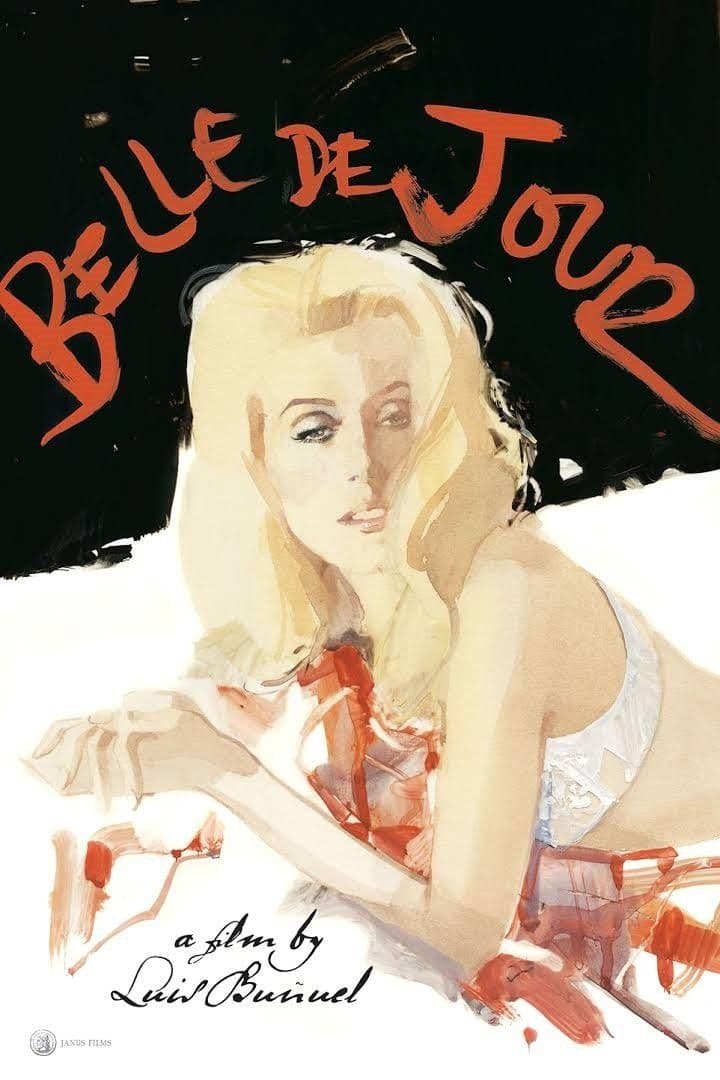

Belle de Jour

1967

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Buñuel’s journey within the troubled nexus of spirituality and corporeality, begun with Viridiana, continues and here reaches its hermeneutic culmination. An obsession, that of the Aragonese master, which permeates his entire filmography, unraveling amidst the intricacies of bourgeois morality and the deepest impulses of the human soul. Where Viridiana explored the corruption of sanctity through innocence devoted to martyrdom, Belle de Jour overturns the paradigm: here it is the most icy worldliness that seeks redemption, or at least authenticity, through the most audacious transgression. It is the paradox of purity that stains itself to discover its own essence, a profane ritual that unmasks the hypocrisies of the sacred.

This is a striking work because it shatters every certainty, every attempt at rationalization, and shapes the figure of a woman poised between reality and dream, between nymphomania and frigidity, between body and spirit. Buñuel, heir and mature interpreter of Surrealism, does not merely use dream as a narrative device; he elevates it to a structuring principle, dissolving the boundaries between what is experienced and what is fantasized. The dream sequences, or those of ambiguous placement, are not mere inserts but foundational elements that reveal Séverine's repressed impulses, her masochistic search for limits, her desire for humiliation and control. Catherine Deneuve, with her hieratic and glacial beauty, perfectly embodies this duality: a porcelain shell beneath which depths of desire and anguish seethe, a figure simultaneously distant and magnetically vulnerable. Her almost sculptural impassivity becomes the perfect vehicle to explore the female psyche trapped in conventions, a bourgeois soul that finds in the forbidden the only path to an unexpected, albeit ephemeral, liberation.

Based on a 1929 novel by Joseph Kessel, it tells the story of Séverine Serizy, the bored wife of a Parisian doctor who secretly prostitutes herself in a brothel under the pseudonym Belle de Jour. But to define her actions as "prostitution" is limiting; it is rather an existential experiment, a search for extreme sensations that her comfortable but suffocating bourgeois marriage cannot offer. She is not driven by economic necessity, nor by pure lust, but rather by a profound uneasiness, an existential void that social conventions and economic affluence have carved within her. This double life is not just a narrative stratagem, but a powerful metaphor for society's schizophrenia, which preaches public morality while indulging in the most sordid private fantasies.

She thus attempts to exorcise her conscious phantoms but will fail to find meaning in life's complicated game. Indeed, her odyssey into the sordid but at the same time revealing world of the maison close leaves her perhaps more disillusioned, or at least suspended in a limbo of irresolvability. The ambiguous ending, a Buñuelian trademark, with the return of the carriage and the creeping in of doubt between reality and hallucination, is a stroke of genius that precludes any easy interpretation and condemns the viewer to confront the unfathomable. It is the triumph of traditional anti-narrative, a rejection of any consolatory catharsis in favor of a persistent disquiet.

The Italian censorship cuts caused a stir, among them a scene of young Séverine refusing to take her First Communion. This seemingly marginal episode is in reality emblematic of the conflict that grips the protagonist since childhood: an early rejection of ecclesiastical authority and its repressive doctrines, which triggers a search for freedom that later manifests in sexual deviations. Censorship, blind and myopic as is often the case, failed to grasp the artistic intent, but saw only the "profanation" of the sacred, mutilating a fundamental piece for understanding Séverine's inner turmoil.

The numerous censorship cuts disfigured the work to such an extent that, when a restored version was released, it felt like watching an entirely new film. A revelation for those who had only known the expurgated version, which confirmed Buñuel's genius in weaving a web of symbols and provocations, whose integrity was vital for the work's full resonance. The restoration of the censored scenes was not merely a matter of completeness, but a true rediscovery of the audacity and thematic coherence of a film that aimed to dismantle not only social but also cinematic conventions.

One of the many memorable scenes: Belle watches through a peephole as a Professor, a client of the brothel, is brutalized by Charlotte, a fellow prostitute of Belle, after the latter had been sent away for not being overly aggressive. This scene is a microcosm of the film: Séverine, the frigid and controlled bourgeois woman, becomes a voyeur of her own fantasy, incapable of acting directly but morbidly attracted by brutality and submission. It is the personification of her unconscious desire to push beyond her limits, to explore the masochism hidden behind her apparent composure. Charlotte's explicit violence is the distorted mirror of a need that Séverine does not yet know how, or does not want, to satisfy, but which irresistibly draws her like a moth to a forbidden flame. It is a moment of pure and almost clinical observation of perversion, where the distance between viewer and character vanishes, and we, with Séverine, find ourselves staring into the abyss.

A cursed work, it has been said, but which on the contrary proves to be of ambiguous and disconcerting depth, of a murky and morbid fascination. It is a masterpiece that continues to question the audience about the nature of sexuality, desire, conformity, and liberation, demonstrating the inevitable intertwining of the most primordial impulses and social superstructures. Belle de Jour offers no answers, but poses crucial questions, leaving the viewer in a state of perennial interrogation, a condition Buñuel loved to inflict, to stimulate thought beyond the comfortable illusion of reality. Its modernity resides precisely in this irresoluteness, in this refusal to categorize the human, celebrating its intrinsic, fascinating, and often frightening ambiguity.

Genres

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...