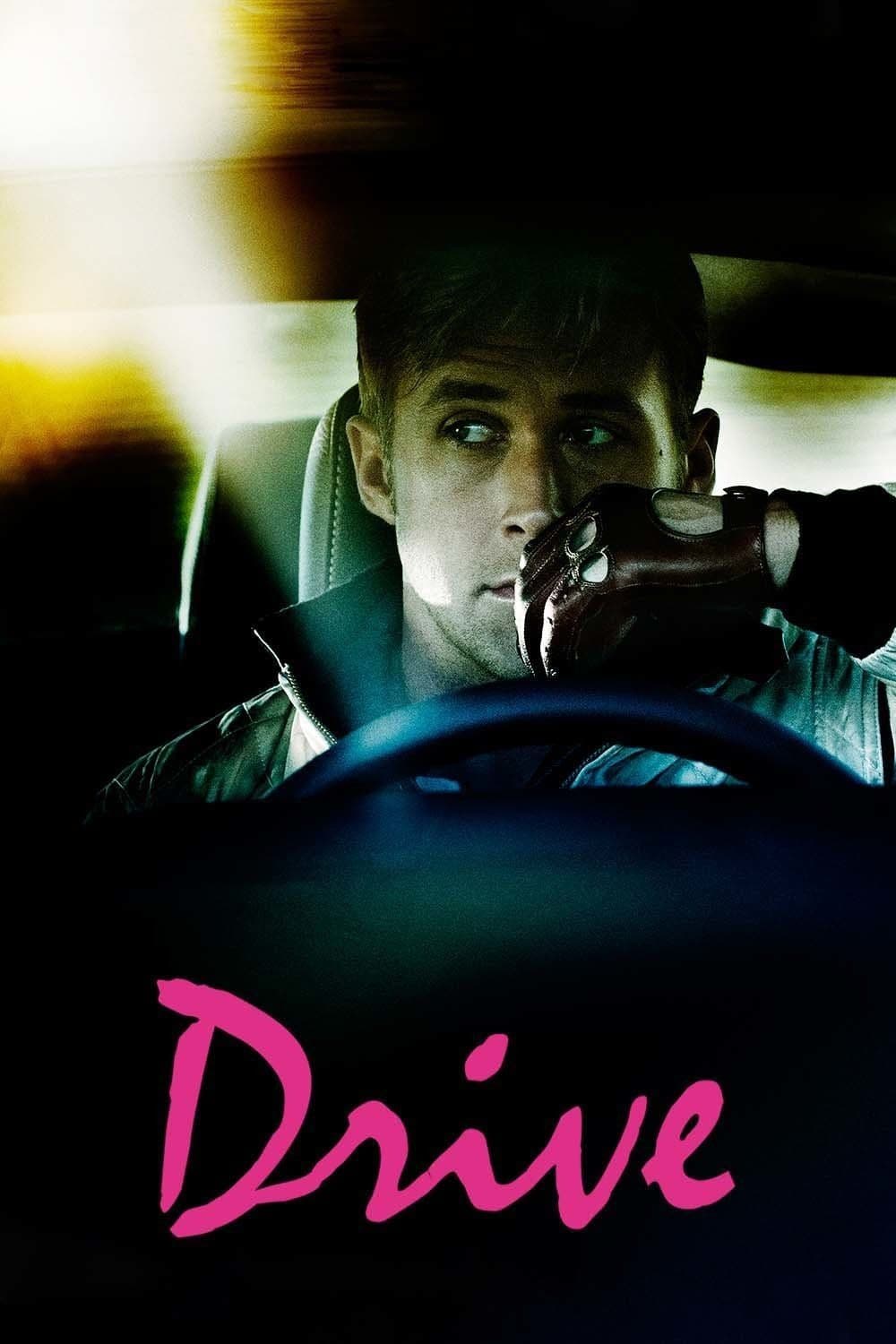

Drive

2011

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Drive is perhaps noir's last flourish before ending a run that spanned over seventy years. Or perhaps, more accurately, it is one of its most vivid and unsettling rebirths, a deep dive into its murky waters but with a neon color palette and a pulsating rhythm that set it apart from the past. Noir, after all, never truly died; it simply adapted, morphing into neo-noir, acquiring new forms and sensibilities, but maintaining its fatalistic and disillusioned essence intact.

But does it make sense to speak of the noir genre in our times, and particularly for this excellent work by Nicolas Winding Refn? We are convinced it does. The resonance of classic noir themes, such as moral corruption, inescapable vengeance, and the futility of heroism in a cynical world, has never been more relevant. In an era of uncertainty and exacerbated individualism, noir's appeal, with its exploration of the grey areas of the human soul and collapsing social structures, finds fertile ground. Refn does not merely pay homage; he deconstructs and recomposes the genre, imbuing it with a new, unsettling vitality.

Let's analyze the factors that comprise a classic noir story from the 1950s (the decade of its greatest splendor): the protagonists are often lost in their wavering morality—drunks, robbers, prostitutes, murderers, failures, thugs, people who have been marginalized by society and harbor a bitterness mixed with cynicism and disillusionment towards it, lending the story a bitter taste of stagnant defeat. Emblematic figures like those drawn from the pages of Raymond Chandler or Dashiell Hammett, private investigators and anti-heroes forged by harsh post-war reality, populated a universe where law was a malleable concept and justice an illusion. Theirs was an existential nihilism, the awareness of being pawns in a much larger and often meaningless game.

The protagonist of Drive has no name; he works as a stuntman when needed, a mechanic, and earns extra money by driving for robbers. This absence of a name, this almost archetypal depersonalization, elevates him to a symbol, a modern Golem or a silent Paladin, devoid of a defined past, yet possessing a moral rigidity—or at least a code of honor—that clashes with his surroundings. His is an ascetic life of complete solitude, an almost monastic discipline that makes him a detached observer of the chaos around him, until it is utterly disrupted by the woman he falls in love with, Irene, and her son. This intrusion of innocence and vulnerability into his solitary universe is the spark that ignites the drama, transforming the Driver from a mere cog in a criminal mechanism into an unstoppable force driven by protection and revenge.

But everything ultimately spirals into an endless vortex of violence where brutality and inhumanity erase any hope of redemption. The violence in "Drive" is never gratuitous, despite its often unexpected and shocking brutality. It is the logical and inevitable consequence of noir's premises: a world where attempts at salvation are consistently stifled by an immutably corrupt reality. The Driver, in his glacial calm, transforms into an almost mythological figure of a revenger, a solitary vigilante who acts outside of any law, with a coldness that reflects his inner isolation. The elevator sequence, a masterpiece of tension and sudden, jarring violence, crystallizes this transition, revealing the protagonist's predatory and implacable side. It is the failure of the romantic fairy tale, the inevitable dissolution of any illusion of normalcy in the face of human bestiality.

Another salient element of noir is chiaroscuro; the films were indeed immersed in an almost constant penumbra, and light was rarefied, bathing the visual field in a milky, gloomy black and white. Even in Drive, although Refn chose color, the use of light is masterfully shadowy; plays of shadows dance on the protagonists' faces, and most sequences are shot at night. But here, color is not a mere aesthetic whim; it is a language. The neon lights of Los Angeles, the subdued lights of bars, the deep blue of Californian nights, and the bright pink of the Driver's scorpion jacket not only paint an atmosphere but also underscore moods, omens, and symbolisms, evoking pulp aesthetics and 1980s video game imagery while maintaining the existential gloom of classic noir. Newton Thomas Sigel's cinematography is an exercise in style, where light and shadow do not merely shape spaces but also define the moral boundaries of the characters.

Another fundamental element of noir cinema is money, around which the narrative always revolves: in Drive, the keystone of the story (taken from James Sallis's novel of the same name) is a heist loot that the Driver (who has no name, nor ever will in the film) agrees to acquire to protect the woman he loves. This money is never seen as a way out or a promise of happiness, but rather as the catalyst for further downfall, a magnet for violence and destruction. It is the classic noir "macguffin," the object of desire that unleashes a vortex of uncontrollable events, revealing the predatory and ruthless nature of the criminal world hidden beneath the glossy surface of the "City of Angels." Love, here, is not redemption, but the most dangerous of capital sins, because it renders the solitary protagonist vulnerable, dragging him into a conflict that is not his own, but from which he cannot escape.

A barrage of ruthless retaliations and brutal vengeances leads the viewer through a sordid, lightless world, a long, asphyxiating tunnel without any prospect of escape. Los Angeles, in "Drive," is not the postcard city, but an urban labyrinth of dark alleys and decaying motels, an indifferent metropolis that devours its inhabitants, a silent and menacing character that reflects the inner desolation of the protagonists. It is a world without salvation where the director sagaciously moves his camera like a silent voyeur studying the behavior of tiny insects struggling in vain within an immense spiderweb. This spiderweb metaphor is potent: it suggests the inescapability of fate, the feeling of entrapment that pervades every frame. The soundtrack, a hypnotic mix of synthwave and melodic tracks oscillating between melancholic nostalgia and impending menace, acts as the pulsating heart of this spiderweb, punctuating the slow and inexorable rhythm of the downfall. The minimalism of the dialogues enhances this sensation, allowing images, sounds, and silences to tell the story, immersing the viewer in an almost meditative contemplation of violence and pain.

The result is a brutal and fascinating work, raw and powerful, with a language that tears through the darkness to define a new, precious chapter in noir cinema. "Drive" is not just a homage to a genre, but a radical reinvention of it, an ode to '80s aesthetics filtered through a lens of contemporary fatalism. It is a film that gets under the skin, leaving a lasting impression thanks to its recognizable aesthetic, its sparse yet meaningful narrative, and Ryan Gosling's iconic and silent performance. It is proof that noir, in all its nuances, continues to be an unsettling mirror of our deepest fears and most fallacious aspirations, reasserting its eternal relevance in the cinematic landscape.

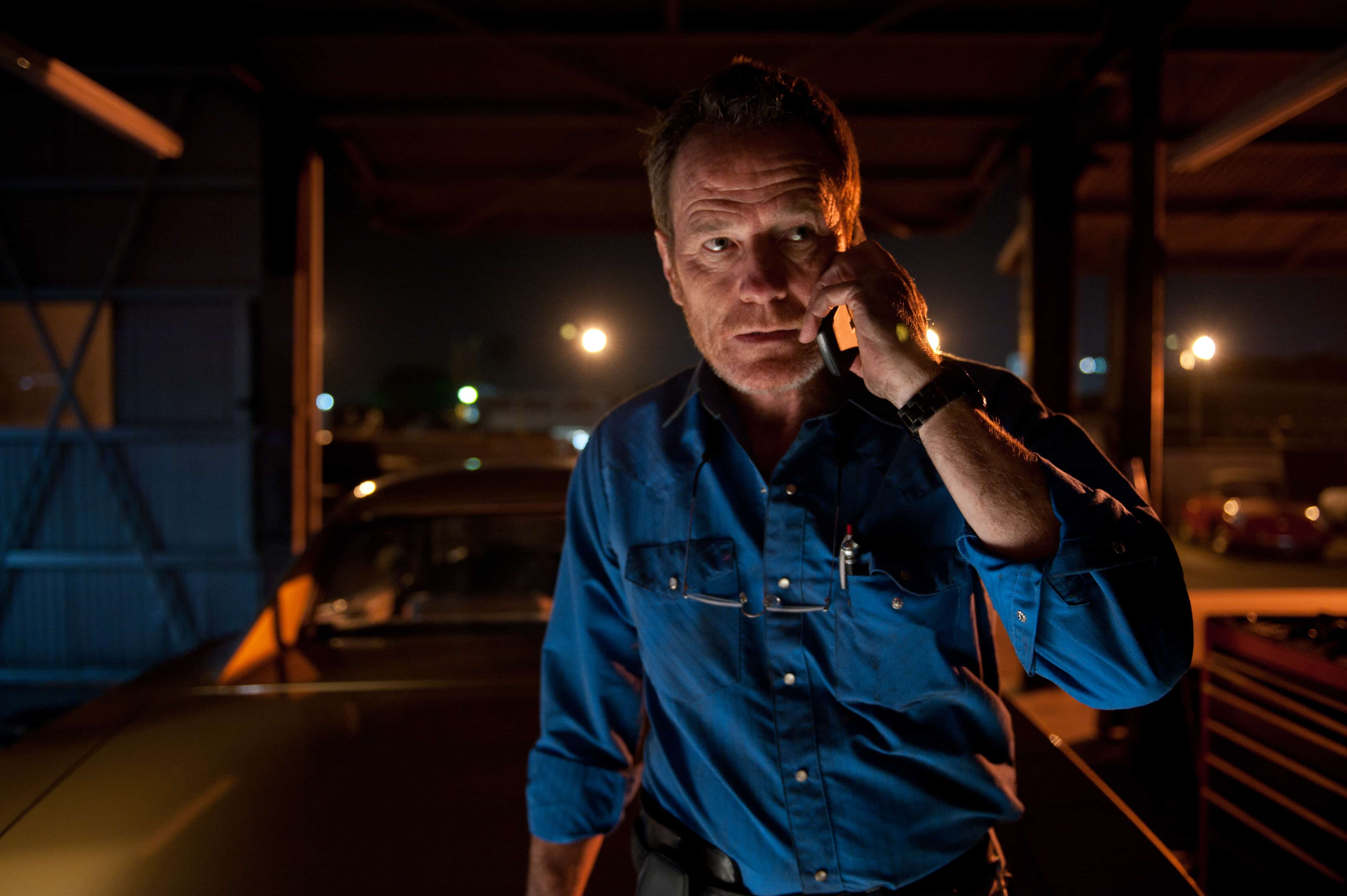

Main Actors

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...