Barry Lyndon

1975

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

Kubrick's tenth cinematic effort, it is based on William Makepeace Thackeray's novel, "The Memoirs of Barry Lyndon," a masterpiece of 19th-century picaresque literature which the New York director transformed into one of the most incisive and, paradoxically, cold examinations of human destiny and social mobility.

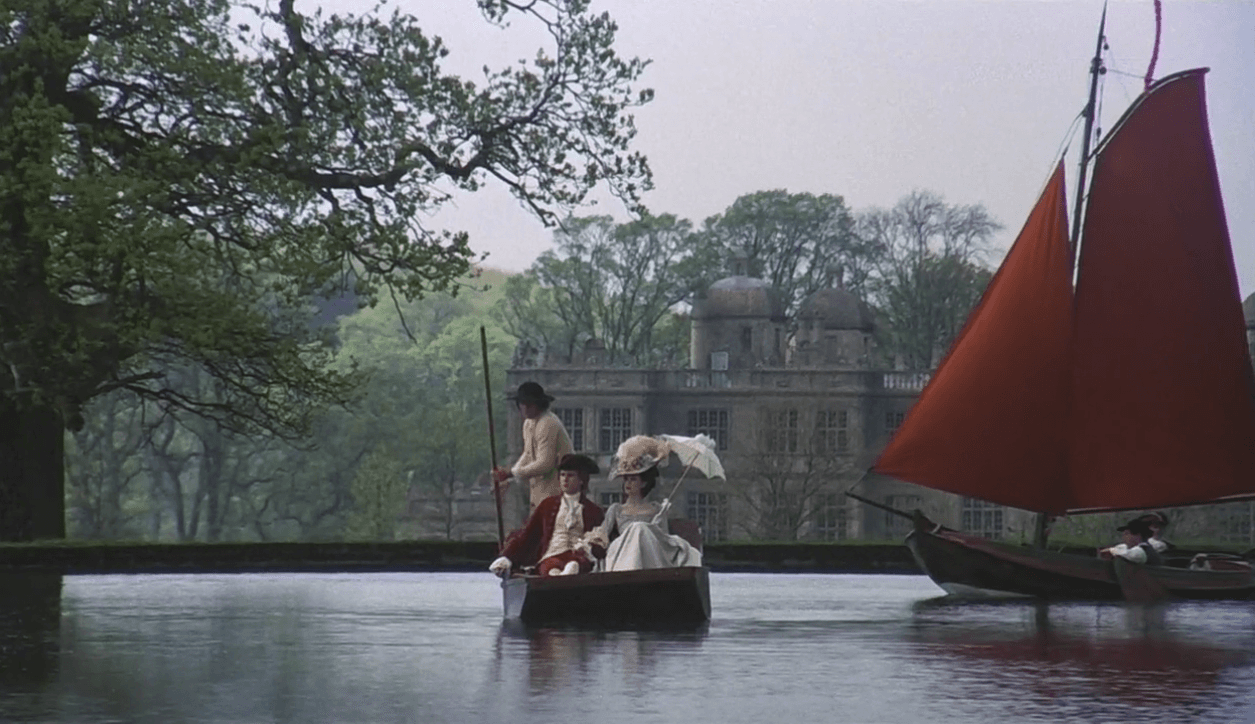

Filming took place in Ireland, Germany, and England and spanned two years, a timeframe that proved indispensable for capturing the essence of an era with almost maniacal precision. Kubrick undertook a meticulous, to say the least, effort regarding locations, sending his collaborators around the United Kingdom, collecting a vast archive of photographs over three years to evaluate every single potential filming site. This dedication translated into a visual fidelity that transcended mere historical reproduction, imbuing the film with an almost tactile dimension, a materiality of the era.

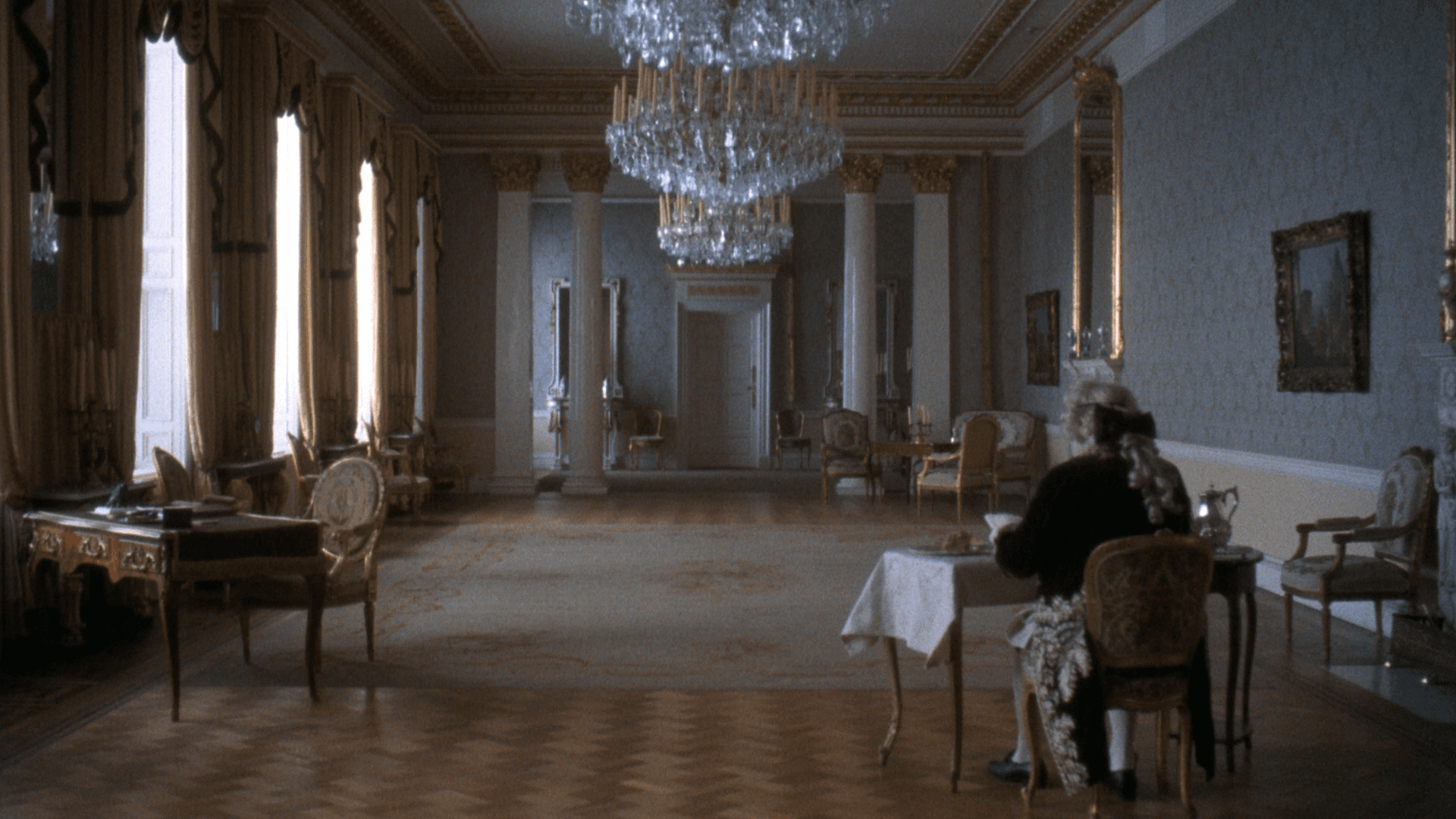

Furthermore, and this is where one of the film's most audacious and iconic innovations lies, Kubrick decided to shoot interiors using only natural light, and to achieve this project, he had special lenses built with glass developed for NASA – the legendary Zeiss Planar 50mm f/0.7, originally developed for Apollo space photography. This choice was not merely a technical display, but a profound aesthetic statement: it allowed scenes to be lit by candlelight, replicating the luminous atmosphere of 18th-century paintings. The result is a visual palette of breathtaking beauty, where every shot emanates the softness and depth of Flemish or Dutch masters — consider the delicacy of light in Vermeer's paintings or the chiaroscuro drama of Georges de La Tour, or indeed the portraits of Gainsborough and Reynolds, which seem to come to life on screen. This audacious and highly risky technique cemented "Barry Lyndon"'s reputation not only as a historical film but as a visual work of art in its own right, a gigantic iconographic repertoire where every single frame appears to be a pictorial masterpiece.

Finally, consider the meticulous research conducted on the costumes, overseen by Oscar-winning Milena Canonero and Ulla-Britt Söderlund, on iconographic sources, on the gestures and etiquette of the era, on the historical period in its entirety, and you will have the measure of one of the most beautiful historical films ever made. This obsessive attention to detail is the cornerstone of a total immersion into the Age of Enlightenment and the Rococo period, a world of crinolines, powdered wigs, and duels of honour. This result, as Kubrick often stated, was achieved thanks to a great team effort of which Kubrick was particularly proud, acknowledging the fundamental contribution of every single department in constructing such a vivid and convincing illusion.

With Barry Lyndon, Kubrick confronts 18th-century England, narrating the exploits of an Irish wanderer who strives by all means to become a nobleman, via duels, wars, and wealthy widows yearning for his young body. It is an era of rigid hierarchies and nascent ambitions, where social ascent is a cruel and often disillusioned game. The film is divided into two parts: in the first, we witness Barry Lyndon's rise and how he manages to achieve power and wealth; the second details his decline and misadventures throughout Europe. This bipartite structure, almost classical in its depiction of fortune and misfortune, is commented upon with detachment by an omniscient narrator, who anticipates events and underscores their relentless fatalism, in a tone reminiscent of Thackeray's own ironic and disillusioned voice.

The character is clearly an anti-hero, ultimately a cynical and ruthless man, glacial in his affections except for his love for his son. Barry is not an agent of action in the traditional sense; he is rather a passive opportunist, a splinter adrift in the great river of history, who adapts and survives more by luck than by intelligence or virtue. Unlike other Kubrickian protagonists, often driven by a lucid madness or an obsession that leads them to destruction (like Alex in "A Clockwork Orange" or Jack Torrance in "The Shining"), Barry lacks true psychological depth, almost a mirror of the social conventions he attempts to break. His sole, true vulnerability is his affection for his son Bryan, a love that will prove to be his ultimate undoing.

A film stylistically pure and perfect as a snowflake, a gigantic iconographic repertoire where every single frame appears to be a pictorial masterpiece. This impeccable visual mastery is complemented by an unforgettable soundtrack, composed predominantly of classical pieces that do not merely serve as a backdrop but become an integral part of the narrative, commenting, ironizing, or amplifying the drama. Franz Schubert's Piano Trio No. 2 in E-flat Major, in particular, becomes the leitmotif of Barry's melancholic destiny, its poignant melody pervading key sequences and imbuing them with a gravity and emotion that the narrative's coldness would otherwise not allow.

While in other Kubrick works the dreamlike or psychological dimension held strong significance, sometimes managing to overpower the action, in "Barry Lyndon" the epic scope overwhelms any psychologism. We are not here to delve into the depths of Barry's mind, but to observe his journey through a cruel and indifferent society. The succession of events is what most concerns the director and, ultimately, the viewer, eager to know the protagonist's fate, in a narrative that almost aligns with that of a historical chronicle, emphasizing the inexorability of time and circumstances. It is a work that invites aesthetic contemplation and reflection on the ephemeral nature of fortune, an epic of vain ambition that, with its glacial beauty, continues to enchant and prompt reflection on the comedy and tragedy of the human condition.

Genres

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...