Cool Hand Luke

1967

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Extraordinary debut film by Stuart Rosenberg, a director with a long resume of television work, but here making his feature film debut, Cool Hand Luke (in whose Italian title the protagonist's name was inexplicably changed to Nick, perhaps to achieve better assonance, but losing the subtle Anglophone allusion to the ability to maintain control, to the proverbial "cool hand" in poker or in life) is a prison genre film shot with a wonderfully realistic approach capable of immersing the viewer in a world where a clear line of demarcation separates inmates and jailers, and where violence and abuse are the only form of relationship between men. Rosenberg's almost documentary approach, perhaps borrowed from his television experience, gives the film a tangible texture, a visual sweat that distinguishes it from previous prison dramas, such as the dreamlike Birdman of Alcatraz or the raw but more linear I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, while also anticipating the violent neorealism of future works yet maintaining its unmistakable poetic quality.

The character of Nick, played by a legendary Paul Newman (who was controversially denied the Best Actor Oscar which went to Rod Steiger for In the Heat of the Night, while George Kennedy received the Best Supporting Actor statuette for the same film) is a man who has lost everything, crushed by a society he perceives as alien and hostile, a man who, in the most complete of defeats, seeks a desperate path to redemption, or perhaps, more precisely, a desperate affirmation of his individual integrity. “There’s more enjoyment in winning when you have nothing” Nick says in one of his most famous lines, a sort of existentialist manifesto that elevates his battle from personal to universal, transforming humiliation into a springboard for the most radical of freedoms: inner freedom. Newman’s figure, already an icon of rebellion and fragile charisma, perfectly embodies Luke, endowing him with a depth that transcends the simple hero, turning him into a secular martyr, a Southern blues Christ.

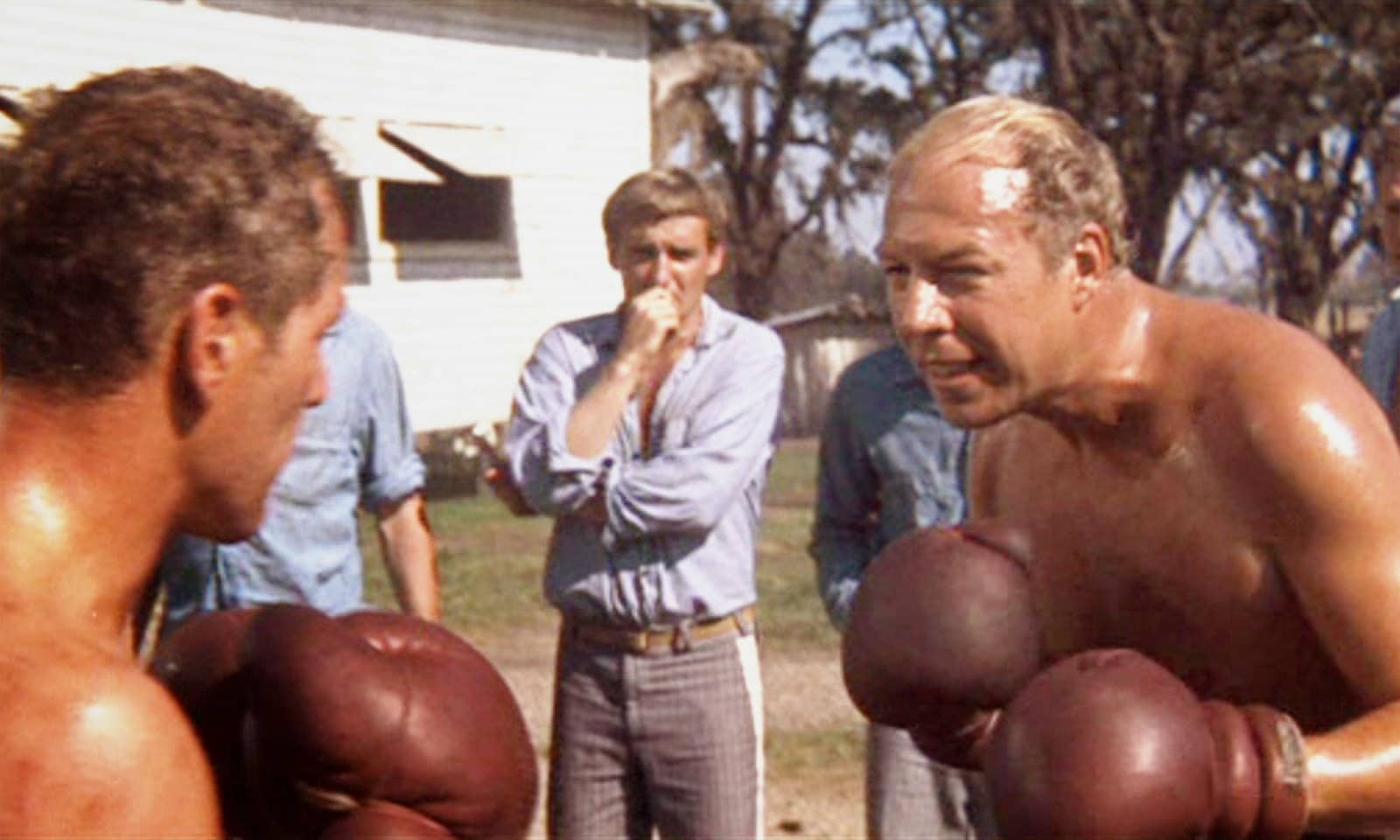

Sentenced to two years' imprisonment with hard labor for destroying, in a moment of alcohol-fueled vandalism, a series of parking meters, Nick is incarcerated in a prison camp in southern Florida, in a rural area where inmates performed labor for public works. The film, set in the deep South of the United States, uses the backdrop of chain gangs, brutal and historically real institutions, as a poignant metaphor for a repressive, almost feudal system that aims to destroy not only the body but also the spirit. Nick, devastated by losing his woman who left him for a richer man, refuses to submit to the rigid prison system and the guards' unlimited authority over prisoners. With his stubborn unwillingness to yield, he quickly becomes a symbol within the prison, earning the affection and respect of his fellow inmates. Nick establishes a deep friendship with the other inmates, especially with Dragline, the immense boxer who takes a liking to him for his pure and spontaneous ways.

During his prison life, Nick attempts to escape in every way, without calculating the short duration of his sentence. His yearning for freedom is a deeply rooted form of protest against a system that has defeated him and seeks to humiliate him. His escape attempts quickly become legendary within the prison community, and Nick's untamed, libertarian spirit gradually becomes a symbol of emancipation to cling to. His passive rebellion, that intrinsic refusal to "bend to the system," makes him a precursor to the counter-cultural ideals that were igniting America in the late 1960s, an individual who, despite his incarcerated state, embodies the purest form of independence. The famous line "What we have here is a failure to communicate," spoken by the Captain, an impassive and omnipresent figure of authority, becomes an epitaph for the incomprehension and cruelty of coercive power, a motto that resonates far beyond the prison walls, speaking of an impossible dialogue between the individual and institutions.

Many memorable scenes have made this film a timeless classic. One of the most celebrated is undoubtedly the initial boxing match between Nick and Dragline, where the two spared no tremendous blows, gaining mutual respect at the same time. That no-holds-barred encounter would indeed mark the birth of a splendid friendship between the two, a striking metaphor for how violence was the only language possible in a world where every other relationship had been severed by a repressive and authoritarian society, but also for how a raw form of communion can emerge from brutality. Equally iconic is the scene of the hard-boiled egg eating contest, an ordeal that Nick transforms into a ritual of defiance and triumph, swallowing fifty eggs and challenging the limits of body and mind, cementing his legend among his companions. And again, the grueling and repetitive road work, which Nick and the other inmates transform into an occasion for singing and camaraderie, a small act of spiritual sabotage against oppression. The film, with its stark aesthetic and Lalo Schifrin's bluesy soundtrack, is not just a prison narrative, but a parable about humanity's inescapable fate in the face of overwhelming authority, and its capacity, even in defeat, to keep the spark of dignity alive.

Cool Hand Luke is, first and foremost, a heartbreaking ode to freedom, not just physical freedom, but above all, inner and moral freedom. Emancipation from every bond and the purity of a man who, though marginalized by other men, becomes an embodiment of redemption and an indelible icon of profound humanity. His death, violent and inevitable, is not a defeat, but the definitive seal of a life spent refusing to yield, transforming his sacrifice into a warning, a desperate cry that continues to resonate, making Cool Hand Luke a timeless masterpiece, a bitter yet glorious reflection on the indomitable human spirit.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...