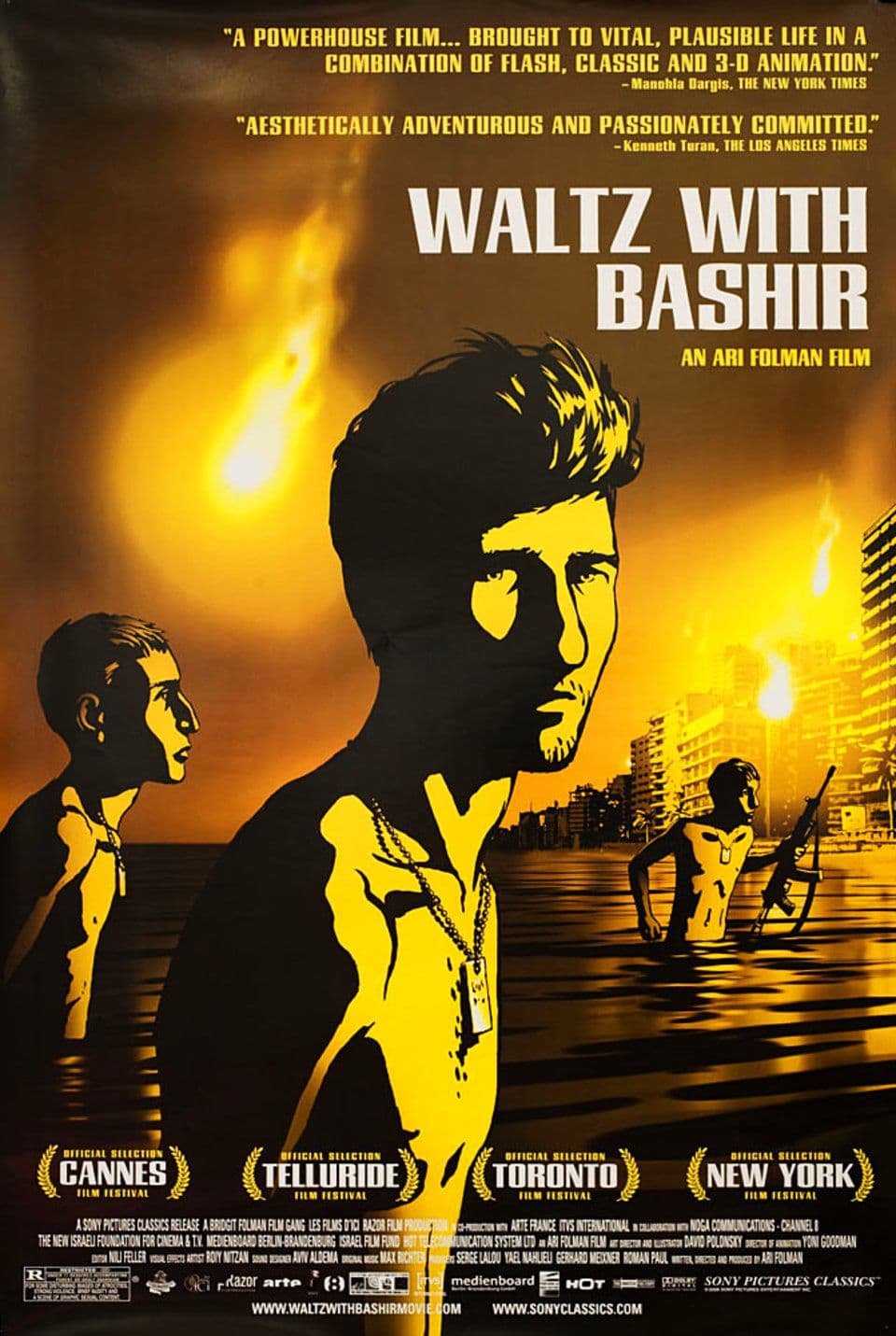

Waltz with Bashir

2008

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Ari Folman's film is a thriller of memory, an open-air psychoanalysis session, a police investigation in which the investigator, the crime, and the victim are one and the same. It is a work that, with a formal audacity bordering on the miraculous, has invented a new language to describe the indescribable: trauma. Folman does not limit himself to using animation as a stylistic device; he chooses it as the only possible tool for mapping the treacherous and hallucinatory geography of repressed memory, creating a cinematic experience that is both a feverish dream and a lucid confession. This film does not ask to be simply seen; it asks to be witnessed.

The premise is a journey into the darkness of one's own mind. An Israeli filmmaker, Ari Folman himself, realizes that he has a black hole in his memory regarding his experience as a young soldier during the 1982 invasion of Lebanon. Driven by a recurring nightmare of a friend, a pack of twenty-six ferocious dogs chasing him through the streets of Tel Aviv, an image of almost biblical power that opens the film, Folman decides to interview other veterans of that conflict to reconstruct his lost memories. Each interview is not a simple collection of facts, but the trigger for a fragment of memory, a piece of a psychological puzzle that slowly comes together, piece by piece. The film thus becomes a perfect allegory of the psychoanalytic process: the search for truth does not come through sudden revelation, but through the “work of memory,” a painful journey in which the stories of others serve as a mirror to illuminate the dark corners of one's own psyche.

On this journey, the theme of the Israeli-Palestinian war is addressed with a courage and intellectual honesty that are rare, especially in Israeli cinema. Folman performs an act of national self-criticism of devastating power. The culmination of his personal investigation is his presence, and that of the Israeli army, on the outskirts of the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps during the massacre of Palestinian civilians perpetrated by Christian Phalangist militias. The film offers no easy answers or absolution. It explores the gray area of complicity, the responsibility of the witness who does not act, the guilt of the soldier who obeys orders. The perspectives of the artist, the man, and the soldier are not separate, but are three fragments of a shattered identity struggling to reconcile themselves.

The artist feels an ethical duty to remember, the man is terrified of what he might discover, and the young soldier he once was has put in place the most powerful of defense mechanisms: forgetting. It is in the content of the interviews and in the memorable scenes that the choice of animation reveals all its genius.

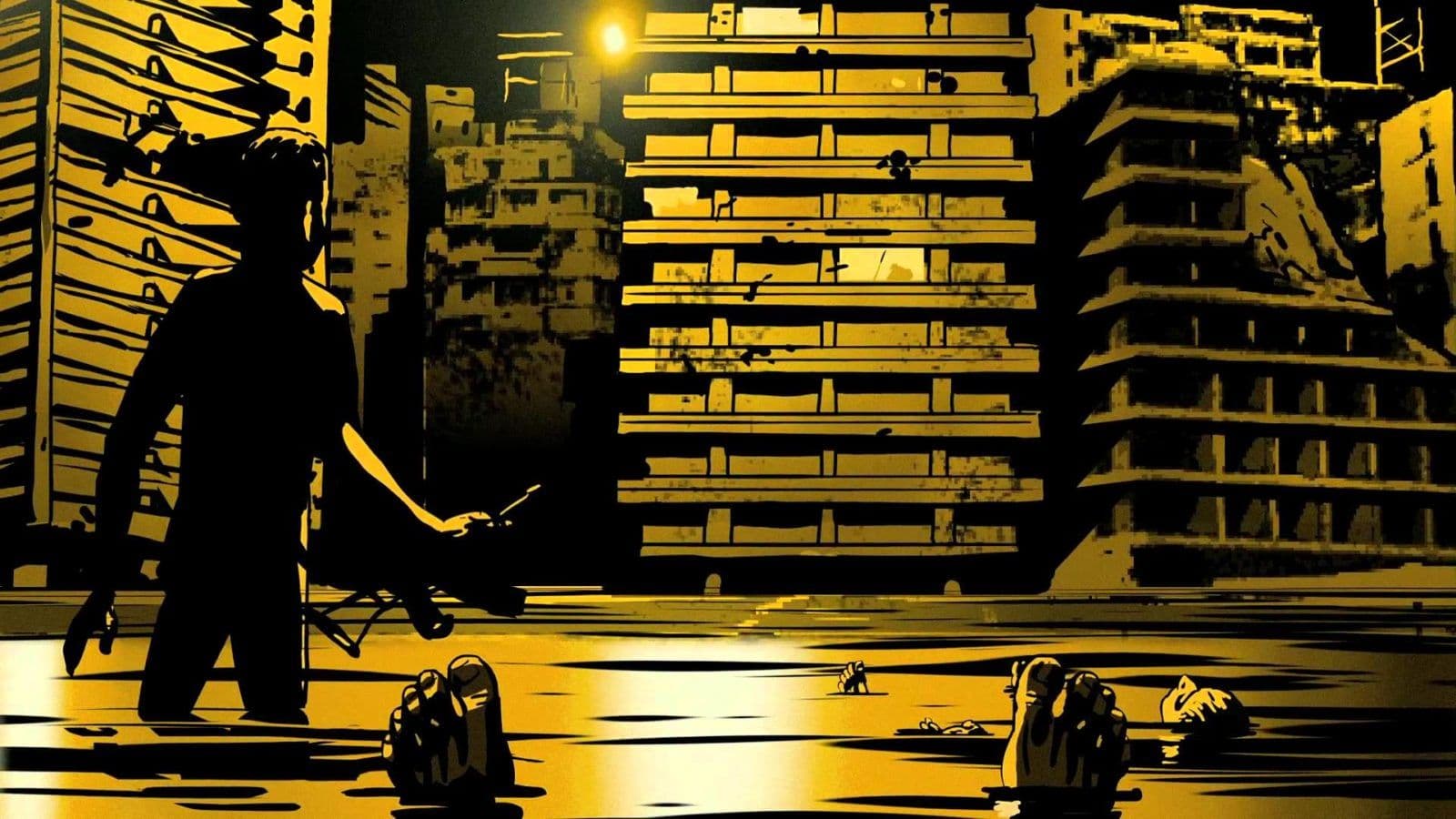

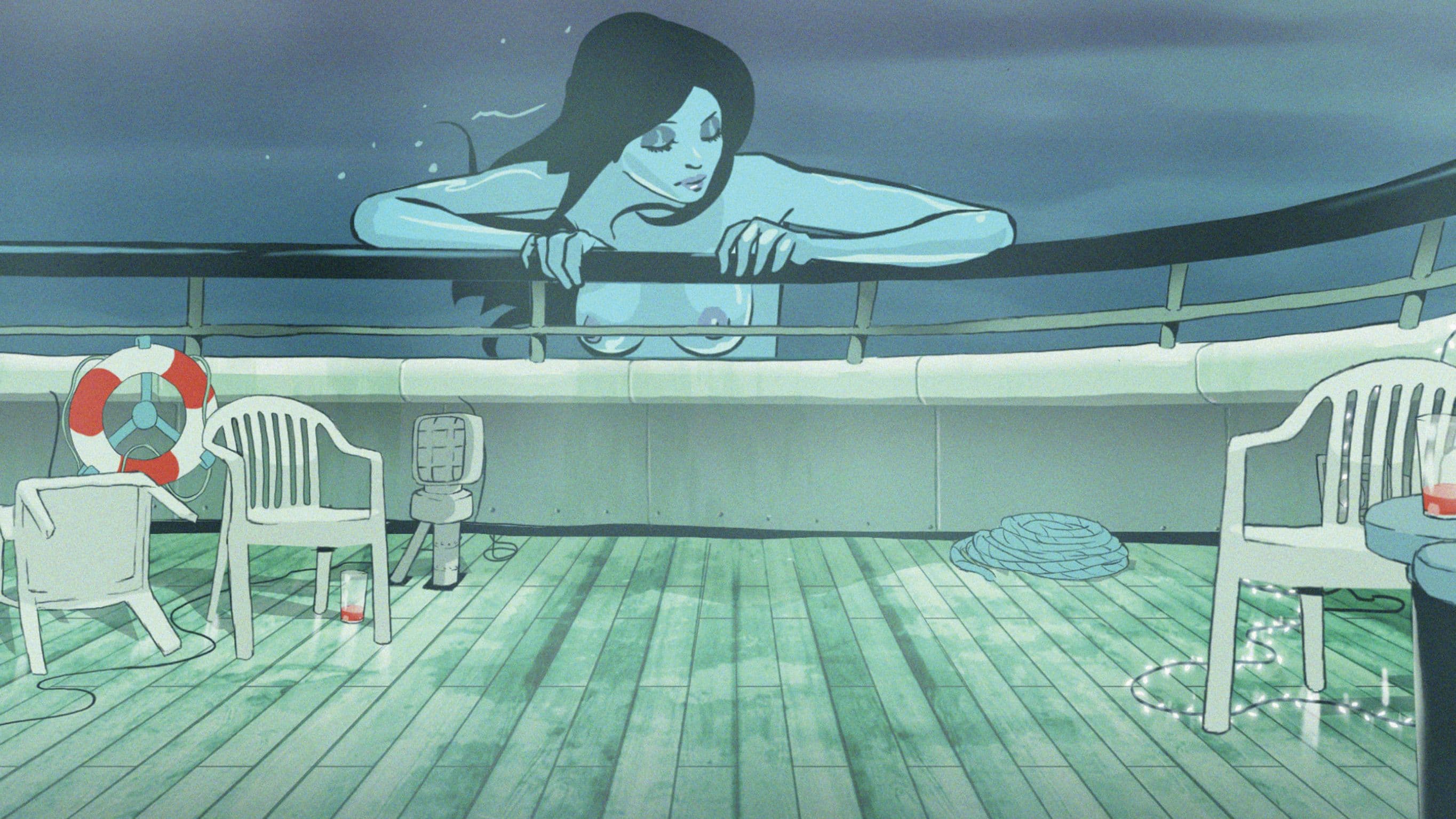

Since the memory of trauma is never realistic, but fragmentary, surreal, and hallucinatory, Folman uses distinctive Flash animation, with its saturated colors and fluid, almost “floating” movements, to give shape to an aesthetic that could be described as metaphysical realism applied to the documentary genre. The function of animation in this work goes far beyond mere aesthetics; it is a philosophical and ethical choice. Folman uses it as a filter of modesty, a way of representing horror without falling into the trap of voyeuristic spectacle that a live-action reconstruction would have risked. But, more profoundly, animation becomes the perfect language for the fallibility of memory. Its inherently subjective nature, every line a choice, an interpretation, perfectly mirrors the state of a traumatic memory: it is not a photograph of reality, but a feverish and hallucinatory reconstruction of it. There are many influences behind this unique visual style. There are echoes of the quasi-rotoscoped fluidity of certain Richard Linklater films, which lends realism to the movements, but the greatest impact seems to come from European graphic novels. The graphic style, with its clean black outlines and flat, saturated colors, is reminiscent of a darker and more politically charged version of the Franco-Belgian “ligne claire,” grafted onto a chromatic sensibility that owes much to Expressionism, where the yellow, sickly lights of the city do not describe a place but a state of mind. It is an art that allows Folman to free himself from the chains of realism to document not the facts, but their tormented echo in the soul. This allows him to visualize the invisible: dreams, nightmares, metaphors. We see a soldier emerging naked from the sea, clinging to the gigantic, maternal body of a woman. We see tanks moving through a landscape that looks like something out of a Dalí painting. And then there is the scene that gives the film its title: a soldier, under enemy fire in a square in Beirut plastered with posters of the assassinated leader Bashir Gemayel, grabs a machine gun and starts shooting wildly, spinning around in a macabre and desperate waltz. It is a hallucinatory “dance of death,” a ballet of bullets and psychosis that captures the madness of war better than any realistic image. It is the terrible beauty that can be found in horror, an aesthetic intuition that runs throughout the film.

But Folman reserves the most powerful and radical cinematic gesture for the finale. After almost ninety minutes spent in the “protected” world of animation, which allowed us to watch the horror through the aesthetic filter of drawing, the director makes a brutal break. The animation disappears and we are thrown into real, chilling footage of the Sabra and Shatila massacre. We see the real faces of women crying, real bodies, lifeless, piled up in the streets. It is a punch in the stomach, a calculated shock that shatters the fourth wall. It is an act of profound ethical responsibility. Folman is telling us: “So far, we have dreamed, remembered, metaphorized. But this, this is not a drawing. This really happened. And its reality is so unbearable that no animation can contain it.” It is an admission of the limits of representation and, at the same time, the strongest affirmation of the need for testimony. Waltz with Bashir not only redefined the possibilities of documentary and animation, but left us with an unforgettable lesson: sometimes, to get to the heart of the truth, you first have to have the courage to walk through the labyrinth of dreams.

Main Actors

Gallery

Featured Videos

Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...