Zelig

1983

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

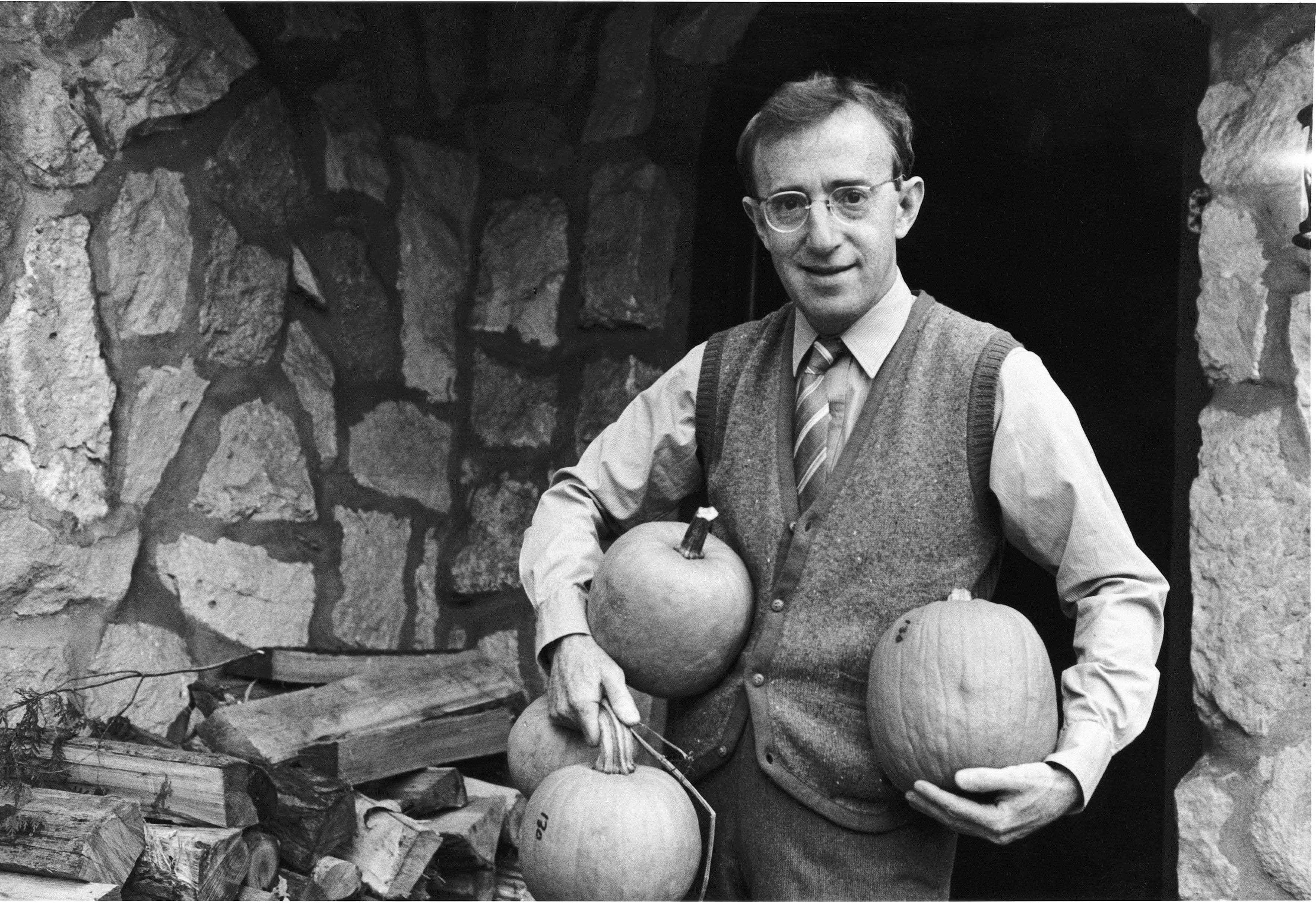

The brilliant and restless Woody Allen grapples with a biographical work shot in documentary form.

Parodic, ironic, delightfully over the top: a film that entertains beneath the serious veneer of a historical document. But "Zelig" is not just a brilliant comedy; it is a pioneering, almost prophetic work in the exploration and deconstruction of the mockumentary genre. Long before films like This Is Spinal Tap or Forgotten Silver solidified the genre in the cinematic landscape, Allen intuited its dizzying potential not only for comedy but also for critique, using it to question the very nature of truth, history, and the media construction of the individual. His mastery lies in manipulating the form with almost scientific precision, elevating parody into a tool for philosophical inquiry.

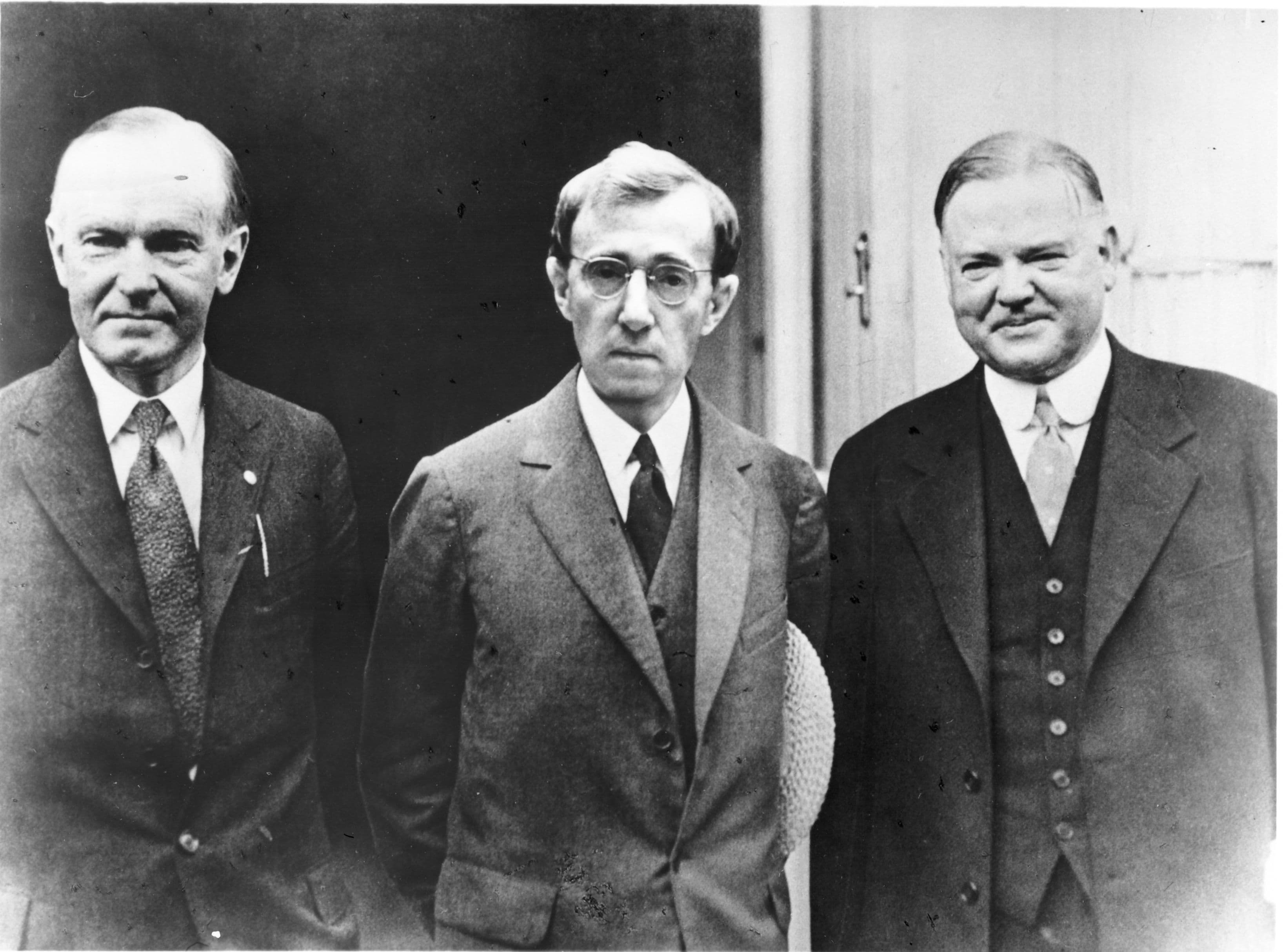

The presence of a narrator describing the protagonist's habits as if they were Darwinian biological phenomena, the dialogue in interview form, the scenes filmed as if they were archival footage: all this contributes to giving this work a pompous and scientific appearance, yet beneath the armor of erudition moves Woody Allen's fierce spirit, lashing human customs and habits with merciless irony. This meticulous emulation of the documentary style of the 1920s and 1930s, from the film grain to the declamatory tone of the narrating voices, is not merely a stylistic device. It is an astute commentary on the malleability of historical narrative, on the media's ability to shape and even invent reality. Allen does not merely make us laugh at academic pomposity; he prompts us to reflect on how easily we accept what is presented to us as "fact" or "historical truth," especially if conveyed with the authority of presumably authentic voices and images.

It is the story of a grotesque character, Leonard Zelig, who in the 1920s becomes famous for his abilities as a human chameleon, perfectly blending with the culture and physical appearance of his interlocutors. He is studied like a laboratory guinea pig by a team of scientists including Dr. Eudora Fletcher, who takes his case to heart, digging deep into Zelig's multifaceted personality. This yields a disconcerting picture of humanity's ability to self-reprogram according to the habitats it is placed in. But Zelig's condition transcends the simple metaphor of social conformity; it becomes a poignant allegory for the loss of identity in an era of massification and pressure to conform. Zelig, with his elusive essence, embodies the existential anguish of the modern individual who, lacking a firm inner core, dissolves into the context, adopting the likeness of what surrounds him just to be accepted. It is the fear of non-being, of not belonging, that drives him to transform from a Jewish doctor to a Hungarian at a Nazi rally, from a Black jazz musician to a white intellectual.

The figure of Dr. Fletcher, portrayed with vibrant intelligence by Mia Farrow, becomes the ethical and scientific counterpart to this deviation. Her empathetic approach and her determination to delve into the roots of Zelig's trauma represent the search for authenticity in a world that seems to reward inauthenticity. Their relationship, imbued with unexpected tenderness, is the emotional heart of the film, a balm for Zelig's restless soul and, by extension, for our own. The psychoanalytic inquiry here is not merely a comedic device, but a serious, albeit satirical, exploration of the subconscious and its frailties. Ultimately, the film is an examination of identity: not what we are, but what we choose to be or what we are forced to become. Zelig's parable culminates, bitterly, in his re-emergence as a public figure, a hero of singularity, only to see him, in the final scene, relapse into his mimetic tendencies in the face of the rise of Nazism. This bittersweet conclusion suggests that, however much the individual may seek their own authenticity, the forces of standardization and collective hysteria – symbolized by the brutality of nascent fascism – are always lurking, ready to suck the self into a dangerous, chameleon-like conformity.

Everything is delightful in this film: the use of a pompous black and white in the style of old BBC documentaries, Dick Hyman's song "Chameleon Days" in perfect 1920s style, the self-deprecating performances of Allen and Farrow. But the "delightful" here also encompasses prodigious technical inventiveness. The reproduction of period black and white, curated with meticulous perfection by cinematographer Gordon Willis – the "Prince of Darkness" known for his chiaroscuro in The Godfather and previous Allen films – is not just a stylistic choice, but a true tour de force. The most arduous challenge was the integration of Allen and Farrow into authentic archival footage from the 1920s and 1930s, an undertaking that required pioneering techniques of superimposition and cinematographic manipulation, making "Zelig" a precursor to the visual special effects we take for granted today. Seeing them converse with real historical figures, or appear alongside Hitler and Mussolini, is a surreal experience that amplifies the parodic genius and critique of media manipulation. No less fundamental is the musical contribution of Dick Hyman, who did not limit himself to "Chameleon Days" but composed an entire score of original pieces in the style of the jazz orchestras and big bands of the era, lending the film an almost disarming sonic authenticity and contributing to that sense of total immersion in the past. The presence of real intellectuals and public figures of the era, such as Susan Sontag, Saul Bellow, Bruno Bettelheim, or Irving Howe, who participate in the fake documentary, further elevates the level of parody, lending credibility and weight to the fiction, and at the same time offering a subtle meta-commentary on the role of "experts" in constructing public narrative.

Ultimately, a cult classic of adamantine purity, in which one transitions from a subdued smile to unrestrained laughter with some memorable lines such as: "I've written many essays on psychoanalysis, I worked with Freud in Vienna. We split over penis envy: Freud thought it should be limited to women." This line, seemingly a simple gag, is in reality the quintessence of Allen's humor: an explosion of intelligence that dismantles the totems of culture, science, and psychoanalysis with corrosive irony. "Zelig" is not just a brilliant comedy or a bold formal experiment; it is a complex and layered work of art, a filmic essay on identity, truth, conformity, and the perennial search for authenticity in a world increasingly prone to mimesis. Its cultural resonance endures, testifying to Allen's ability to grasp, with his usual melancholic acuity, the eternal neuroses of the human soul, clothing them in irresistible comedy and unparalleled stylistic elegance. A timeless masterpiece that, like its protagonist, continues to shift shape in perception, always revealing new facets and meanings.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...