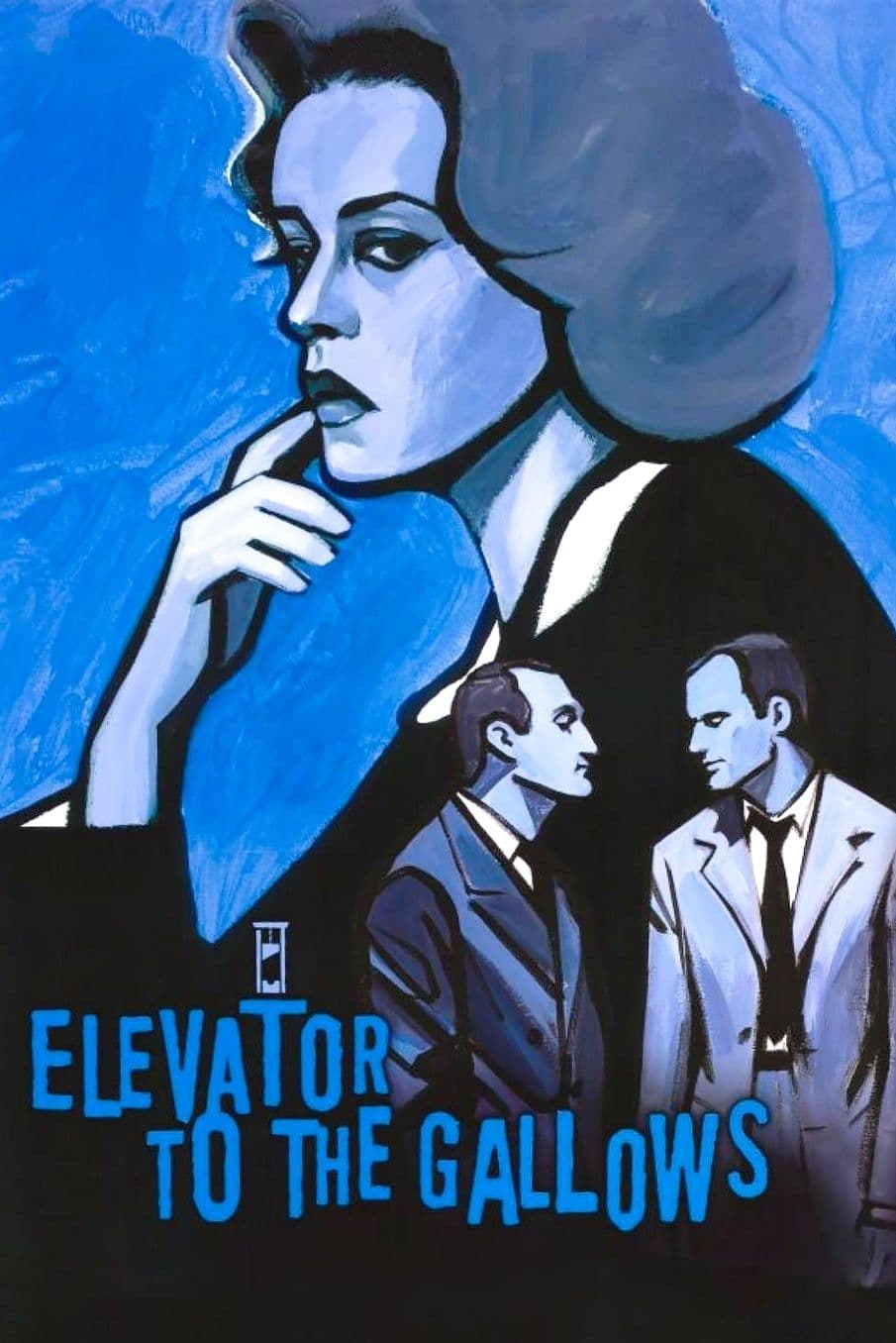

Elevator to the Gallows

1958

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Louis Malle is a man who navigates the subtle boundary separating shadows from emotional night. And it is no coincidence that his debut film, that admirable essay on fate and alienation which is Ascenseur pour l'échafaud, opens with a twilight that is as atmospheric as it is spiritual, a prelude to the descent into the heart of darkness of the human psyche and the moral underbelly of the City of Lights.

In this great film, the director dwells on the most turbulent passions and the darkest facets of the human soul, revealing the cracks in the facade of an apparently impeccable bourgeois society. The vision that emerges is never a realism for its own sake but is almost an ontological mirror in which events are transfigured and acquire the character of a mild drama. A drama that does not scream, that does not revel in explicit melodrama, but whispers with an unsettling clarity the existential implications of every choice, every chance occurrence, every mistake. Malle, with almost surgical precision, unveils the fragility of human will in the face of the absurd, which manifests here not as a catastrophic event, but as a sequence of unfortunate and trivial mishaps that chain together the destinies of his characters. Indeed, while rooted in the canons of classic noir, the film distinguishes itself through an intense focus on interiority and the indifference of fate, anticipating that groundbreaking cinema which would soon be codified as the Nouvelle Vague.

Jeanne Moreau plays the role of a dark lady, Florence Carala, who convinces her lover, Julien Tavernier – a former Foreign Legion paratrooper, now a shady arms dealer for whom her husband works – to kill her inconvenient spouse. Her Florence is not the classic one-dimensional femme fatale of American noir; she is rather a tormented soul, a figure of an icy yet poignant beauty, whose iconic nocturnal wandering through the streets of Paris, under the dim lamplight, becomes a desperate ballet of anxiety and foreboding. Her inner voice, which guides us through her obsessive search for Julien, reveals a palpable vulnerability, an agonizing wait that makes her infinitely more complex than a mere instrument of evil.

The two plan the murder down to the smallest detail and execute it, only to realize they have forgotten something at the crime scene. It is here that the perfect murder mechanism jams, not due to a brilliant counter-move by justice or an act of betrayal, but due to the most trivial of distractions: Julien, after eliminating Florence's husband, forgets a rope at the crime scene. And it is in the attempt to retrieve it that the engineer of fate finds himself prisoner of the most prosaic of unforeseen events: when the elevator that should lead him to safety gets stuck, not only does a true journey through terror begin, but also a symbolic descent into his own existential prison. The elevator becomes a vertical coffin, a mechanical limbo that isolates Julien from the outside world, forcing him to confront his own isolation and despair.

In parallel, the Parisian night unfolds with a poetic rawness through the camera of Henri Decaë, the cinematographer who would help define the aesthetic of the Nouvelle Vague. His use of natural light, the "candlelight" night shots, the intense chiaroscuro that envelops the figures in a veil of mystery and fatality, are not merely stylistic choices, but narrative elements that amplify the sense of precariousness and alienation. Paris is a silent protagonist, an accomplice and indifferent city that impassively witnesses the drama unfolding in its alleys and Boulevards. The story in which love, death, doubt, and violence intertwine and become indistinguishable, in a crescendo of misfortune that is breathtaking in its inescapability. The obsessive love between Florence and Julien is tinged with shadow and despair; the violence of the murderous act generates a wave of doubt and a series of uncontrollable consequences that, by also drawing in two carefree young people involved purely by chance in a car theft, manifest as the true tragic engine of the film.

A masterpiece of transalpine cinema not only for its acute psychological analysis and its avant-garde aesthetic, but also and above all enhanced by Miles Davis's original soundtrack, written specifically for this film. Legend has it that Davis improvised the entire score in a single night session in December 1957, watching scenes from the film projected onto a screen and allowing himself to be inspired by the atmosphere. His cool, melancholic, and rarefied jazz, with the solitary trumpet weeping blue notes over nocturnal Paris, is not a mere musical accompaniment, but an essential narrative element, a non-verbal voice that amplifies the anxiety, loneliness, and disillusionment of the characters, making Ascenseur pour l'échafaud an unforgettable synesthetic experience, a pinnacle of fusion between image and sound that continues to resonate powerfully decades later.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...