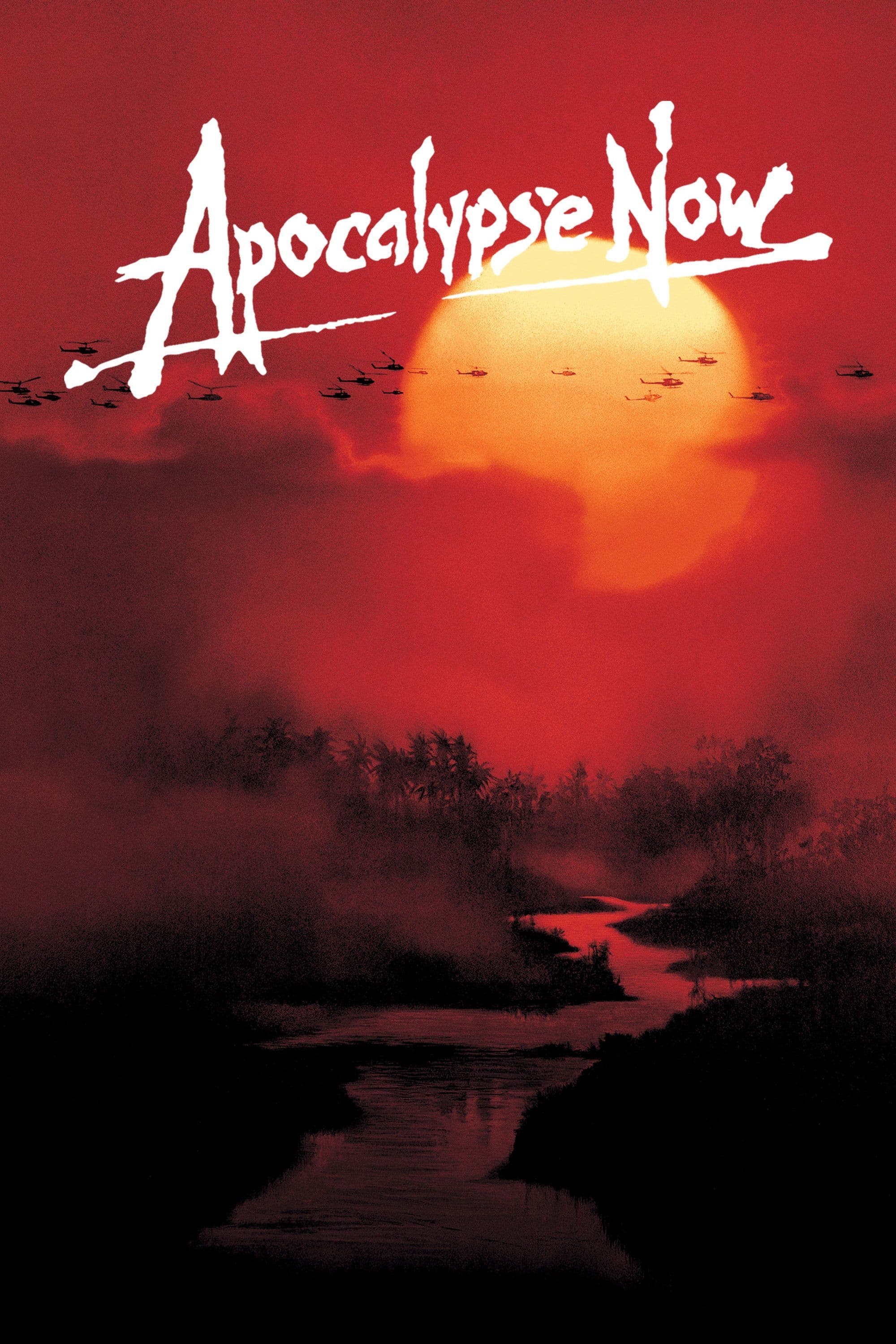

Apocalypse Now

1979

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(2 votes)

Director

The film recounts the initiatory journey of a young officer in war-torn Vietnam, a metaphysical odyssey that rips the veil of sanity to plunge into the abyss of the irrational, a distorted mirror of a fractured America and its post-war disillusionment. Indeed, as he travels up the Nung River, Lieutenant Willard is tasked with assassinating Colonel Kurtz, a U.S. Army officer who has proclaimed himself a warlord and become an unstable leader of an army of cutthroats rampaging through the northern part of the river, carrying out raids and devastation. The mission assigned to Willard is more than a mere execution: it is an assignment that destines him to confront the extreme limits of human experience, with the collapse of civilization and the emergence of a primordial, unstoppable horror.

As he journeys up the river, Lieutenant Willard will witness firsthand the absurdity of that sideshow they call war. The greenish hell of Vietnam reveals itself not only as a theater of death, but a stage of Beckettian absurdity, where military logic dissolves into an unbridled delirium. Forgotten outposts teeming with senseless violence, drugged soldiers defying death with the recklessness of the damned, nocturnal parties amidst the glare of explosions like a lysergic hallucination orchestrated by chaos: officers burning villages with women and children, spraying Napalm from helicopters hovering to the rhythm of the Ride of the Valkyries, surfing soldiers riding waves under bombardments, civilians massacred during simple checks just because a girl made a sudden movement. It is a world where horror is not only physical violence, but the complete disintegration of reason, a sideshow of freaks where every logic is subverted and existence itself is a macabre farce.

This descent into hell was no less real for Francis Ford Coppola and his crew, whose production epic in the Philippines has become legendary, an odyssey as feverish and mad as the one depicted on screen. Amidst devastating typhoons, actors' health problems – Martin Sheen's legendary heart attack – and the continuous pressures of a gigantic, out-of-control production, the film itself became a simulacrum of war, an incessant struggle against entropy, where reality blurred into creative delirium, and the director's obsession merged with that of his characters. Such an immersive process that even Martin Sheen confessed to feeling, at times, like Willard.

When the lieutenant comes face to face with Kurtz, he will succumb to his dark charisma but will not waver from his mission. In that gloomy sanctuary of death and philosophy, Willard and Kurtz confront each other in a dialectical and spiritual duel, where the allure of barbarism and the logic of destruction contend for the protagonist's soul. A torrential, mystical, dark film, in which Vittorio Storaro's cinematography and Walter Murch's editing create a hallucinatory and oppressive atmosphere, almost an acid trip into the collective unconscious.

A performance of the highest caliber for both protagonists: Martin Sheen, whose performance is imbued with a palpable existential anguish, and Marlon Brando, who, despite his weight and eccentricities on set, delivers a monolithic, almost sculptural interpretation that has indelibly marked the collective imagination.

Some scenes belong to the memory of every devotee of the seventh art, not mere sequences but epiphanic moments that transcend narration to become symbols. One above all: the aforementioned Ride of the Valkyries, a symphony of destruction choreographed to the sublime Wagnerian melody, is not just an iconic sequence; it is a programmatic manifesto. There, in the whirring of the Apache helicopter blades hovering laden with napalm, the colonial arrogance and blind fury of a superpower imposing its will with an almost operatic aesthetic violence are condensed. Robert Duvall's mocking and Mephistophelian smile, in the role of Colonel Bill Kilgore, and his famous line: “I love the smell of Napalm in the morning,” crystallize the moral apathy and proud ignorance of those who have embraced horror as a second skin, transforming it into a bizarre fetish of virility and power. This sequence, an apotheosis of war Kitsch, elevates brutality to the sublime macabre, making it an experience as visceral as it is intellectual, a perfect example of how Coppola subverts expectations and challenges the audience to confront the distorted beauty of war.

Kurtz's character is naturally the narrative keystone of the entire story, just as he is in Joseph Conrad's novel Heart of Darkness, from which the film is inspired and which John Milius filtered into the screenplay, transposing fin de siècle colonialist anguish into a parable on post-Vietnam trauma. Kurtz is a kind of war Totem, embodying all the horror that the wartime event brings with it; he is somewhat corrupted by it but retains his own distorted rationality. His mind is a labyrinth of lucid madness, a library of thoughts that have crossed the boundary of conventional humanity. The shots of Kurtz, all in semi-darkness, shrouded in a darkness that precedes and follows him, depict him as a kind of philosopher corrupted by the surrounding gloom, an oracle of an inner apocalypse. This visual choice is not accidental: it hides the monster, but amplifies its psychic presence, suggesting that his influence is more an idea, a mental virus, than a physical person. He is a Kurtz who has gazed into the abyss and, finding it empty, decided to fill it with his own terrifying logic.

The horror unleashed in the country has ancient roots and is inherent in man, a theme that Kurtz's final monologue, the philosophical apex of the film, explores with disarming brutality. «I have seen horrors, horrors that you have seen too. But you have no right to call me a murderer. You have a right to kill me, yes, but you have no right to judge me. There are no words to describe what is strictly necessary to those who do not know what horror means. Horror has a face and you must make a friend of horror. Horror and moral terror are our friends. If not, then they become enemies to be feared. They are the true enemies…». These words are not just a justification, but a shocking revelation: Kurtz is not just any madman, but a man who, having probed the depths of human depravity, has understood that the only way to survive – or to dominate – in that chaos is to embrace horror itself, to befriend it, to integrate it into one's own psyche. He proposes a twisted but irrefutable logic, a radical critique of bourgeois morality incapable of understanding the true nature of conflict, barbarism, and the human condition when the scaffolding of civilization collapses. His assassination by Willard is not merely the execution of an order, but a sacrificial rite, a desperate attempt to extinguish a flame that burns in every dark corner of the human soul, knowing, however, that the spark, once ignited, is destined to spread.

Francis Ford Coppola thus succeeds in the endeavor of documenting this horror and transforming it into art, gifting us a cornerstone of modern cinema, a titanic work that stands as a monument to the madness and grandeur of the "New Hollywood Cinema". Without judgment, without false pretenses, without rhetorical artifice: only great cinema, capable of questioning the roots of evil and the fragility of civilization with a visual and intellectual power that still resonates today with the force of a distant, but inexorable thunder.

Main Actors

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...