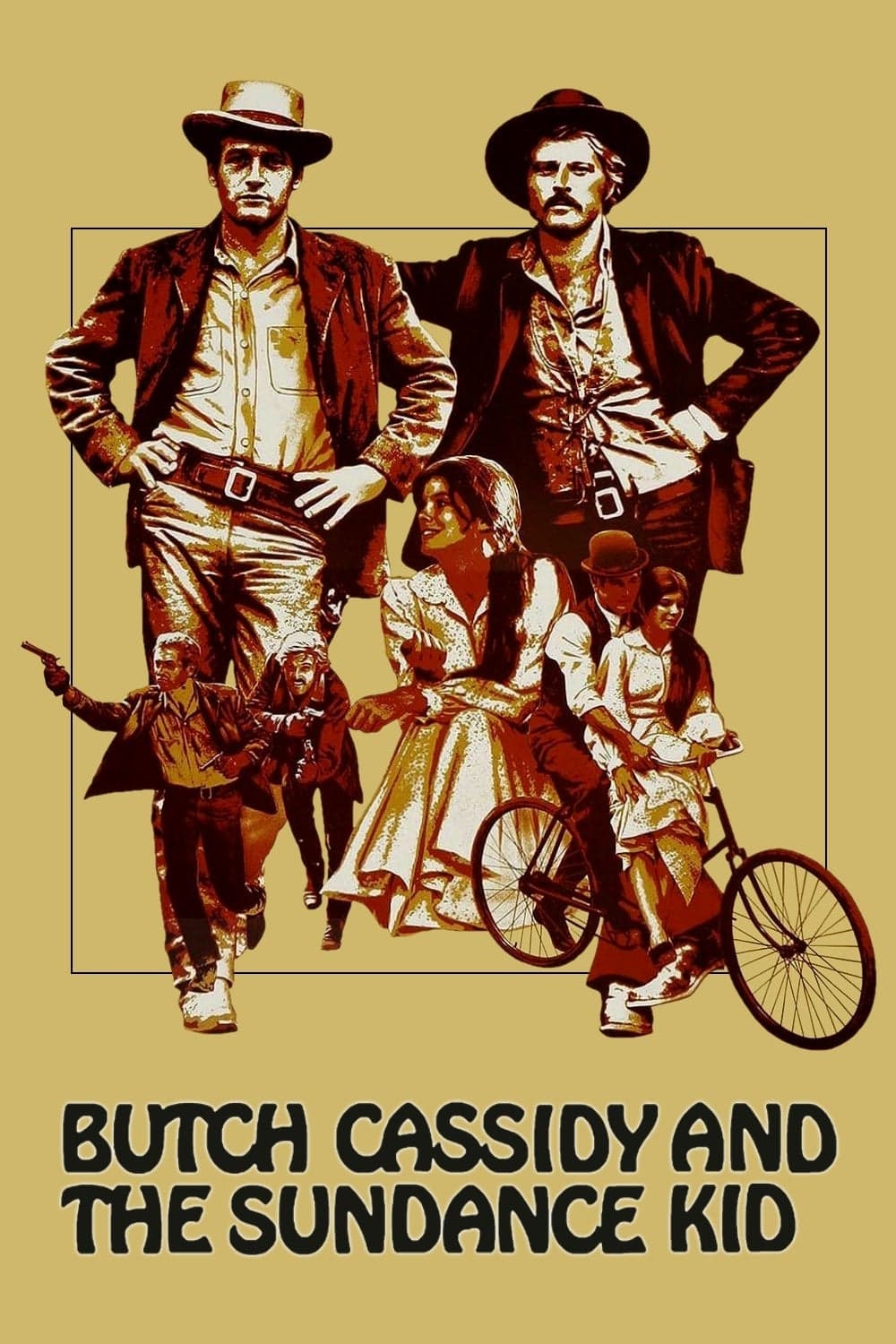

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

1969

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

George Roy Hill, undisputed master of a certain cinema of antagonism and marginality compared to Hollywood's, at times rigid and complacent, canons, signs with Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid a work that is ironic and, in some ways, tinged with a sometimes surreal comedy, establishing itself as one of the pillars of New Hollywood. In an era of profound genre and convention revision, Hill does not merely deconstruct the western, but reinvents its grammar with surprising lightness and intrinsic melancholy. The film is not a simple escape, but a bittersweet meditation on the end of an era, a lament for the wild frontier disappearing under the blows of modernity.

It narrates the story of two famous, real-life bandits, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, here transformed into almost mythical yet profoundly human figures. The writer William Goldman, Oscar-winning screenwriter for this masterpiece, performs a brilliant operation, elevating the chronicle of events into a personal epic, steeped in wit and romantic fatalism. The two are archetypes and, at the same time, deeply multifaceted and complementary characters: the first, Butch, is the charismatic mind, the mastermind of every robbery, endowed with an innate leadership ability and a contagious verve; the second, Sundance, is the armed, silent, and lethal enforcer, with his infallible Colt and a shooting skill that borders on legend. But beyond their criminal complementarity, what emerges is an almost symbiotic bond of brotherhood, one that transcends friendship and forms the true emotional core of the narrative. Their relationship, made up of affectionate squabbles, unwavering loyalty, and an understanding that even expresses itself in silences, is the unshakeable engine that elevates Butch Cassidy from a simple western to a precursor of the "buddy movie" genre.

The pair will sow terror among the ranks of the Union Pacific, the American railroad company which, with its network of tracks and its capital, embodies inevitable progress, tasked with modernizing a country still wild and lacking major communication routes. In this confrontation, the true antagonist is not a single sheriff or a well-defined rival, but civilization itself advancing, impetuous and unstoppable. Things will change drastically when an exasperated executive of the robbed Company, determined to enforce order, assembles an implacable team, made up of the best lawmen and most skilled trackers, who will hunt the two relentlessly. This manhunt, which extends for miles and days, becomes almost an allegory of the uneven struggle between the rebellious individual and the organized force of the system, between the poetic anarchy of the outlaw and the iron logic of law and industrial progress. Their pursuers, often reduced to almost abstract, unstoppable figures, represent the very destiny that hounds them, the end of an era when solitary heroes could still reign supreme.

To escape this grip, the two emigrate to Bolivia, convinced they can find a new Eden where their criminal "skills" can still be profitable. Here they will try to reinvent themselves as bank robbers, but they will find themselves in perpetual difficulty with local customs, the language, and a socio-cultural context that, paradoxically, makes them even more "fish out of water." This forced exile, which sees them move from the prairies of Wyoming to the Andean landscapes, further underscores their status as living anachronisms, men with no longer a place in a changing world, unable to adapt and condemned, ultimately, to remain true to themselves until the end.

The film is a long, passionate exercise in talent, a true virtuoso duet by Robert Redford and Paul Newman, who truly complement each other, giving life to one of the most successful and iconic cinematic duos of all time. Their on-screen chemistry is palpable, a rare chemistry that transcends simple acting and is nurtured by a deep friendship off-set. Newman, with his mature magnetism and sly irony, and Redford, with his melancholic beauty and aura of a good boy turned outlaw, do not merely portray Butch and Sundance, but are Butch and Sundance, imbuing the characters with an irresistible vulnerability and charm. Their performance elevates the film far beyond the western genre, making it a universal portrait of friendship, loyalty, and the poignant acceptance of one's destiny. It is no coincidence that, after this success, the two would collaborate again with Hill in The Sting, further cementing their status as a legendary duo and influencing generations of films centered on partner dynamics.

Hill's direction is splendid and graceful, making use of Conrad Hall's unforgettable cinematography, capable of alternating evocative sepia tones – which recall old photographs of the era, emphasizing the historical aspect of the narrative and its nature as a "memory" – with vibrant colors that highlight the vastness of the landscape and the vividness of the characters. His touch finds a witty remark in every dialogue, an ironic turn that makes the film highly atypical in the western landscape and yet, precisely thanks to this uniqueness, undoubtedly enjoyable. The innovative use of slow motion, the final freeze frame, and the unexpected inclusion of Burt Bacharach's pop music, with the celebrated "Raindrops Keep Fallin' on My Head," lend the film a sense of timelessness and playful irreverence that distinguishes it from its contemporaries and makes it a pioneering work of genre revisionism. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is not just a film about bandits, but a melancholic ode to a vanishing world, a masterpiece of balance between comedy, adventure, and tragedy, which continues to shine for its intelligence, its unshakeable charm, and the indelible mark it left on the history of cinema.

Country

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...