Earth

1930

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A great naturalistic poem celebrating the relationship between the Soviet citizen and their element. All presented in a sublime aesthetic form, underpinned by a lyricism that is never mannered. A lyricism that does not confine itself to mere aesthetics but becomes a vehicle for an almost tactile experience, a sensibility that envelops the viewer in the physicality of the earth and its cycles. While Eisenstein used montage to stimulate the intellect and Vertov to document the raw reality of the "cine-eye," Dovzhenko employs it to evoke an emotional and almost ancestral resonance, forging a pantheistic ode to life itself. Dovzhenko signs one of the greatest masterpieces of silent cinema with a vision permeated by an extraordinary sense of imagery.

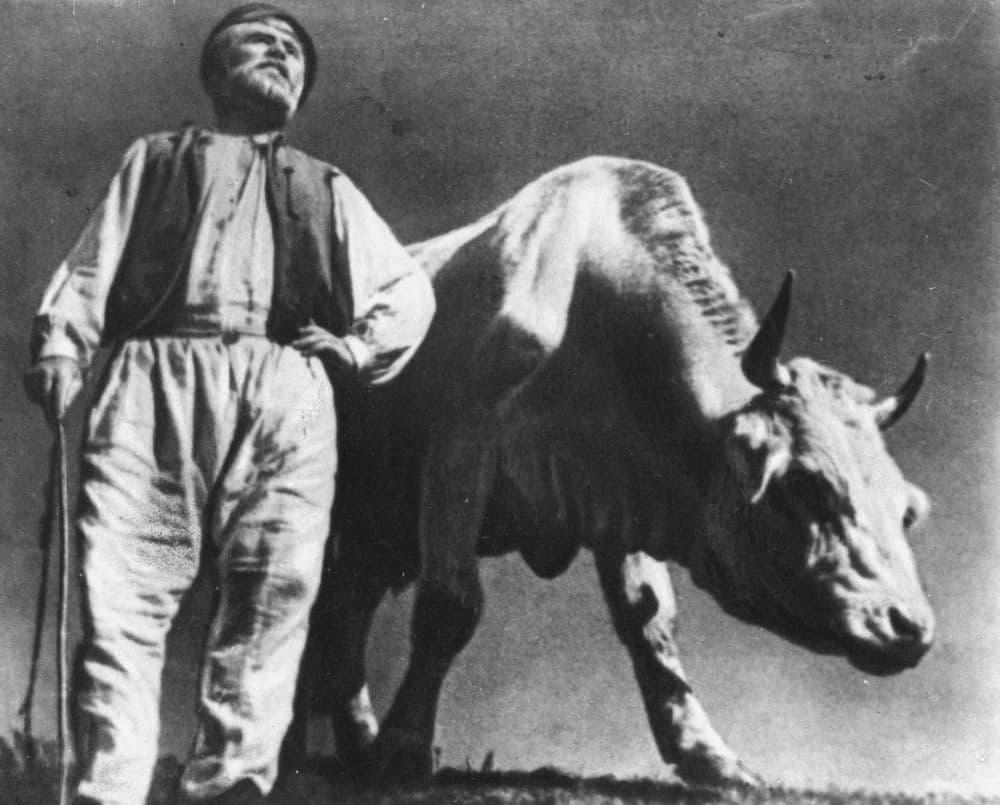

Earth represents a monumental work in the history of cinema, a visual poem that celebrates nature, peasant life, and the communist ideal. Dovzhenko, with his poetic sensibility and visionary gaze, transcends the canons of socialist realism, as Eisenstein did before him, to create a film of extraordinary beauty and expressive power, in which the earth, understood both as a natural element and as a homeland, becomes the absolute protagonist. This telluric centrality manifests in every frame, from the rustling of wheat in the wind to the fresh furrows of the field, elevating matter to an almost divine entity—a boldness that, within the context of Soviet didacticism, was not exempt from heavy criticism for its alleged "bourgeois naturalism" and "mysticism," deemed incapable of conveying the revolutionary message with due class clarity. The work, set against the historical backdrop of forced collectivization in the Soviet Union, stands out for its originality and symbolic strength, offering a lyrical and profoundly human interpretation of the relationship between humanity and nature.

The film also reveals influences from Soviet avant-garde cinema, particularly Eisenstein's intellectual montage and Vertov's "cine-eye." Dovzhenko uses montage creatively, alternating close-ups, long shots, and detailed frames, creating a dynamic and engaging visual rhythm. His art is not limited to a formal exercise; it translates into images the depth of a Ukrainian soul steeped in its connection to the land, transcending propaganda dictates to touch universal chords, almost as if to infuse the viewer with the same lifeblood flowing through the fields.

In a Ukrainian village, at the height of a hot summer, old Semën Trubenko dies peacefully under an apple tree, surrounded by his family. His passing, in harmony with nature, is a prologue of serene acceptance of life's cycles, contrasting with the violence that will soon erupt. His son, Vasil, a young and passionate communist, leads the movement for land collectivization and the introduction of the first tractor into the village, clashing with the resistance of the kulaks, the wealthier peasants. The tractor, a symbol of progress and forced mechanization, is not merely a tool here, but almost a metallic golem breaking into a primordial order, unleashing a palpable tension between the archaic and the modern, between tradition and ideological imperative. This collision is the heart of the conflict, not only between rich and poor peasants, but between two radically opposed worldviews: one rooted in natural cyclicality, the other in the historical acceleration imposed by ideology. One night, as he returns home euphoric after plowing the fields with the new tractor, Vasil is killed by a kulak. His death, tragic yet epiphanic, plunges the village into despair, but his funeral transforms into a celebration of life and the earth's fertility. The long-awaited rain falls on the fields, while a young pregnant woman symbolizes the continuity of life and the community's radiant future. The final scene, with the purifying rain blessing the earth and the figure of the pregnant woman emerging as an icon of perpetuation, transcends mere political representation to take on the nuances of a pagan rebirth ritual, a hymn to fertility that defies death and violence, and which, due to its almost mystical power and the depiction of Vasil's nudity, raised considerable perplexity among the guardians of Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy, who accused Dovzhenko of indulging in an aesthetic not conforming to the precepts of socialist realism.

The camera, with fluid movements and evocative shots, captures the beauty of the wheat fields, the majesty of ancient trees, and the power of natural elements. Vasil's death, as a young and idealistic supporter of collectivization, becomes a pretext for a reflection on life and death, on nature's eternal cycle, and on the continuity of life. Vasil's funeral, transformed into a celebration of life and community, is one of the film's most memorable scenes: images of peasants dancing and singing, the funeral procession winding through the wheat fields, and the fusion of man and nature create an atmosphere of intense emotion and solemn beauty. It is a collective ecstasy, a funeral elegy that transforms into a Dionysian dance, where grief is absorbed and overcome by the uninterrupted promise of life. This ability to infuse the sacred into the mundane, the cosmic into the contingent, distinguishes Dovzhenko from his contemporaries, projecting "Earth" beyond the confines of its time and its programmatic intent. An incredibly modern work, characterized by an exquisitely refined aesthetic taste and a talented use of the camera. The film, though created in a specific historical and political context, retains its relevance, inviting the viewer to reflect on the relationship between humanity and the environment, on the importance of community, and on the power of hope. A film that still moves and captivates today, an unequivocal sign of an art that resists time by overcoming its power of decay. A lesson in cinema, but above all a lesson on existence, on the fragile yet indissoluble pact between humanity and the soil that nourishes and embraces it, a work that, even today, resonates with the force of an archetype, calling us back to our deepest roots and to resilience in the face of historical becoming, a cinematic "Genesis" that continues to sprout in the collective subconscious.

Main Actors

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...