Brazil

1985

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

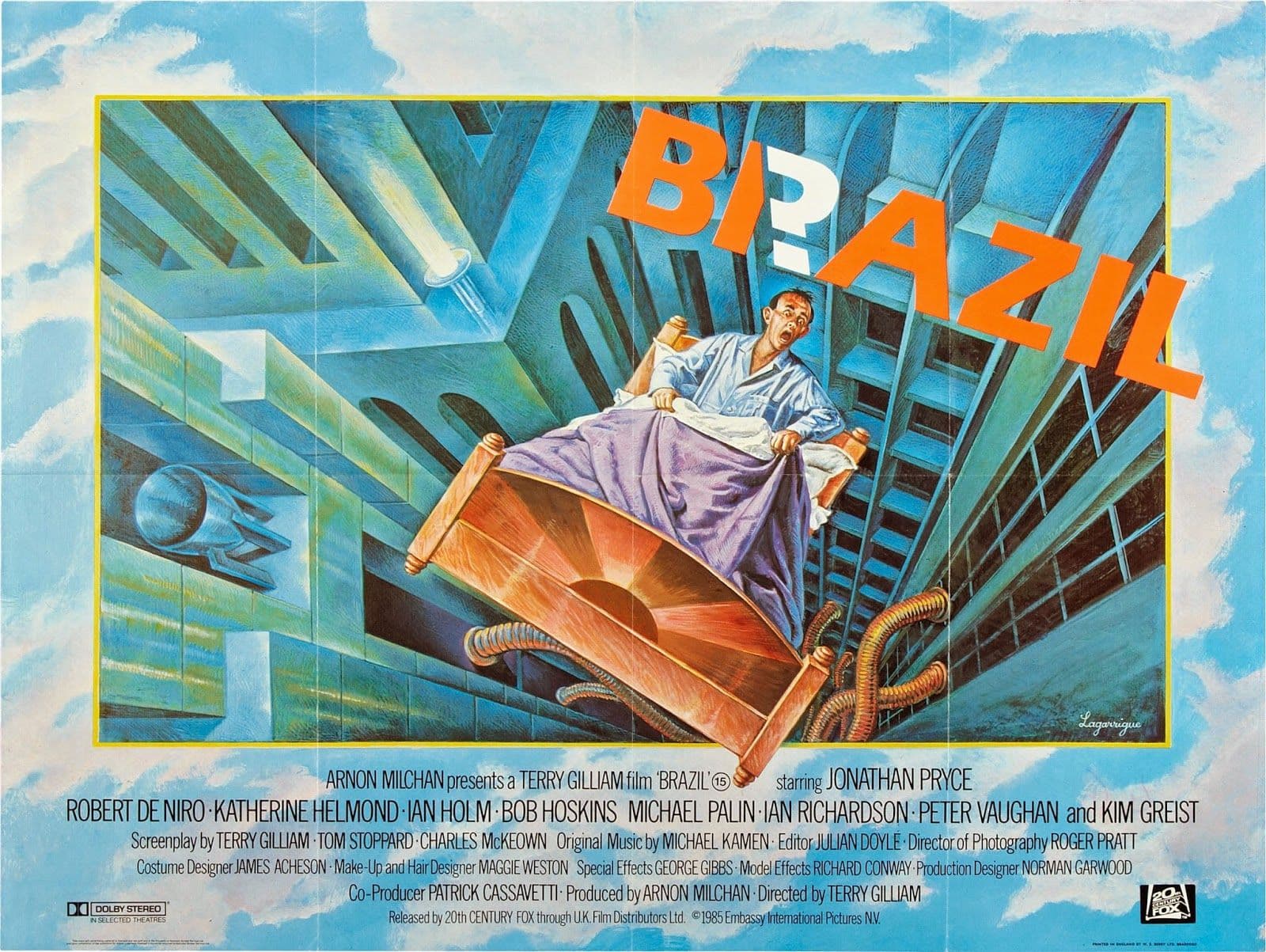

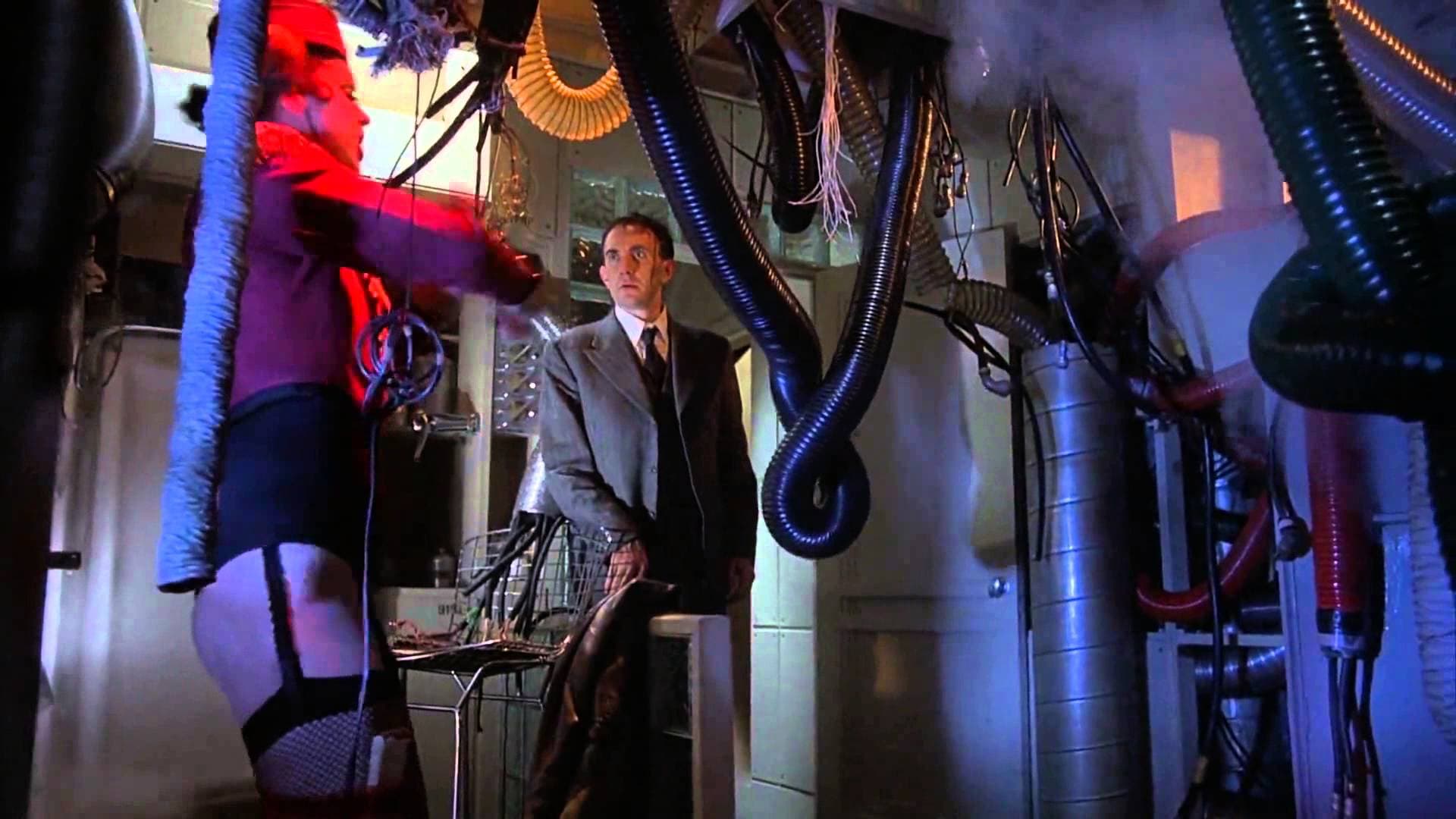

Director

Visionary work that arguably showcases Terry Gilliam at his best, at the height of his peculiar aesthetic, who directs with a dreamlike and unmistakably surreal talent a story balancing Kafkaesque claustrophobia and Orwellian dystopia. It is not merely an archetypal struggle of a humble clerk against the colossal bureaucratic system that underpins human destinies and governs lives, thoughts, and wills, but an immersion into a waking nightmare where absurdity becomes the norm, and every escape attempt clashes with the inevitable twisted logic of power. Gilliam, with his unparalleled ability as a world-builder, constructs a retro-futuristic metropolis, a labyrinth of air ducts and imposing, decaying architectures, which is itself a character – oppressive and suffocating, a grimy, hyper-technological counterpoint to the aseptic utopias of other cinematic dystopias.

Among the numerous and astute casting choices, a surprising Robert De Niro stands out, almost a spectral silhouette, barely recognizable in the role of a dissident plumber and leader of the anti-system Resistance. His appearance is a bolt from the blue, an embodiment of spontaneous rebellion manifested through manual efficiency against blind bureaucratic inefficiency, lending the film a touch of unexpected unpredictability and adding significant weight to an already stellar cast, which includes the excellent Jonathan Pryce as protagonist Sam Lowry.

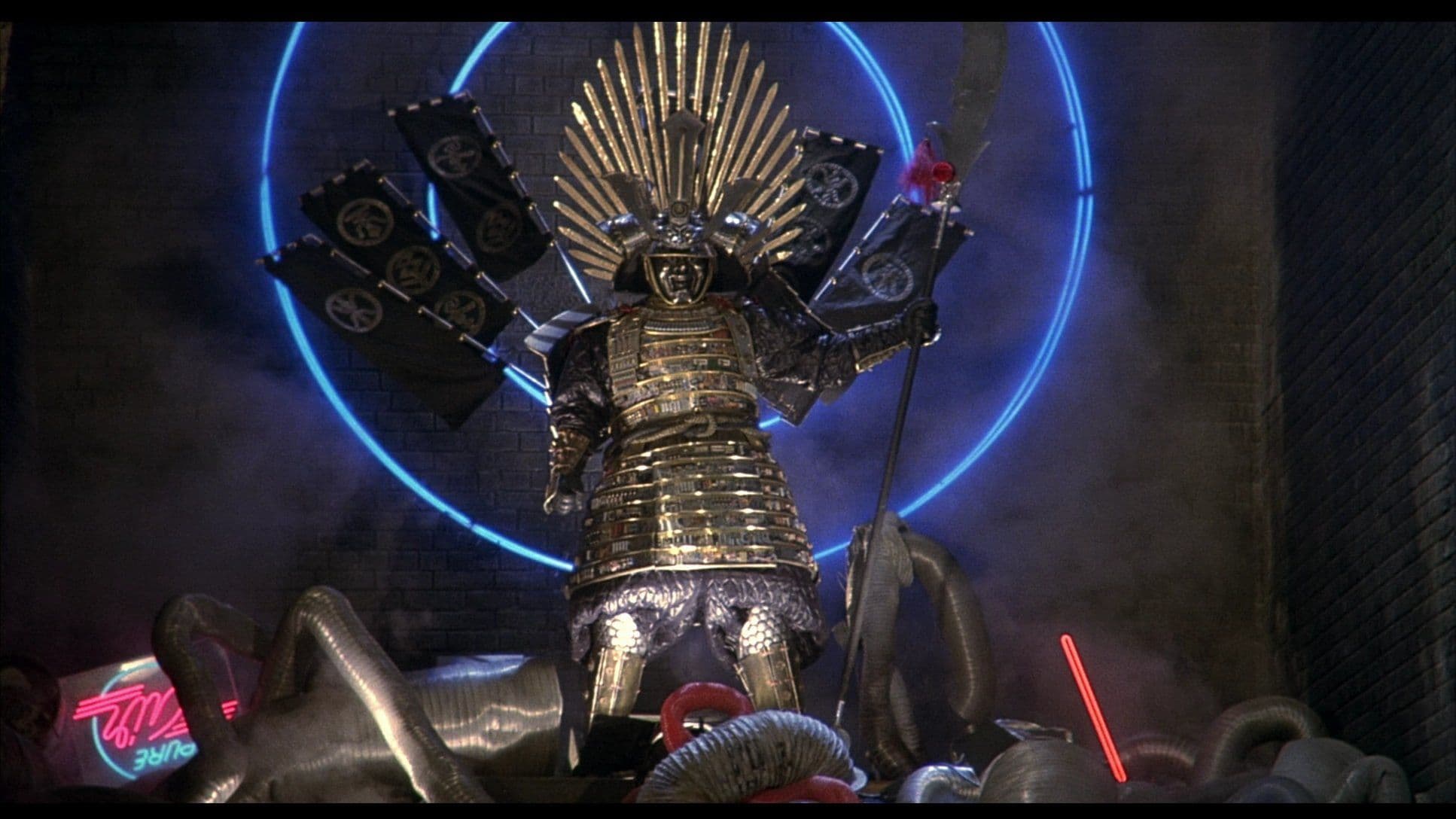

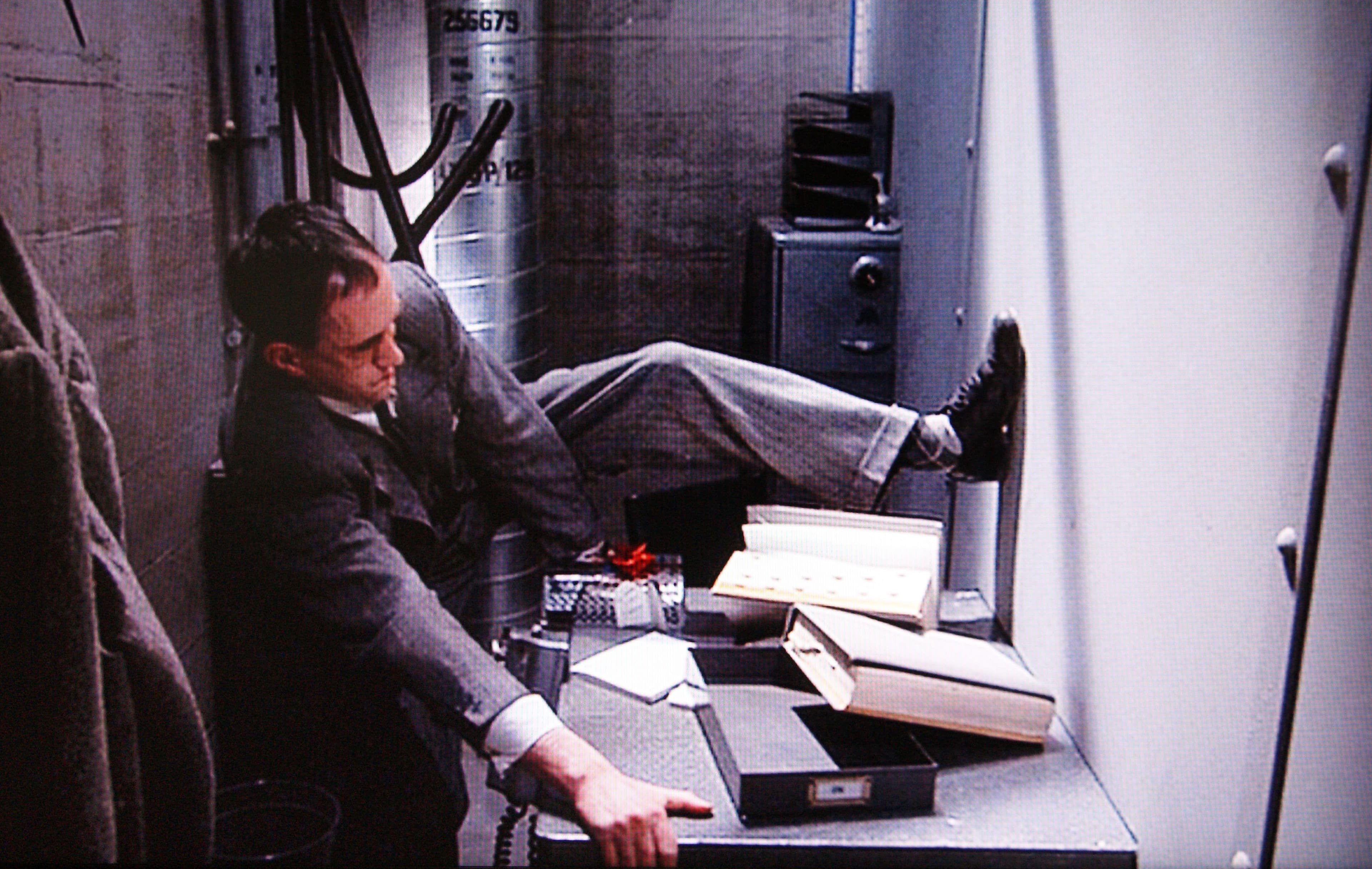

Sam Lowry is, initially, the archetype of the crushed common man, a reluctant cog in the imposing Ministry of Information, an office that evokes Foucault's panopticon due to its omnipresence, though it is strangled by its own inefficiency and redundant protocols. His only escape route lies in vivid, almost psychoanalytic dreams, in which he soars on angelic wings, a heroic and messianic figure, to reach a maiden, the personification of the freedom and love denied to him. Reality, unfortunately, is far more bitter: he is lost in the viscous coils of a sprawling institution that feeds on itself, and simultaneously pressured by a harpy-like mother, Ida, magnificently portrayed by Katherine Helmond, a slave to cosmetic surgery, a symbol of a society obsessed with appearance and the denial of transience. Sam thus finds himself a prisoner not only of an asphyxiating and oppressive System but also of social and familial conventions that stifle his every vital impulse, making him a predestined victim of a world that has lost all trace of authenticity.

The narrative fuse is ignited by a bureaucratic error of bewildering triviality: his office issues an arrest warrant for Archibanld Buttle instead of Archibald Tuttle, the elusive rebel plumber fighting against the System. A typo, an insignificant oversight in the logic of power, yet devastating for an innocent's life. While poor Buttle is apprehended by the police in a scene of terrifying brutal efficiency, almost comical in its absurdity, Sam, initially reluctantly, sets out to correct the error, driven more by personal annoyance at the irregularity than by genuine empathetic impulse, eventually coming into contact with the Resistance and, finally, with the infamous Tuttle himself. What appears to him as an opportunity for unexpected redemption, an escape from his grey and predetermined existence, instead proves to be a tortuous path that leads him through the illusions and bitter truths of an increasingly elusive freedom, culminating in an ambiguous and tragic epiphany.

Brazil is, all told, a multifaceted container brimming with memorable scenes, veritable brushstrokes of visual and satirical genius that remain etched in the viewer's memory. Emblematic is the aforementioned moment when the mother summons Sam to the cosmetic surgeon, a kind of butcher-artist, during a session of savage facial skin-lifting, almost a sacrificial ritual on the altar of vanity and eternal youth. The woman's face grotesquely deforms, pulled and distorted beyond all limits of reality, in an image that is simultaneously hilarious and horrifying, an exemplification of the body horror that pervades Gilliam's vision and his biting critique of consumeristic superficiality. And while that mask of flesh undergoes yet another aesthetic torture, Sam, in a rare moment of authenticity and despair, asks his mother not to interfere with his life, to grant him a space of autonomy. In vain, of course, because the woman, blinded by her obsession with eternal youth and social prestige, seems unwilling to listen, encapsulated in her own bubble of illusory perfection, in a dialogue of the deaf that reflects the incommunicability of the filmic world.

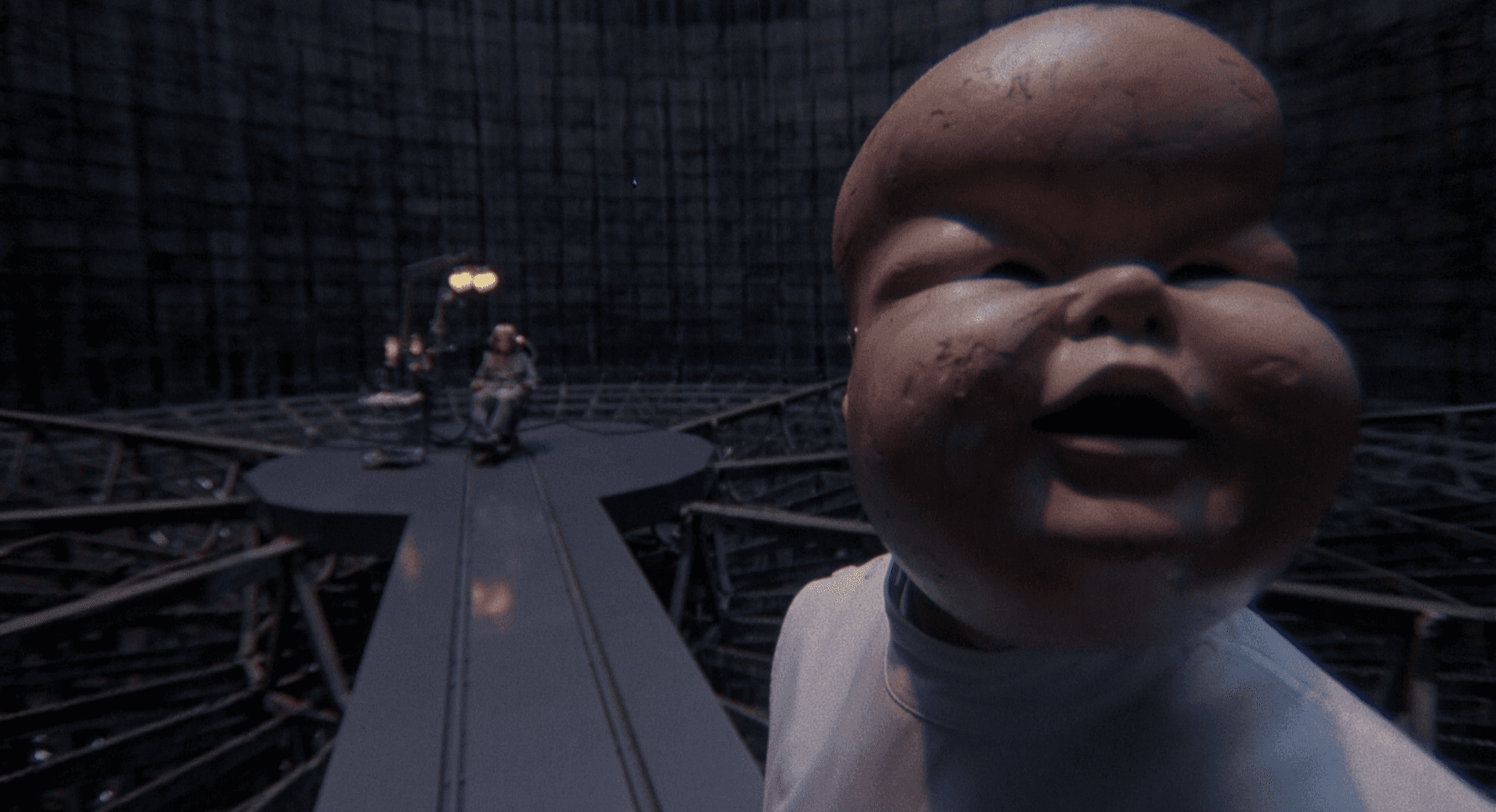

Another memorable scene, and perhaps the most iconic for its raw and bitter resolution, is the final one, where Sam is captured and placed in the center of an enormous circular hall, a Kafkaesque amphitheater illuminated by dazzling white light, awaiting torture. The almost ceremonial officialdom of the setting is chilling, transforming the act of torture into just another bureaucratic procedure. The doctor tasked with torturing him slowly approaches his station wearing a white mask that conceals his face, a symbol of the system's dehumanizing anonymity, its ability to render tormentors mere obedient functionaries, devoid of individuality or remorse. Suddenly, he turns towards the camera, revealing the features of an unsettling mask, no longer a human face but an inexpressive surface, a mirror of the moral vacuum hidden behind the most ruthless bureaucracy, while Sam awaits his fate on the horizon of the frame, almost a condemned man watching the executioner. The epilogue is a disturbing stroke of genius, a macabre ballet between hope and delirium, where reality crumbles and the only escape for Sam's mind is a flight into imagination, to the now distorted and obsessive notes of the musical theme "Brazil," which transforms from a joyful samba into a hypnotic and heart-wrenching litany, a symbol of unattainable freedom.

Brazil's narrative, far from following a linear and reassuring path, remains almost suspended, a stream of consciousness that glides between planes of existence. One gets the impression that reality could be swallowed at any moment by the dream plane, almost like a curtain of frost framing a story whose contours we cannot distinguish, and where every certainty dissolves into a vortex of nonsense and horror. This fusion of the mundane and the hallucinatory, of fierce satire and intimate tragedy, elevates the film to a rare level of psychological complexity, making it not just a dystopia, but a descent into the collective unconscious, an exploration of the fragility of the human psyche in the face of systematic repression. The visual style, a kind of comic book in images that recovers its sequential thread almost by chance, is imbued with black and grotesque humor, typical of Gilliam's genius, transforming atrocities into caricatures and drama into farce, without ever diminishing its emotional power. The film is also tragically known for its tormented production: the legendary "Battle of Brazil" between Gilliam and Sid Sheinberg's Universal, which culminated in the cutting of the director's preferred ending and the threat not to distribute the film, eerily mirrored the struggle of the individual artist against an institution, a paradox reflective of the work's very theme. Only thanks to Gilliam's tenacity and the intervention of Los Angeles critics was the full version finally released, guaranteeing its immortality and consecration. And precisely for its fairytale-like indecipherability, for its audacity in offering not easy answers but only profound questions, and for its unparalleled vision of bureaucratic madness that still resonates with dramatic topicality today, "Brazil" remains one of the most fascinating, complex, and disturbing works of all time, a timeless masterpiece that continues to challenge our perceptions of reality and freedom, leaving an indelible legacy in the global cinematic landscape.

Genres

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...