Easy Rider

1969

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Freedom.

To run away, to travel, to break free from society, to tread new paths, to be different, non-conformist. A freedom that, in "Easy Rider," manifests not only as a beat utopia but also as an inevitable condemnation in an America heading towards an era of deep divisions and disillusionment. Dennis Hopper's film, presented to the public in the fateful 1969, is not just a snapshot of a tumultuous decade, but a prescient epitaph for the idealism of the counterculture, a requiem for the hope of a "New Frontier" that would never see the light of day.

This is the atmosphere that permeates this road movie, which became THE road movie par excellence. And its ascent to such an archetype is not accidental, but due to its ability to crystallize a generational sentiment, that of a youth who felt the urgency to escape bourgeois cages and wartime hypocrisies, pursuing a horizon of pure authenticity. If the literary antecedent, Kerouac's eponymous "On the Road," had celebrated the frenzy of search and the joy of discovery, "Easy Rider" is its filmic counterpart, rawer and more disillusioned, foreshadowing the end of that innocence. Its influence is palpable in every subsequent cinematic road trip, from the nihilism of "Vanishing Point" to the existential anguish of "Five Easy Pieces," demonstrating how Hopper's model redefined the genre, transforming it from a carefree epic into a modern tragedy.

Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper, in the roles of the legendary Wyatt (Captain America) and Billy, are two motorcyclists who never look back. Riding their motorcycles, shining icons of rebellion and self-affirmation, they traverse the roads of a bigoted and insular America, incapable of recognizing in these two young men two free spirits with no other purpose than to travel and be free from all constraints. Their "freedom" is a walking provocation, a living offense to the established order that sees in their long hair, in their gleaming motorcycles, and in their apparent indolence, an unacceptable threat. The film's episodic narrative, with its encounters now fleeting and friendly (the hippie commune), now openly hostile (the rednecks of the deep South), paints a merciless fresco of the social and cultural fractures that were tearing apart the United States during that period of the Vietnam War and social unrest.

Their journey will be made of places, people, songs, trips, and thoughts cast into the shadowy void of the American prairies. The soundtrack, a character in its own right, is a virtuous example of how pre-existing music can elevate the narrative. Steppenwolf's raw notes with "Born to Be Wild" become the anthem of a generation, while "The Pusher" and tracks by The Byrds and Jimi Hendrix are not mere accompaniments, but vital pulsations that mark the film's rhythm, amplifying its lyricism and intrinsic melancholy. The "trips" – the hallucinatory sequences of the New Orleans party – are not mere visual displays of a lifestyle, but desperate attempts to transcend a reality perceived as suffocating, an immersion into the psychedelic nightmare that reveals the intrinsic fragility of spiritual searching through drugs. And the "thoughts" lost in the wind, often unspoken but implicit in the silences or rarefied dialogues, carry the weight of an existential disquiet, of a search for meaning that finds answers only in the ephemeral sensation of the wind on one's face.

Their motorcycles will devour dust and stories of men, but, in a deeper sense, they themselves will be devoured. Their "being easy to ride" (easy rider) transforms into "easy to target," sacrificial victims on the altar of an America that fears what it does not understand.

Amidst a cultural revolution, Dennis Hopper embraces the perspective of the beat generation, unleashing a cry of pain, a powerful metaphor against a society concerned only with bridling its citizens with strict rules and homogenizing them through collective conformity. The film is a sharp commentary on the dichotomy between the individual pursuit of freedom and the repressive force of social conformity. Hopper's lament is not only an indictment against the violence of "middle America" but also a bitter omen of the end of the utopian dream of the Sixties, a period when hippie idealism violently clashed with the reality of a nation in convulsions. The brutality of the epilogue, as sudden as it is symbolic, seals the death of a vision and leaves the viewer with the bitter realization that, for that generation, there was no more room to run.

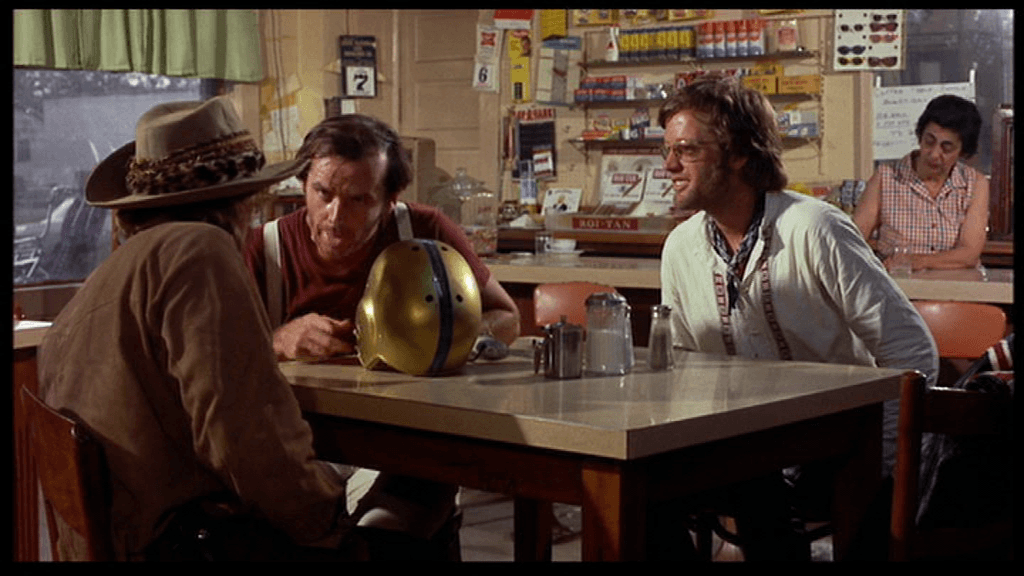

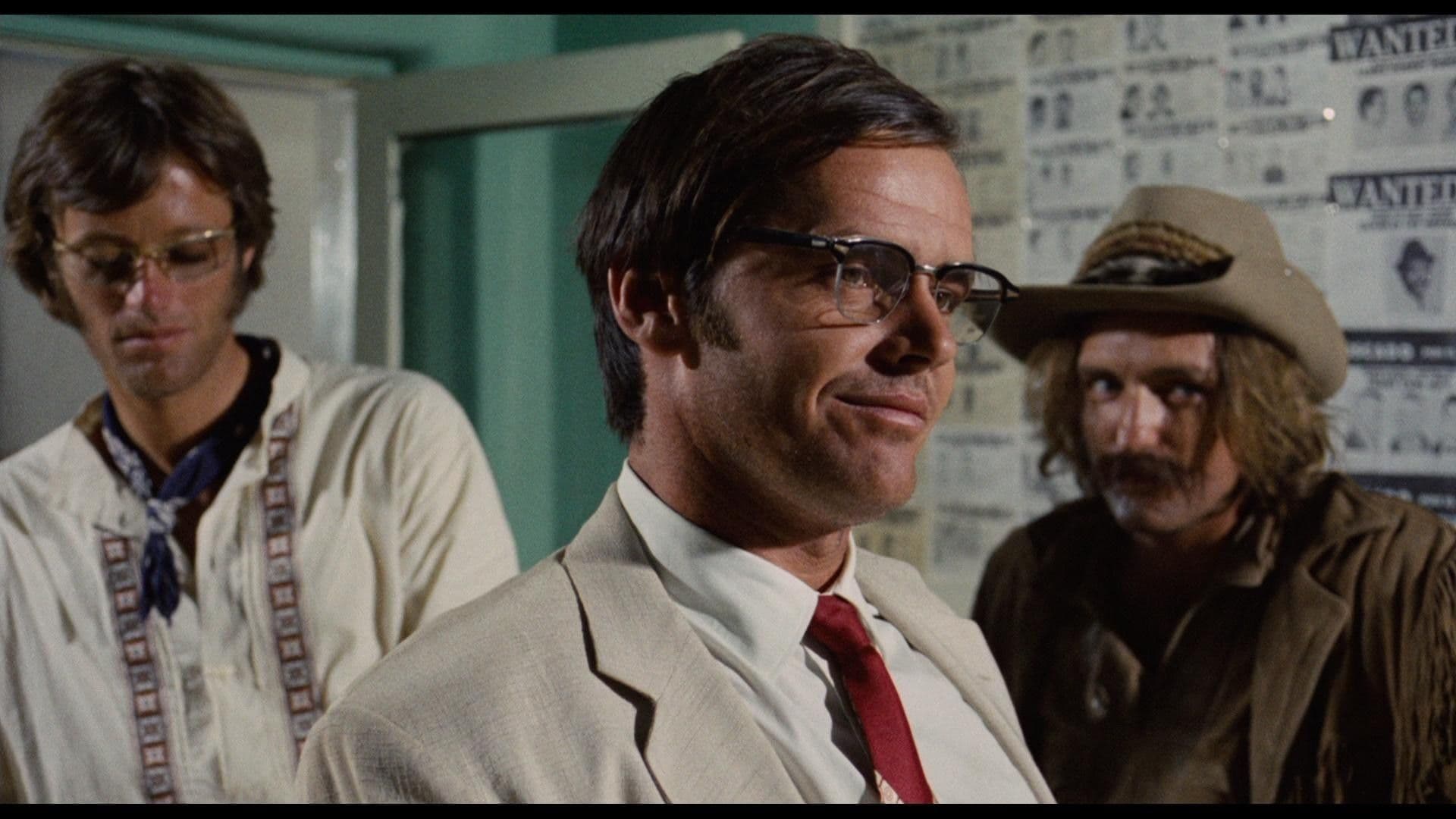

A film that made history and, among other things, marked the debut of a very young Jack Nicholson, whose portrayal of George Hanson, the alcoholic and educated lawyer, not only earned him an Oscar nomination but also became the film's moral compass. His nocturnal reflections on the meaning of freedom and the fear of the unknown that grips society ("They're scared of you... they see you as Martians") elevate the debate from a simple clash of cultures to a deeper analysis of human intolerance. His presence on screen, charged with a desperate lucidity, represents the meeting point – and then the definitive rupture – between the world of rebels and the bourgeois world, making his tragic end the symbol of the vulnerability of anyone who dares to raise their head. "Easy Rider" was not just a box office success, but an earthquake that shook the foundations of Hollywood, opening the doors to "New Hollywood" and demonstrating that low-budget, audacious, and independent films could deeply resonate with audiences, forever changing the rules of the cinematic game. Its legacy remains intact: a work that continues to question the concept of freedom and the price one is willing to pay for it, in an America that perhaps has never ceased to fear its "Martians."

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...