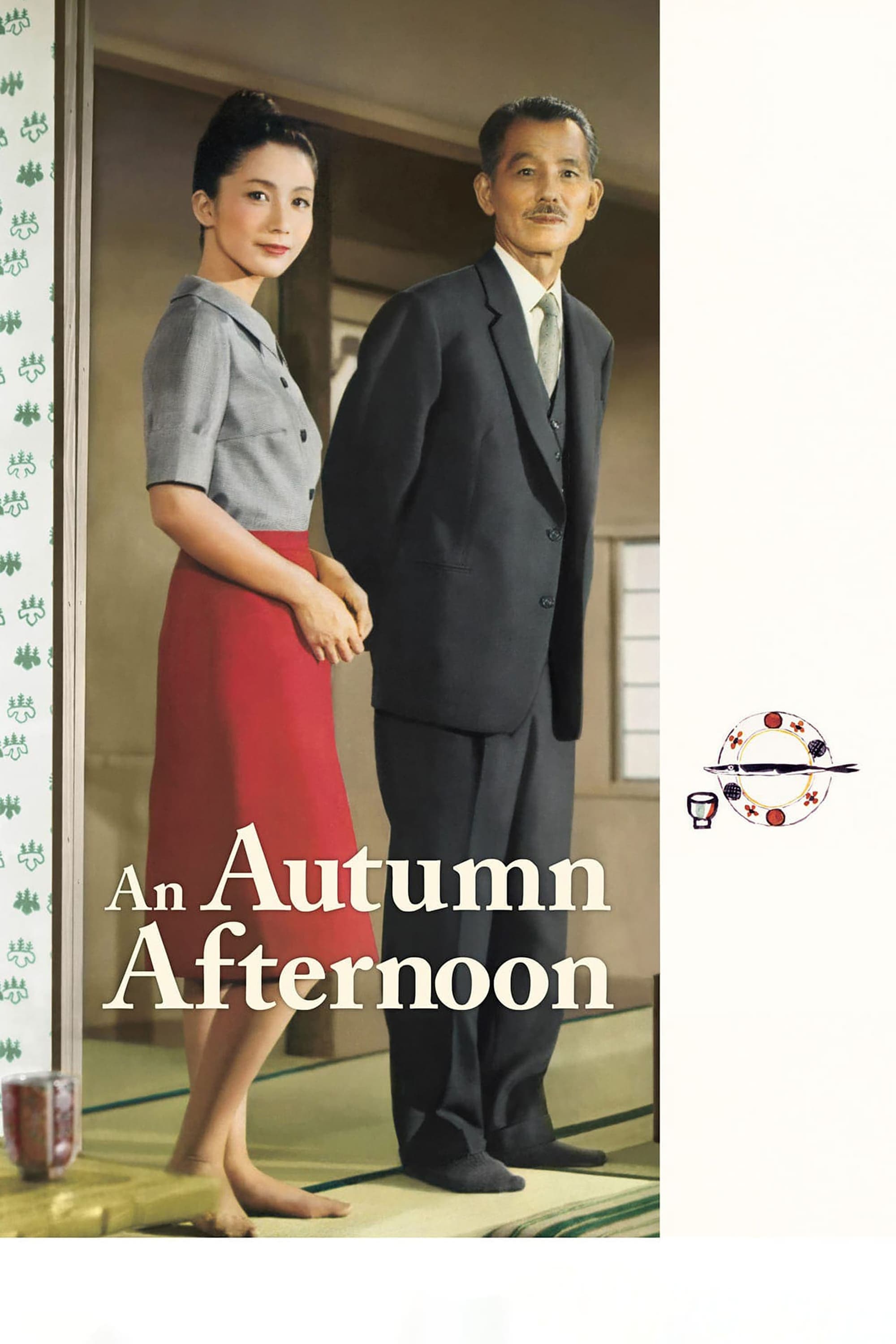

An Autumn Afternoon

1962

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

In his last film, Ozu revisits the story of Late Spring and repaints it with the colors of a "melancholia" that here, in the twilight of his work, takes on the definitive contours of a farewell, not only to his audience but to an entire world slipping away. If the 1949 masterpiece was imbued with an almost raw pain for leaving the nest, in An Autumn Afternoon (the original title, Sanma no Aji, the taste of autumn saury fish, far more evocative, evoking the ephemeral and the cyclical), the sadness becomes more mature, distilled, permeated by that ineluctable mono no aware, the melancholic awareness of the impermanence of things.

The story introduces us to Hirayama Shūhei, a widower living in the industrial area of Kawasaki with his twenty-four-year-old daughter, Michiko. A man immersed in a comforting routine, between the walls of his home and evenings with old friends, drinking companions and regrets. But time in Ozu is never static; it is a slow and inexorable river. Hirayama realizes that Michiko needs to leave the nest and build a life away from him, an imperative dictated not by selfishness but by a deep sense of paternal duty, which compels him to give up his daily source of comfort. Despite his moral rigor – a mask of dignity and self-sacrifice – he will try by every means, often indirect and subtly painful, to convince the girl to leave him. In Ozu, there is no shouted drama, but the slow trickle of necessary decisions, accepted with the silent grace of one who understands the order of things.

The past becomes a borderland teeming with monsters of memory: the ghost of his lost wife, the solitude that awaits, the memory of a professor, now a human wreck, who kept his daughter with him until she became old and undesirable. This specter of the future, somber and admonishing, is what drives Hirayama to action. The future, in contrast, presents itself as an uncertain and hazy option towards which one must daringly reach out, an act of courage necessary not so much for himself as for the happiness of others. A hope of continuity – more than rebirth, in the Western sense of the term – hovers over everything, with a desperate lyrical breath that reaffirms its pulse and silently draws it towards our hearts. Ozu does not promise a radiant dawn, but the acceptance of the night that follows the day, an eternal cycle of arrivals and departures.

The poetics of small things, a kind of elegy that powerfully rises from everyday life, irremediably fascinates this director and informs his entire oeuvre. It is in the ritual of shared sake, in walks along back roads, in the sparse yet incredibly dense dialogues, in the "pillow shots" – those frames of inanimate objects or urban landscapes that serve as meditative intermezzi, almost a breathing pause between one scene and another – that his art reveals itself in its fullness. The camera, fixed and positioned at tatami height, places us at an intimate observation level, as if we were participants in the scene, never intrusive but always present. It is a stylistic choice that reflects a philosophy: life is not made of exceptional events, but of the sum of infinite ordinary moments. Even the use of color, inaugurated by Ozu in his final phase, is never garish or symbolic in a Western sense; rather, it accentuates the understated beauty of reality, the vivid reds of sake boxes or clothes that punctuate the uniformity of life.

The characters, played by actors who have appeared throughout the Master's entire filmography, such as the ever-present Chishū Ryū in the role of the father, are not just narrative figures but archetypes confronting the transformations of post-war Japan. The conflict between tradition and modernity, between duty and individual desire, underlies every gaze, every silence. Evenings at the bar with friends, reminiscent of a lost youth and vanished ideals, are moments of catharsis and bitter reflection, where sake is not just a ritual, but an anesthetic for the soul, a merciful veil over impending loneliness.

An Autumn Afternoon is not only his last film but a long farewell journey for the Master, a long subdued poetic song left as a testament. He would die little more than a year after its release, on his sixtieth birthday. It is a work that condenses and sublimates his thematic obsessions, his unmistakable cinematic grammar, his compassionate but unyielding gaze on the human condition. It is a precious gift to be treasured, a distillate of wisdom and melancholy that reminds us of the ephemeral beauty and dignity of life in its most unvarnished everydayness. Ozu confirms himself, with this concluding masterpiece, as a giant among the giants of the Seventh Art, a poet of silence and human feeling who, like the lingering taste of sake, leaves an indelible echo in the soul.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...