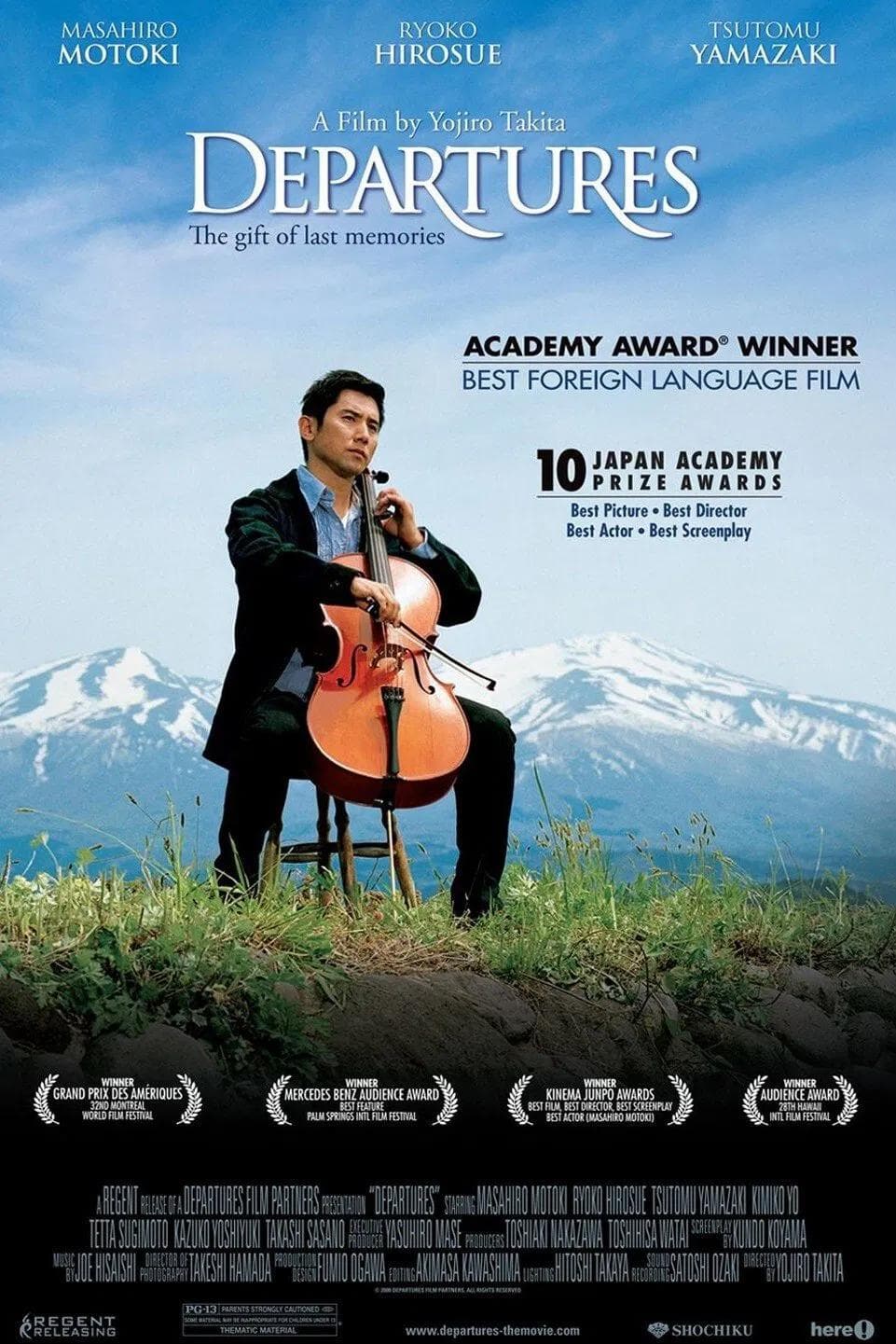

Departures

2008

Rate this movie

Average: 4.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

What does Death represent for us? How do we approach it? What sensations do we experience when we physically touch a fellow human being lying lifeless before us? These are ancient questions, as old as time if you will, yet still thorny and unresolved. The exorcism of death, its latent removal from everything that lives, has always been a more or less unconscious condition of every human social structure. In the contemporary world, moreover, the hospitalization and medicalization of death have contributed to making death an almost invisible event, a clinical and sanitized experience, stripped of the domestic and collective ritualism that once marked its passing. Every element related to death is placed in a state of semantic suspension, so that the fatal passing becomes "absence," "loss," or indeed "departure"—euphemisms that circle around the concept of Death, just as the film's title cynically plays, in a dazzling pun that will involve the protagonist, leading him to a comical misunderstanding.

Daigo is a cellist living in Tokyo who suddenly loses his job due to the economic crisis affecting his ensemble. He and his wife decide to move to his hometown to pursue a more economically sustainable life and at the same time seek new job opportunities that are unavailable to him in the big city. During his frantic search, he stumbles upon an advertisement seeking qualified personnel for assistance with unspecified "journeys." Daigo goes to the job interview, discovering that the "journeys" referred to in the advertisement are in fact "departures" (deaths). The job, in fact, concerns a role as an encoffiner, that is, one who prepares the deceased for their final journey by arranging the body to look its best. Daigo, initially dismayed, accepts the job, receiving a substantial advance, and does not reveal the nature of his new duties to his wife.

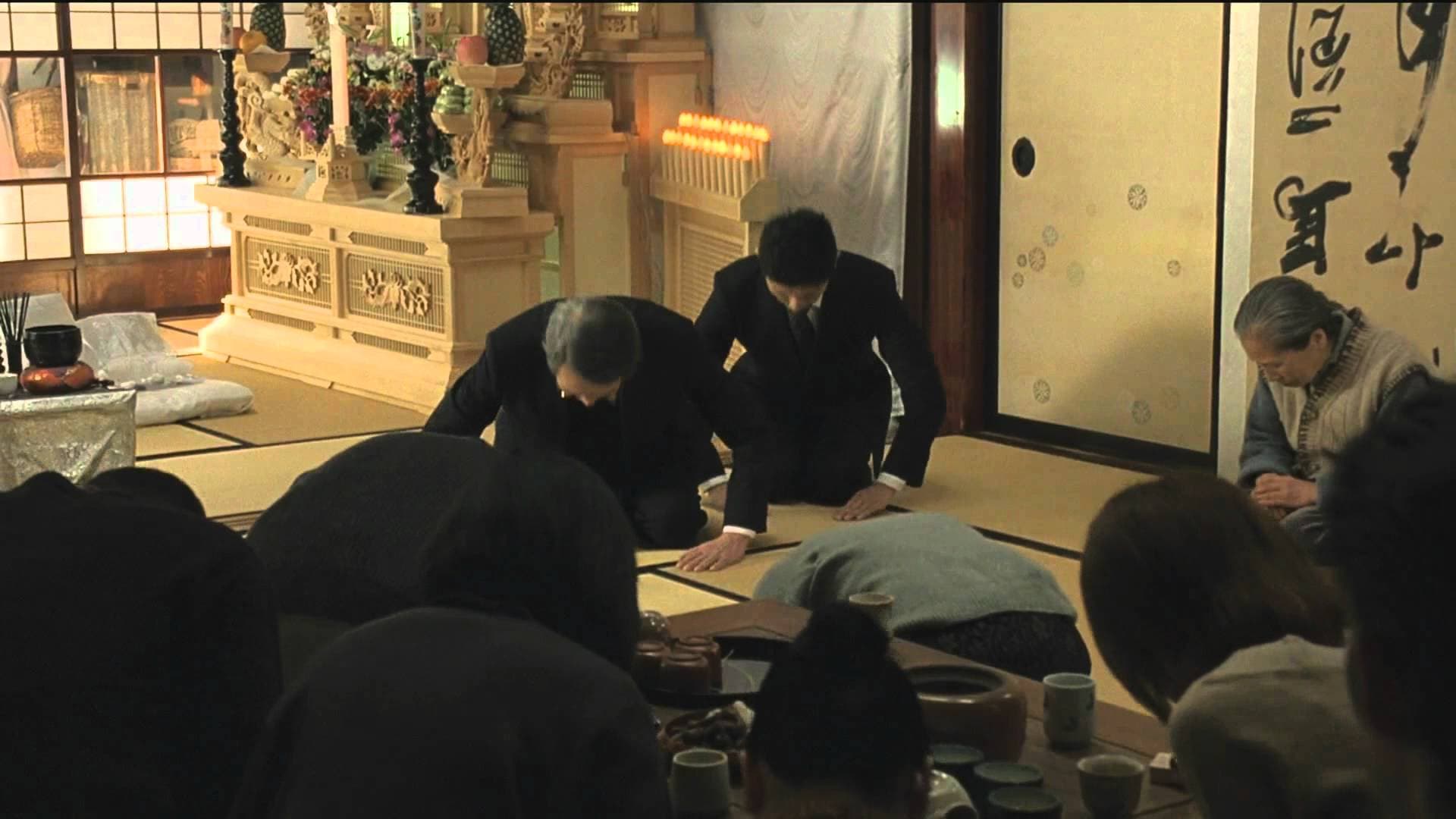

Thus begins Daigo's initiatory journey, where, thanks to the wise teachings of his boss, a man deeply in love with his work, he is introduced to the art of Nokanshi, the Japanese ritual art of caring for the deceased. This ancient profession, though fundamental, is often shrouded in a veil of superstition and social contempt in Japan, being historically associated with trades considered "impure." Takita's film challenges this perception, elevating Nokanshi to a sublime form of artistic expression and human compassion. Through this delicate liturgy, Daigo discovers the infinite love manifested in the aesthetic recomposition of a corpse. The phenomenology of all the meticulous arrangements that transform a rigid, lifeless human figure into a being who was loved and deserves to be bid farewell by their loved ones, is a true testament to civilization. It is the last great act of love towards a life torn away, a transitional ritual that not only prepares the body but also cares for the souls of the living, offering them a final opportunity to honor and accept the loss. The same precision, the same harmony required by the cello that Daigo abandoned, are found in the measured and almost danced gestures of the funeral rite, transforming the body of the deceased into a silent score. His master, a hieratic yet extraordinarily human figure, becomes for Daigo not only an instructor of techniques but a true spiritual mentor, a lay priest of an intimate and universal cult.

Thus, even those close to Daigo, who are initially disgusted upon discovering his work, come to understand the greatness of this noble and ancient Art. The initial disgust, so visceral and culturally rooted, gives way to a moving understanding, demonstrating how the honesty and dignity with which Daigo performs his task can break down centuries-old prejudices. The film thus becomes an intense meditation on overcoming social barriers and the power of compassion. Daigo, through the practice of Nokanshi, will thus be able to draw close to his father again, who, on his deathbed, will reveal to his son a precious secret preserved through the dusty oblivion of time. The revealed secret is not just an object, a stone smoothed by time that becomes a tangible bridge between generations, but the silent monologue of an entire life, the reconciliation with absence and with a love never fully expressed. A universal narrative topos that, in Takita's hands, takes on the contours of an almost mystical revelation.

Takita's film is surprising and precious. Extreme care in visually and conceptually rendering the Art of mortuary recomposition at its best makes this work unique and fascinating. Takita, with a directorial mastery that evokes the quiet observation and profound humanity of an Ozu or the tenderness of a Kore-eda, yet with a highly personal stylistic signature, transforms the macabre into the sublime. Every shot is chiseled, every light calibrated to enhance the dignity of the ritual and the depth of feelings. The measured slowness of the narrative pace, far from being a defect, allows the viewer to savor every gesture, every expression, every subtle transformation of body and soul. The classical-leaning soundtrack, curated by the legendary Joe Hisaishi, finally transforms the narrative experience into a kind of catharsis, not only accompanying the images but becoming an integral and resonant part of this melody of life and death, in total harmony with the flow of the story. International recognition, culminating with the unexpected but richly deserved Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in 2009, was a surprise to many, but testifies to the film's ability to transcend cultural barriers, speaking a universal language of acceptance, dignity, and the beauty that can be found even in the inevitability of the end.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...