Yojimbo

1961

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

More than just a film, The Challenge of the Samurai, or Yojimbo as universally known by its original title, is a cornerstone, a true foundational myth of modern cinema. An archetype, a film that became a true resource for directors and filmmakers who "plundered" its narrative structure to adapt it to the Western genre (Sergio Leone, for one) or the urban genre (Walter Hill, for another) with "Another 48 Hrs." and "The Warriors" (though more indirectly). Its influence extends far beyond, touching the collective imagination and the very structure of the solipsistic anti-hero, an archetype that from Kurosawa's wandering samurai propagated to the gunslingers of the Old West and the mercenaries of contemporary metropolises.

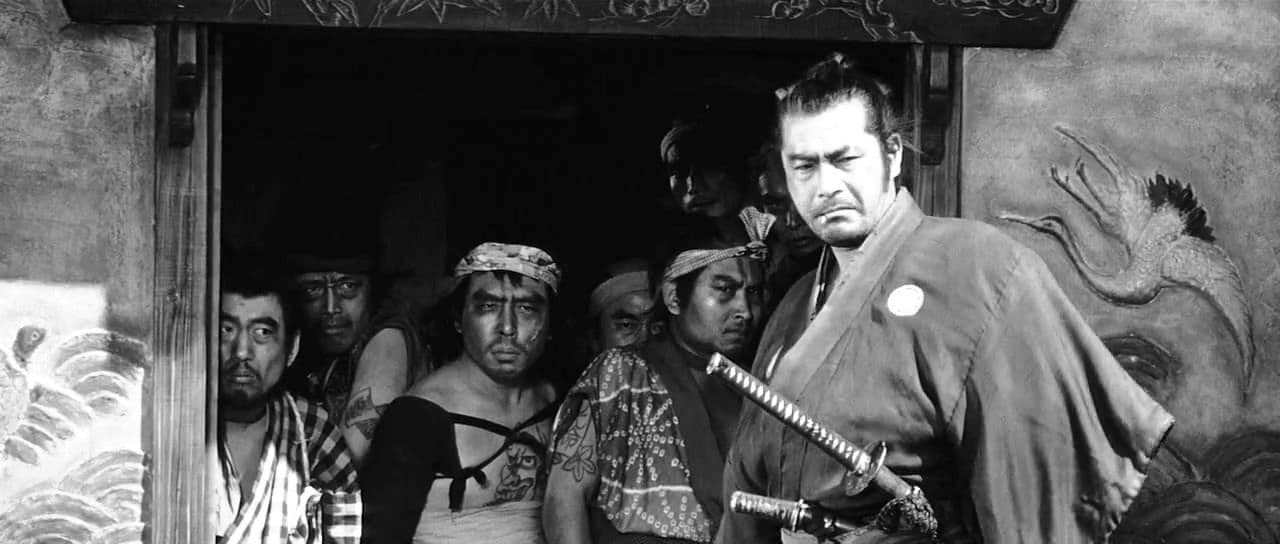

The story centers on the figure of a solitary samurai, Sanjuro (portrayed by Kurosawa's favourite actor, Toshiro Mifune), who, in 17th-century Japan, arrives in a village where a no-holds-barred war is underway between two powerful local families. Mifune doesn't merely portray Sanjuro; he is Sanjuro, with his indolent gait yet charged with explosive potential, his sardonic expression, and the ability to communicate an entire universe of cynicism and, surprisingly, an underlying morality, with a single glance. His performance is a tour de force of stage presence, a monolith of composure and cunning that moves through a world gripped by chaos. His unkempt appearance and apparent indifference conceal a sharp mind and an iron will, making him a complex and endlessly fascinating character.

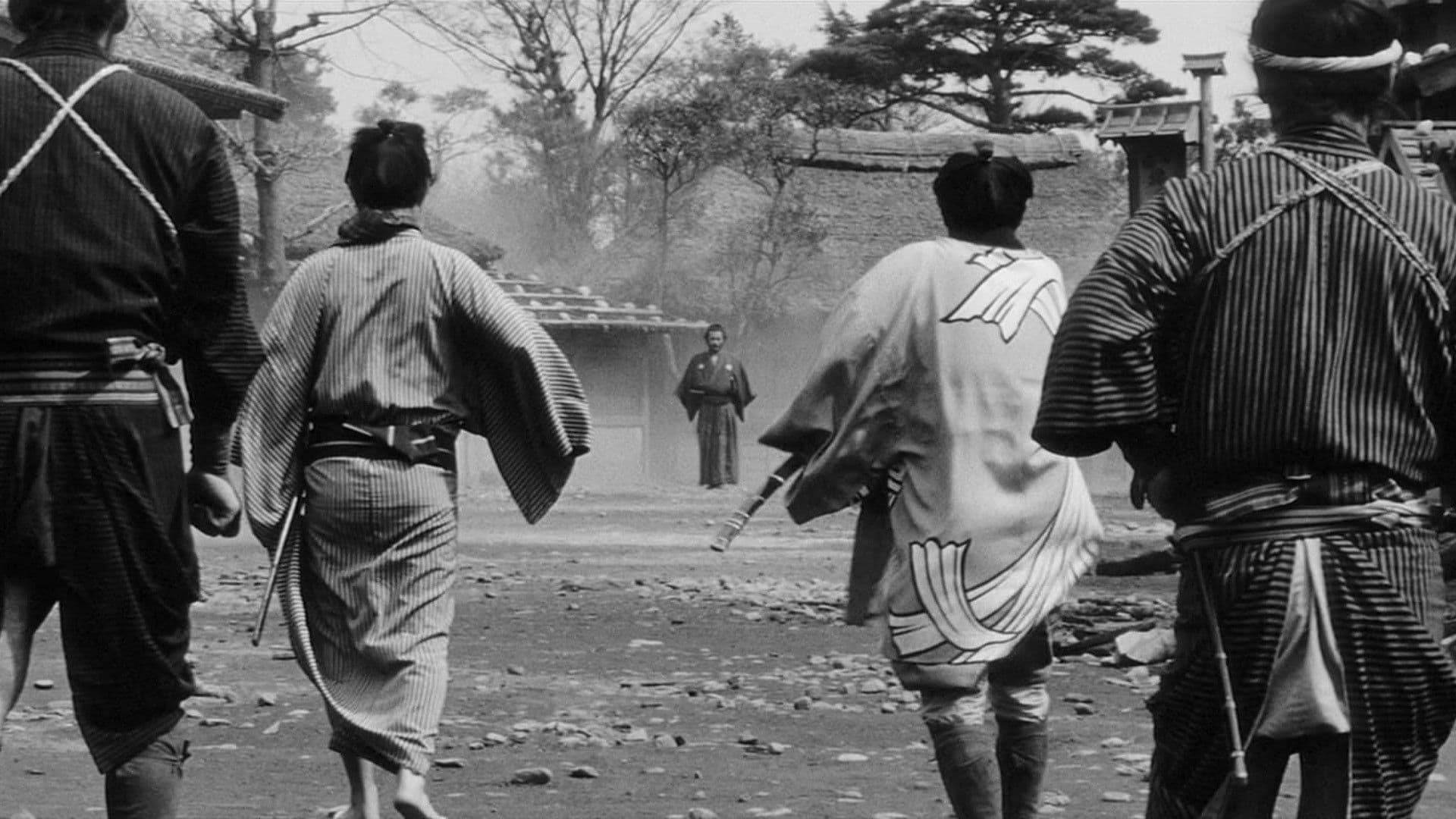

The man will exploit the hatred of the two clans to become the bloody trait d'union between the two contenders, leveraging their lust for power and human corruptibility. The war between the Seibei and Ushitora clans is not merely a backdrop for sword virtuosity, but a ruthless magnifying glass on the endemic corruption that afflicted not only feudal Japan, but human nature itself. Kurosawa, with his usual acumen, paints a microcosm of greed and gratuitous violence, where every gesture is dictated by the thirst for power and terror. This village, once prosperous and now a desolate shell, becomes a metaphor for a society in decay, where order is a faded memory and law is dictated by the sharpest blade. Sanjuro, while operating in this moral quagmire, emerges not as a redeemer, but as a catalyst who, through chaos, re-establishes his own peculiar balance.

His strategy is in fact very simple: to get paid by both factions and to make both believe he is a hitman loyal now to one, now to the other, depending on the contingency. This tactic, seemingly amoral, is the key to his survival and, ultimately, to his subtle form of justice. Sanjuro is not a hero in the conventional sense of the term; he is an opportunist who, by exploiting the weaknesses of others, manages to eliminate the parasites afflicting the village. His morality is pragmatic, almost existentialist, and manifests not through noble proclamations, but through decisive and often brutal actions. He is a man of his time, a masterless ronin, whose only compass is a personal code of survival and disdain for cowardice and pettiness.

There are countless references to this work found in Sergio Leone's cinema: in "A Fistful of Dollars" Clint Eastwood always keeps a hand under his poncho, just like Sanjuro inside his kimono; furthermore, both the samurai and the gunslinger often hold a toothpick in their mouths. But Kurosawa's influence on Leone transcends mere visual details, transforming declared plagiarism into a sincere homage that redefined a genre. It is in the narrative architecture, in the construction of the enigmatic character who arrives from nowhere to disrupt the balance of a pre-existing microcosm, in the management of tension that explodes in rapid and brutal duels, that the true debt lies. Eastwood's "man with no name" is, to all intents and purposes, a transplanted Sanjuro, a ronin of the American plains, whose ambiguous morality is only partially concealed by a brutal pragmatism. Leone did not merely replicate; he distilled Kurosawa's essence, filtering it through the lens of American cinema and his own baroque and operatic aesthetic. After all, Kurosawa himself was an admirer of John Ford, thus creating a fascinating circle of inspiration that united East and West.

In short, it is evident how much Leone owes to this film and how profound his homage to Kurosawa's cinema was. Yojimbo is an action-packed film where narrative linearity and iconographic taste appear inseparable, contributing to create a reference in contemporary action cinema. The narrative linearity of Yojimbo does not diminish its complexity, but rather enhances its power. Kurosawa, a master of mise-en-scène, orchestrates every shot with almost painterly precision, transforming barren landscapes into dramatic arenas and marked faces into maps of suffering and determination. The camera moves with relentless fluidity, capturing the brutal energy of the clashes but also the latent tension in the gazes. The wind raising dust, the gloomy skies, the swift and decisive gestures: everything contributes to forging a cinematic language that would become a vademecum for entire generations of directors, from Sam Peckinpah to Quentin Tarantino (who has stated he drew heavily from Kurosawa's dynamism and stylized brutality), up to the most recent exponents of Korean action cinema, all in some way indebted to Kurosawa's visual ardor and narrative conciseness.

A film that cannot be foregone even to fully understand the creative evolution of today's action movies, all of which are somewhat children of this story, and which continue to reverberate its essence of a solitary and cynical hero, a beacon in the fog of moral ambiguity.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...