A Day in the Country

1936

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Although it is an unfinished work due to the difficulties Renoir encountered in completing the interior shots, we are faced with an emotional masterpiece that revolutionized the poetic capacity to approach Nature and the sense of Beauty in the history of Cinema. Its tormented gestation, marked not only by adverse weather conditions but also by production problems that extended towards the eve of the Second World War, only intensified its status as a precious fragment, a cinematic memory itself imbued with the transience at the heart of its message. Renoir manages to create a sense of beatitude through carefully composed landscape shots that leaves the viewer in a kind of ecstasy. This is not a mere reproduction of reality, but a true cinematic translation of the Impressionist philosophy that permeated his artistic DNA.

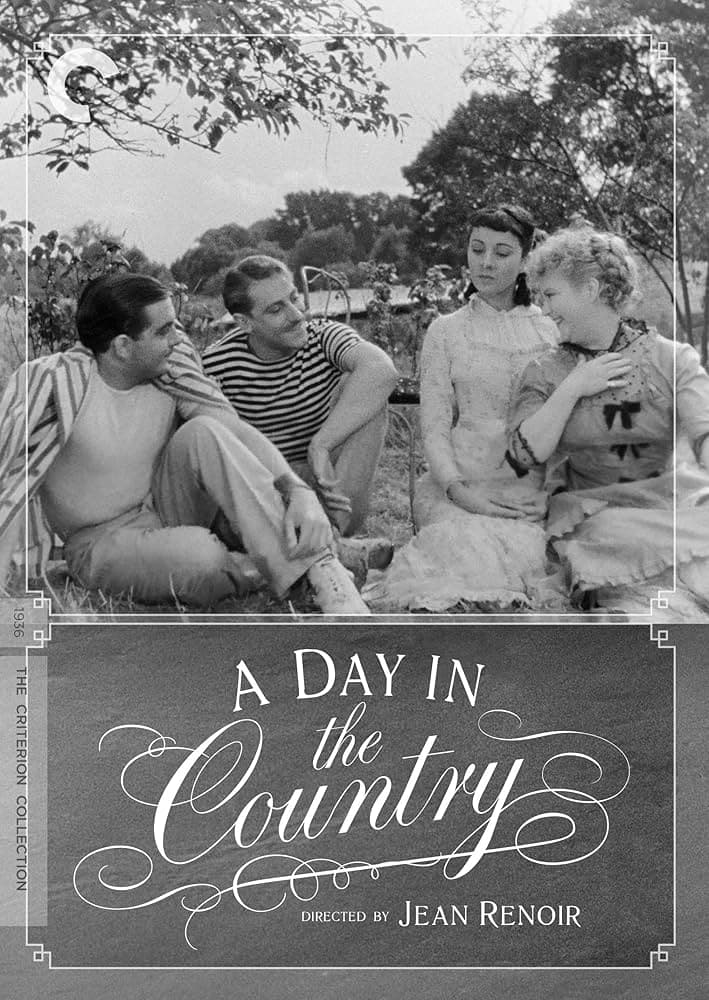

The influence of his father, the painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir, is indeed evident not only in the attention to detail or the composition of images, but in a holistic approach to natural light and color that transforms the screen into a vibrant canvas. Jean Renoir seems to inherit from his father the ability to capture the ephemeral, the vitality of human figures immersed in natural settings, and a predilection for bourgeois leisure atmospheres, as seen in his father's celebrated "Déjeuner des canotiers" (Luncheon of the Boating Party). The light filtering through the leaves of the trees, the reflections on the water, the diffused luminosity enveloping the characters are not mere scenery, but active elements that sculpt emotion, amplify its sensory resonance, and reveal its changeability.

Despite the difficulties encountered during filming, which prevented Renoir from completing the film as he wished – an interruption that, paradoxically, makes it even more akin to its theme of fragmented memory and lost time – "A Day in the Country" retains a unique and timeless charm. The simplicity of the story, adapted from a short story by Guy de Maupassant ("A Country Excursion"), transforms into an ode to life, love, and nature, a delicate and moving fresco on the transience of time and the power of memories. The choice of Maupassant is not coincidental: the master of the short story was also a keen observer of psychological nuances and social dynamics, often with a veil of irony and disillusionment that Renoir masterfully captures and transmutes into lyricism. It is a work that should be savored slowly, allowing oneself to be carried away by the images and emotions, which reminds us of the beauty and fragility of human existence. It is a film that, in its essential narrative minimalism, anticipates the lightness and spontaneity later celebrated by the Nouvelle Vague, and particularly by filmmakers like Rohmer, in their ability to capture the truth of the moment.

The Dufour family, consisting of Mr. Dufour, his wife, their daughter Henriette, and future son-in-law Anatole, goes to the countryside for a Sunday outing. While the men devote themselves to fishing, with a comical clumsiness that reveals their placid bourgeois banality, Henriette and her mother meet two local young men, Henri and Rodolphe. Henriette, captivated by Henri's carefree nature and gallantry, surrenders to a moment of joy and freedom, swinging on the swing and walking with him along the river. The encounter culminates in a passionate kiss, a moment of abandon that will forever mark Henriette's life. Years later, Henriette, now married to Anatole, returns to the same place and relives the memories of that unforgettable outing. The casual encounter with Henri, now aged and disillusioned, makes her realize the passage of time and the ephemeral nature of happiness. The melancholy of the ending is not a judgment on life, but an acknowledgment of its inevitable current, a bittersweetness that permeates the soul of the film.

The plot, though essential, is rich in nuances and emotions. Renoir delicately captures the characters' feelings, their joys, their disappointments, their hopes. Love, passion, nostalgia, and regret intertwine in a poetic and melancholic narrative that speaks to us of life and its ineluctable flow. His aesthetic sensibility for Nature, as mentioned, plays a fundamental role in the film. Renoir invites the viewer to contemplate Nature, using long takes and slow, fluid camera movements, which allow the eye to wander and linger on details, as in a painting. This attention to time and duration would profoundly influence later filmmakers, particularly Andrei Tarkovsky, who in his films creates a slow and meditative rhythm, allowing the viewer time to immerse themselves in the images and reflect on their deeper meaning. While Renoir celebrates a more sensual and immanent nature, a mirror of human emotion in its immediacy, Tarkovsky elevates it to a spiritual and metaphysical dimension, yet both share the conviction that landscape is not mere background, but a silent and revealing protagonist.

In Renoir's film, Nature is not just a background, but an active element that reflects the emotions and moods of the characters. The flowing river, the trees swaying in the wind, the light filtering through the leaves, all contribute to creating a lyrical and melancholic atmosphere, in harmony with Henriette's feelings. It is nature that becomes an accomplice to the ephemeral idyll, framing the beauty of the fleeting moment, but it is also nature that bears witness to its inexorable fading. Tarkovsky, in his films such as "Solaris," "The Mirror," and "Nostalghia," embraced this idea, using Nature as a means to explore the human psyche and its depths, often in dialogue with architecture or ruins, to express a sense of loss or existential quest.

The close-up of Henriette swinging on the swing, filmed slightly from below to emphasize all her grace and charm, is a directorial masterpiece of bold and pioneering cinematography. The camera, boldly affixed to the swing, conveys the dynamism of the movement and Henriette's ecstatic expression, immersing the viewer directly in her experience of freedom and pure joy. This choice is not only revolutionary for its time – challenging the conventions of a cinematography still often static and theatrical – but it is also an expressive choice that elevates the moment to a universal symbol: the physicality of movement merges with emotional liberation, the giddiness of the swing with that of surrendering to desire. It is a moment that encapsulates the very essence of youth and its ability to live the instant absolutely, unaware of the consequences of time. Its modernity is disarming, an anticipation of those immersive techniques that would only become common decades later.

A film that continues to move and provoke thought, a work that reminds us of the importance of savoring every moment of life and treasuring memories, especially the gentler and more painful ones, for it is they that define the trajectory of our soul.

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...