brain and information, which is the pulsating heart of Cronenbergian aesthetics. The Canadian director translates dark and disturbing atmospheres onto film to define the relationship between critical consciousness and message, between reality and cathodic hyperuranium. This dichotomy between the self and the televised other is a synthesis of a technological paranoia that permeates much of his filmography, from Scanners to Crash, from Naked Lunch to eXistenZ. In Videodrome, the organic and the mechanical are no longer separate entities but interpenetrate in an aberrant and terrifying symbiosis, made tangible by Rick Baker's pioneering special effects, which transform Max's body into a biomechanical nightmare. The famous VCR slot that opens in his abdomen or the pistol that fuses with his hand are not mere visual horrors, but manifestations of his irreversible mutation. Max is no longer a mere spectator, but the battlefield upon which true evolution is waged.

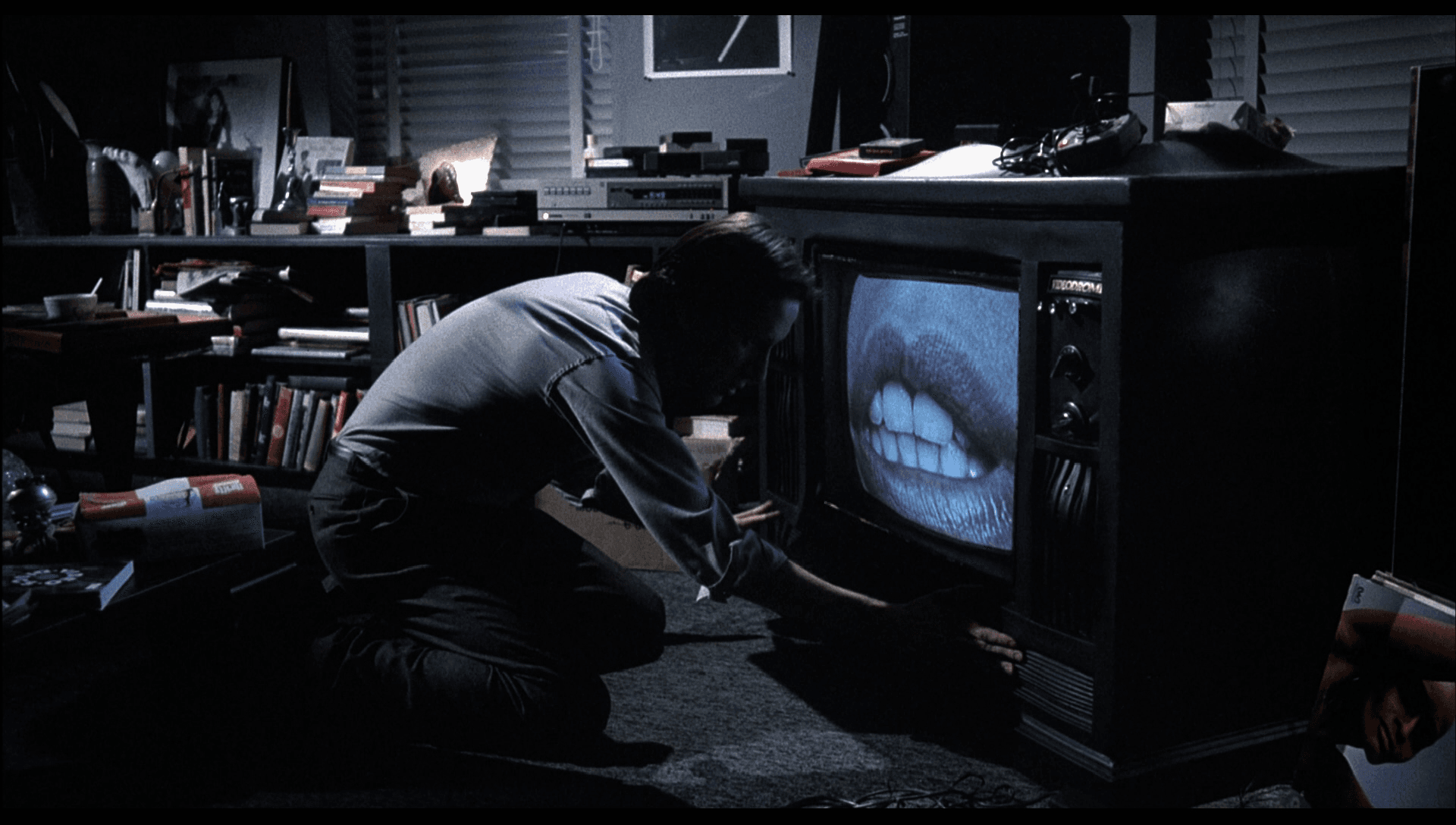

This fusion is synthesized in the marvelous scene where Max faces a captivating Nicki Brand (Debbie Harry) who, from the TV screen with overflowing sensuality, invites him to join her. Nicki is not just a femme fatale, but the embodiment of the "new flesh," a digital siren drawing him into the abyss of transformation. The TV shakes, swelling and vibrating as in an erotic game where the viewer is the designated prey. Max slowly approaches the screen, stroking the TV, while Debbie Harry's fleshy mouth in the foreground seems to spill out of the screen, her shiny, inviting lips extending beyond the frame, like a fleshy appendage seeking contact. When Max's head and the screen unite almost by osmosis, forming a single entity, the fusion between man and media can be said to be complete: consciousness is drowned in the spell of the transmission, and the viewer has been definitively consumed. But what seems like annihilation is, for the proponents of Videodrome, a rebirth. The final scene, with Max, uttering the mantra "Long live the new flesh!", shooting himself in the head, is not a suicide, but a further and definitive mutation, an evolutionary leap into the cyberspace of flesh and signal. "Videodrome" is not just a film about the horror of technology, but about the seduction of an uncertain and terrifying future, an unsettling warning that resonates now more than ever in our era of virtual realities, deepfakes, and digital dependence.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...