Embrace of the Serpent

2015

Rate this movie

Average: 5.00 / 5

(1 votes)

Director

When the journey becomes a metaphor for change, elementary catharsis, a subversion of every acquired principle, one enters a spiritual dimension where the horizon is not defined by distances traveled but by the metamorphosis of one's soul. This leitmotif, always dear to the seventh art – consider the flowing progression of Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo or the visionary psychoanalytic odyssey of Apocalypse Now, itself a spiritual child of Conrad – finds an intimate declination in Guerra’s work, almost like an initiatory rite, a descent into not only geographical but inner depths.

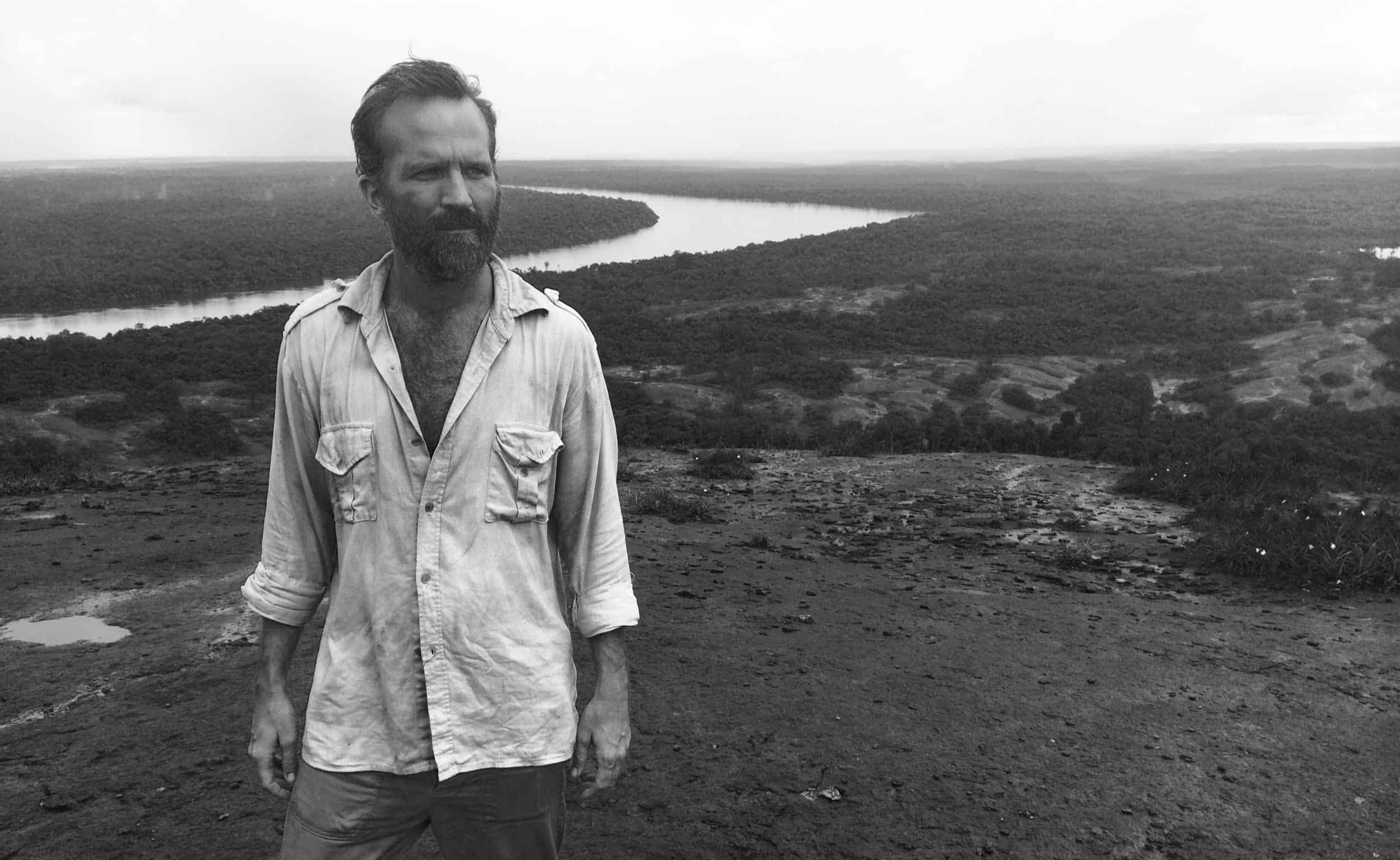

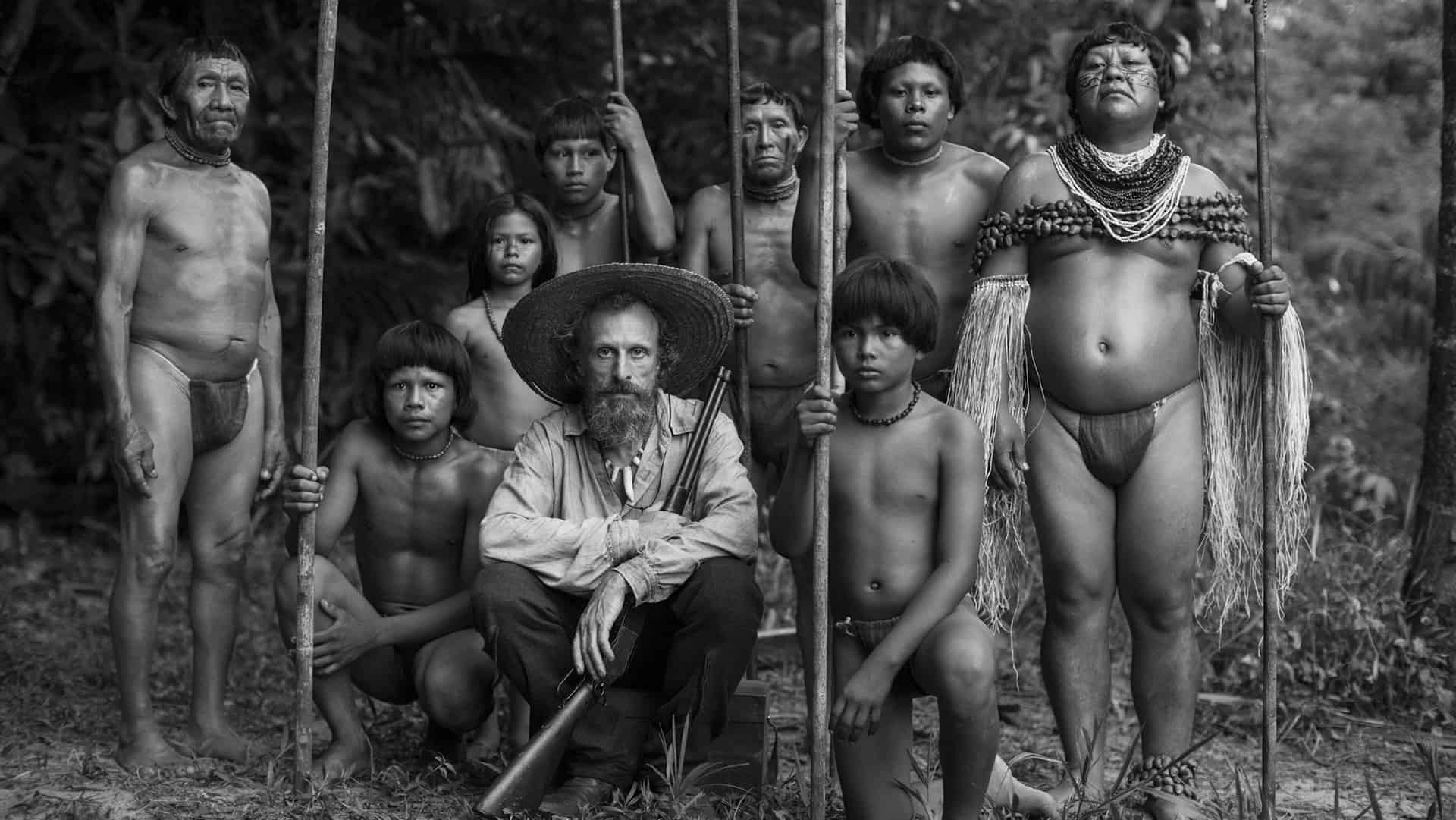

A work woven with spirituality, this film by Colombian director Ciro Guerra, in which two journeys, parallel in time and space, intertwine their events to form a single tangle where two men of science, seeking answers, lose themselves in the Amazon rainforest, merging and dissolving into the very natural elements they intended to study.

A truly evocative film, shot in stunning black and white, capable of rendering an ancestral, pantheistic, labyrinthine forest with flashes of twilight and chiaroscuro. The choice of black and white is not a mere aesthetic whim, but a bridge towards a mystical timelessness, stripping the image of every chromatic superstructure to reveal its primordial essence. It is a black and white that does not subtract but adds, imparting a dreamlike quality to the jungle, almost like an engraving from another era, reminiscent of the first photographic explorations of the nineteenth century. Every shadow, every gleam, seems to dance in a primordial ballet, amplifying the sense of an ancestral isolation, where the breath of nature is not just a backdrop, but a vital pulsation. This skillful visual construction is joined by an immersive soundscape, where the rustling of leaves, the calls of animals, the chanting of shamans are not mere diegetic elements, but the very voices of an ecosystem that whispers millennia-old secrets, swallowing Western rationalism in a vortex of altered perceptions.

The resulting perception is that of an authentic Heart of Darkness transposed onto film, a veritable incarnation of Joseph Conrad's creation that the director manages to vivify in an aesthetic and ontological dimension. It is not only the jungle that conceals horror, but the human soul itself, laid bare by the ruthlessness of an environment that reflects its darkest impulses.

And this is perhaps the most fascinating element of his film: the representation of the hallucinatory vision of a wild environment oozing with mysticism and hostility, an inextricable knot on the path of men and at the same time an irresistible attraction with its atavistic legacies.

Brazil, 1909.

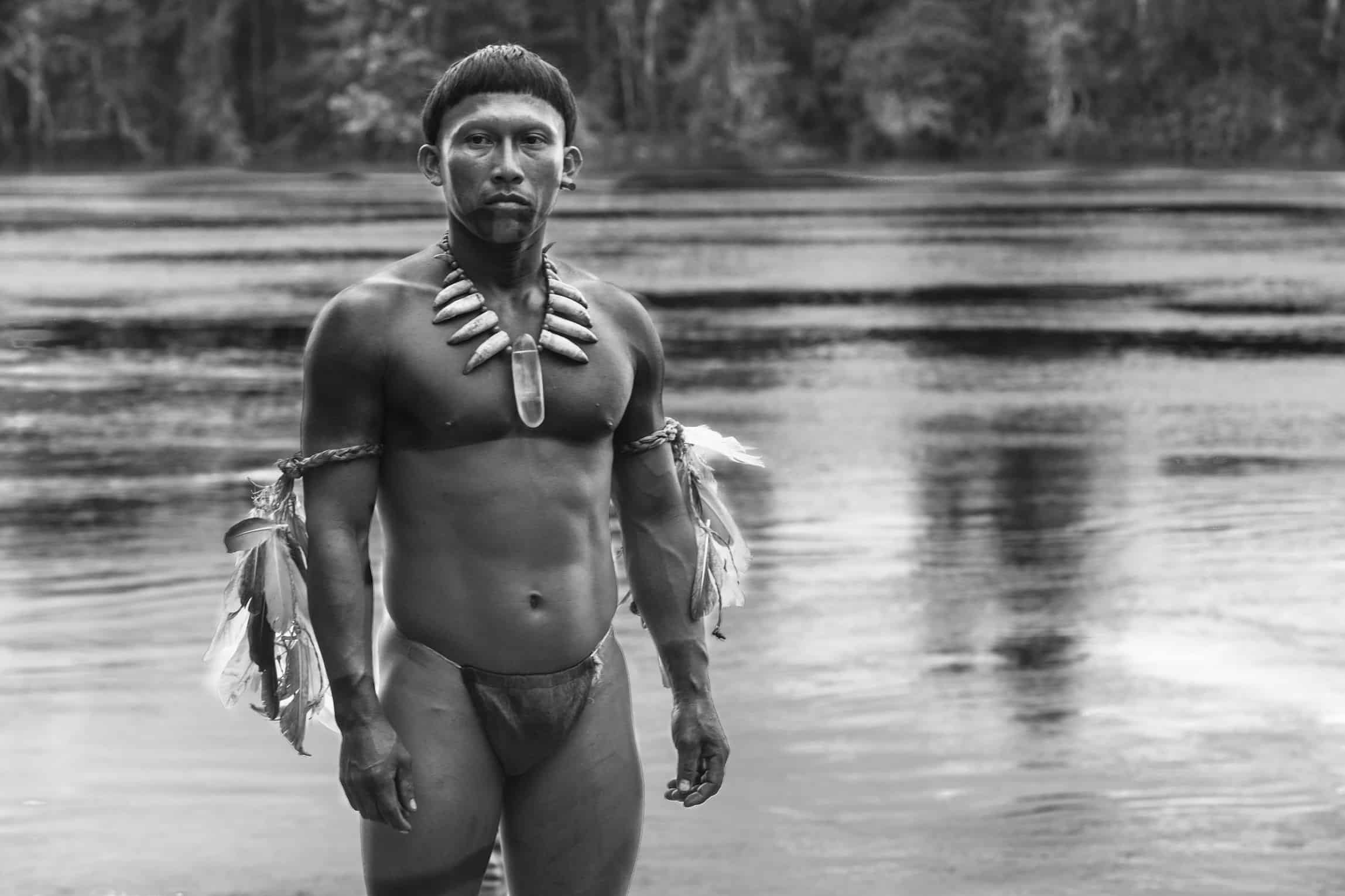

Karamakate is an Indian shaman who lives alone in a remote corner of the Amazon Rainforest after his people were exterminated by fierce rubber barons. The historical context, that of the brutal rubber boom between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, looms in the background as a silent warning. It is not a mere backdrop, but an open wound, an explicit accusation against the predatory and colonialist logic that devastated entire cultures, exterminated indigenous populations, and ruthlessly exploited natural resources. Guerra does not merely show its effects, but paints its moral genesis, the blindness of a progress that feeds on destruction. The encounter between the two white scientists and Karamakate is not just a botanical quest, but a perhaps belated attempt to mend the rift between two worlds, two radically different epistemologies, where Western knowledge, however sophisticated, often proves inadequate or destructive in the face of the systemic complexity of indigenous wisdom.

Karamakate has developed a deep resentment for white people and their brutal methods, aimed solely at serving economic interests against every elementary form of respect for life and nature.

When the Indian is approached by Manduca, a guide who asks for his help to cure Theo, a Dutch botanist and his mentor, suffering from malaria, Karamakate will initially refuse but then accept to treat the man. Once recovered, the scientist convinces Karamakate to accompany him to the place where a plant with miraculous powers called Yacruna grows. The shaman agrees on condition that Manduca and Theo follow his precepts during the journey. The Yacruna, more than a simple plant, becomes a McGuffin steeped in sacredness, the focal point of a quest that is simultaneously scientific, spiritual, and one of reconciliation.

Parallel to this, another journey of Karamakate begins, placed chronologically forty years later, with another scientist, an American ethnographer, also searching for the Yacruna. It will be an opportunity for the old Indian to confront the demons hidden in the folds of his memory, embarking on a new journey that will forever change his soul.

Based on real events that Guerra reinterpreted through the filter of his sensibility, the film is inspired by the journeys undertaken in the Amazon Rainforest by scientists Theodor Koch-Grunberg and Richard Evans Schultes. Guerra's work lingers long in the memory by virtue of an adventurous aspect that masterfully blends with the speculative spiritual dimension.

A paradigmatic and memorable scene is Karamakate's explanation of the concept of Chullachaqui to Evan: the American biologist is leafing through some photographs he has taken and shows one of them to Karamakate; it is a photograph depicting Karamakate himself. The Indian addresses the portrait, calling it a Chullachaqui. For some Amazonian Indian tribes, the Chullachaqui is an empty double of ourselves, emptied of all essence, a ghost in our likeness that wanders the world. Cultures light-years apart, such as the Native Americans, the Amazonian Indians, or the Maasai of central Africa, refuse to be photographed so as not to generate a Replica of themselves, deprived of all substance but free to leave.

The Chullachaqui, the Doppelgänger, the digital Avatar of our online lives: this vacant Ghost has passed through centuries of history, cultures, traditions yet has not lost its (non-)meaning, its silent horror. In this dizzying array of meanings, the Chullachaqui transcends simple folklore to become a powerful metaphor for identity in the era of technical reproducibility. Karamakate, holding his own photographic effigy, is not merely an Indian who rejects the image, but a symbol of resistance against the commodification of being, against the reduction of a person to data, to a disembodied 'copy'. It is a silent cry against the process of desubstantialization that modernity, with its technologies and classificatory logics, imposes on the individual. Is not the digital age, with its virtual profiles and fragmented identities, the quintessence of the Chullachaqui? A bodiless presence, a shadow wandering the net, emptied of the materiality and rootedness that Karamakate defends with every fiber of his being. Guerra's film, while drawing from a remote past, thus becomes prophetically contemporary, questioning the frontiers of perception, memory, and representation in a world where the line between authentic and reproduced becomes increasingly blurred, leaving the Chullachaqui, our ghost double, to embody that horror lost in time yet terribly present.

Main Actors

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...