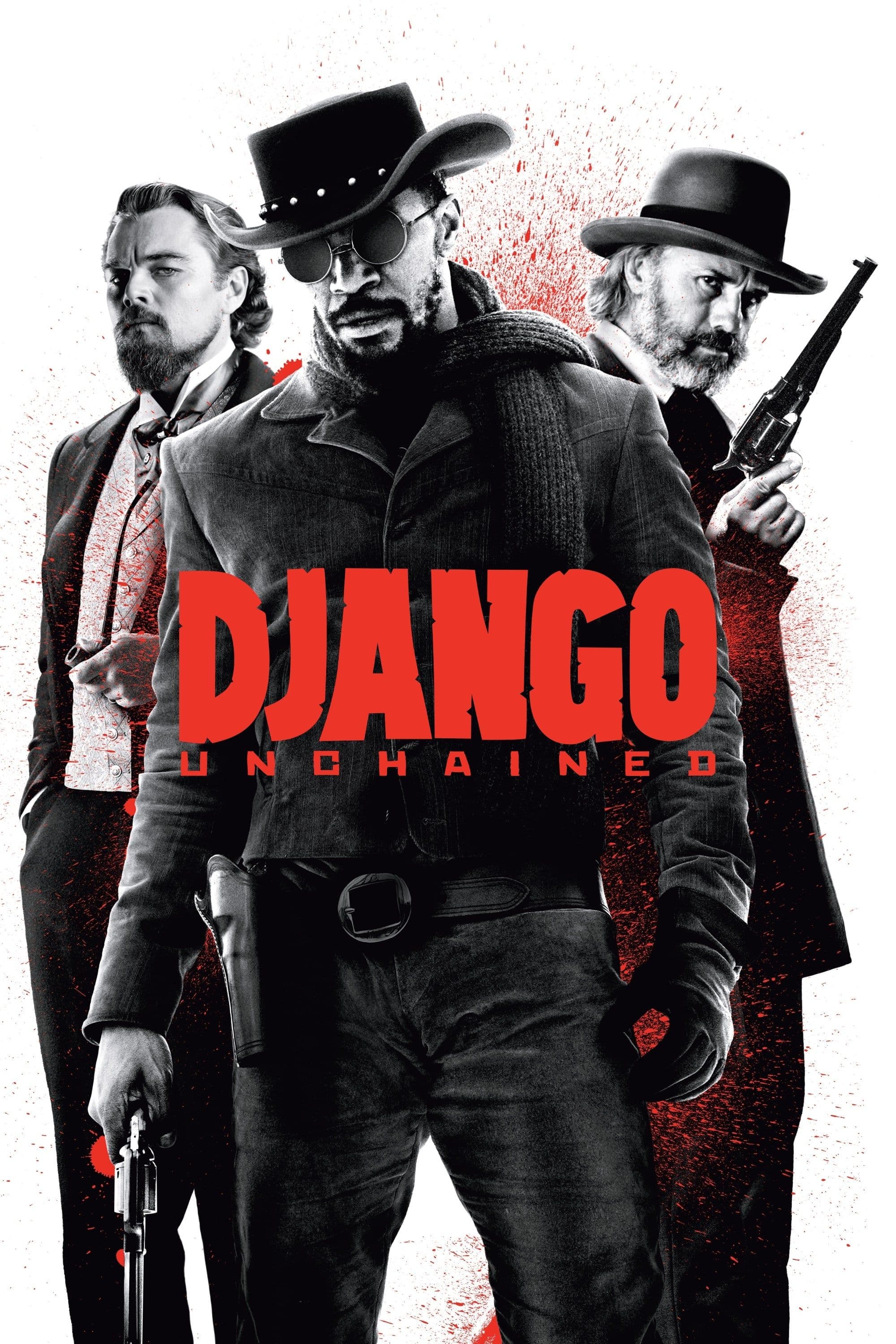

Django Unchained

2012

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Tarantino continues his journey through the cinematic contaminations that are the pillars of his artistic genesis, a true postmodern architecture built on the deconstruction and reassembly of genres and iconographies. His cinema is not mere quotationism, but a refined alchemy that transforms the familiar into something surprisingly new and subversive.

In this case, he undertakes an exceedingly risky, even daring, operation, drawing heavily from Corbucci's most murky and iconoclastic spaghetti westerns – whose original Django, played by an icy and vengeful Franco Nero, left an indelible mark on the history of genre cinema – and pulling one of the historical characters of that period and genre out of the hat: Django. The audacity lies not only in re-evoking such a sacred name, but in placing him within such a painful and controversial historical-social context as pre-Civil War slave-owning America, a territory that classic westerns often ignored or sugar-coated. It is an operation not just of homage, but of a true re-functionalization of the myth of the lone avenger, dressing him in a mission of historical and moral liberation.

Tarantino, as is his custom, diabolically intertwines the figure of the redeemed gunslinger, a genre archetype, with the liberation struggle of Black slaves in the racist American South of the late 19th century. This audacious grafting is not a mere narrative device; it is the film's beating heart, a brutal superposition between the ruthless and amoral aesthetics of the Italian Western and the raw reality of an era stained by the horror of slavery. The result is a surreally compelling story, imbued with a stylized and cathartic violence that, while not sparing the brutality of the subject matter, sublimates it through the hyperrealist filter of his unmistakable directorial eye, transforming historical drama into an epic of personal and collective revenge. The parallel with Inglourious Basterds is striking: both films are exercises in historical revisionism where justice, denied by reality, is restored with brute force and a good dose of pulp fantasy.

Dr. King Schultz, a fake dentist who is actually a German bounty hunter, a figure of disarming eccentricity and exquisite dialectic, frees the slave Django and teaches him the trade of a gunslinger. Their relationship is a magnificently orchestrated duet: on one side, Schultz's enlightened European pragmatism, on the other, Django's primordial hunger for justice. After availing himself of Django's valuable services, recognizing his worth and potential, the doctor helps him find his Broomhilda, like a new Siegfried in the Nibelungen saga. This fascinating Wagnerian allegory, delicately but persistently suggested, elevates the tale of revenge to an almost mythological dimension, imbuing Django's quest with an epic gravitas that transcends mere genre entertainment. His love for Broomhilda becomes the driving force that allows Django to overcome his physical and psychological chains, to learn to fight, and ultimately, to reclaim his dignity in a world that brutally denied it to him.

Needless to say, the film remains enjoyable from the first to the last frame, a visual and auditory triumph that captures the viewer and doesn't let go, with delightful inventions and more or less veiled homages to 1960s Italian cinema. The soundtrack, for example, is an eclectic soundscape that blends original Morricone-style tracks with unexpected hip-hop and R&B incursions, creating an estranging contrast that is by now a Tarantino trademark. Perhaps the most striking of the homages is the cameo by Franco Nero himself, the original Django, in a memorable scene that is a true generational passing of the torch, an affectionate tribute, and a seal of approval. But the influence of the Italian Western is also evident in the direction, with those extreme close-ups on the eyes, the stylized duels, and the emphasis on visceral violence that spares nothing to convey the horror of the context.

Furthermore, the work, beyond the director's flair, is ennobled by a titanic Christoph Waltz. His portrayal of Schultz is not only superb, but a tour de force of charisma, sharp intellect, and a lethal, courteous brutality that effectively overshadows the other protagonists, reducing them almost to mere supporting characters. Waltz, here in his second Tarantino triumph after Colonel Hans Landa in Inglourious Basterds, once again demonstrates a unique mastery of language, an ability to make words dance like sharp blades, making every dialogue a small theatrical masterpiece. His figure as an "enlightened" bounty hunter, with his moral principles sometimes ambiguous but always rigorous, serves as a narrative and moral lynchpin for much of the film, pushing Django not only to shoot, but to think and to emancipate himself. Jamie Foxx, in the lead role, also delivers a performance of considerable depth, evolving from a silent and brutalized slave to an icon of relentless vengeance, but the power of Waltz's stage presence is unparalleled.

Dozens of memorable scenes, true jewels embedded in the plot. From the understated killing of the fake sheriff Bill Sharp, which with its lightning efficiency reveals Schultz's true nature, along with an equally understated and disarming public explanation of how the sheriff was actually a cattle rustler in disguise – all delivered with delightful pomposity and ironic verve, in front of a hundred barrels pointed at him, in a crescendo of tension and surreal comedy. Or the pivotal scene, the point of no return, when the ruthless and refined slave owner Calvin Candie (a magnificently repellent Leonardo DiCaprio, whose character embodies the banality of evil disguised as Southern elegance) realizes the true nature of Schultz's and Django's visit to his mansion, Candyland (a name that evokes hell in disguise), and stages a dramatic confrontation in the dining room, amidst finest porcelain and silver cutlery. This sequence is a pinnacle of writing and acting, an intellectual duel that degenerates into a bloodbath, highlighting how apparent civilization can conceal the most ferocious barbarity. And one cannot fail to mention the figure of Stephen, portrayed by an unsettling and unforgettable Samuel L. Jackson, a chilling symbol of internalized oppression and complicity in evil.

As in every Tarantino film, the ocean of citations, homages, and cinephile appropriations is so vast that its boundaries are imperceptible, making the viewing a layered experience that satisfies both the cinema enthusiast and the neophyte. Every shot, every line, is imbued with an immoderate love for the seventh art, a mosaic of references that is not limited to the western genre but draws heavily from blaxploitation, kung-fu, and the most disparate art-house cinema, without ever falling into mere stylistic exercise. Tarantino doesn't quote, he reinvents. And to quote Leopardi, regarding such a profound and stimulating sea: "To shipwreck is sweet for me in this sea"... a shipwreck that is, in reality, the sweetest of discoveries.

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...