Fahrenheit 451

1966

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

A controversial film, opposed by a part of the critics who did not forgive Truffaut for betraying his distinctly European flair to dedicate himself to an overly Americanized project (starting with Ray Bradbury's novel it is based on, a science fiction book at that). An accusation, that of having pandered to a genre and a market usually far from the authorial idiosyncrasies of the Nouvelle Vague, which today, decades later, appears not only myopic but profoundly unjust. Truffaut, the standard-bearer of a cinematography devoted to introspection and expressive freedom, was not betraying anything; rather, he was expanding the boundaries of his own language, demonstrating how even a science fiction archetype could be imbued with an exquisitely authorial sensibility, transforming the genre into a vehicle for philosophical and humanistic reflection.

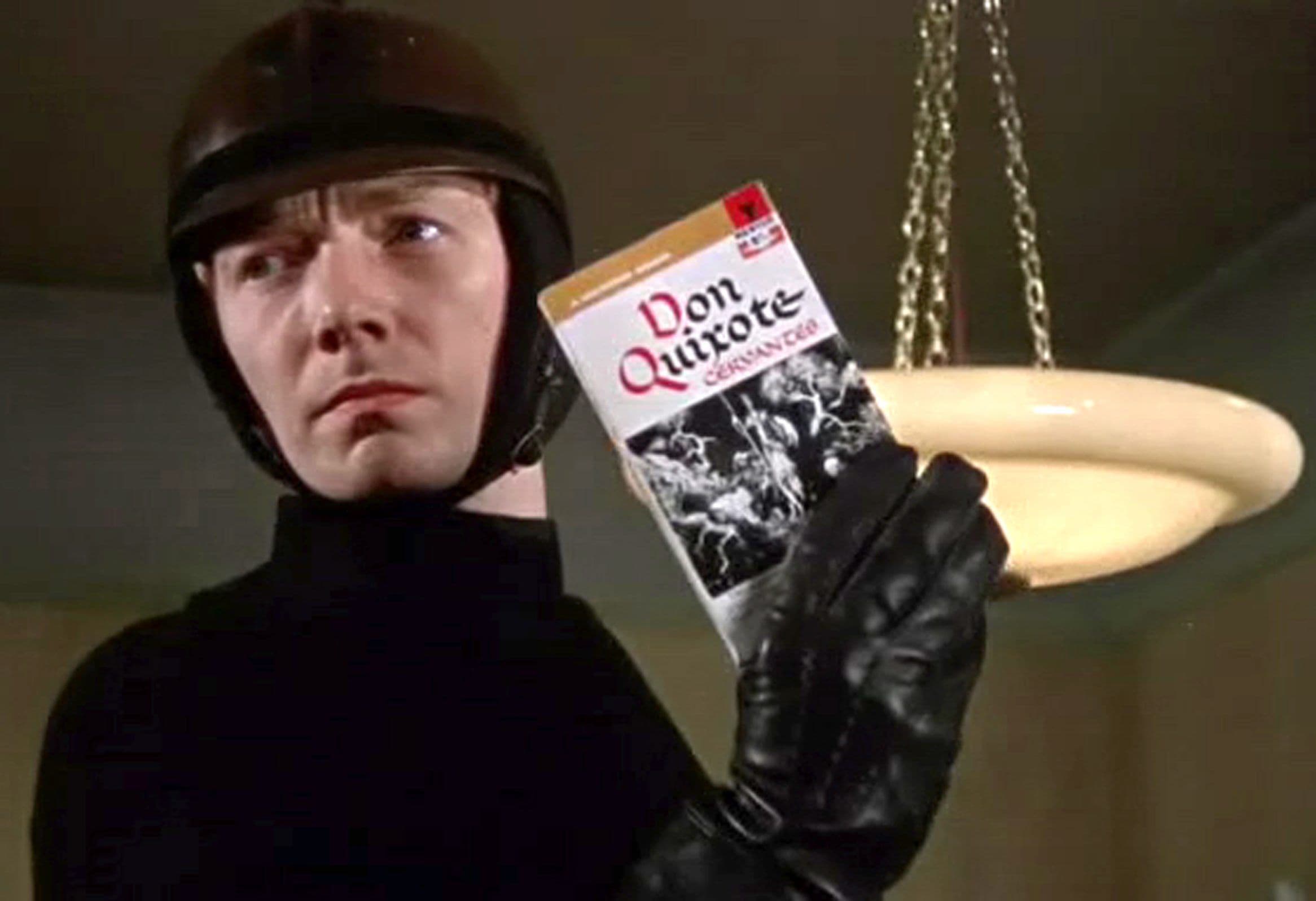

In reality, a film of great stature, where the French director's love for the written word enhances the narrative register and directorial dimension, creating a captivating and moving story. The choice to film in English, despite numerous linguistic and production difficulties, such as those with a restless Oskar Werner or an almost absent Julie Christie (who plays a dual role, Clarisse and Linda, Montag's wife, a device to highlight the contrast between the desire for knowledge and obtuse conformity), testifies to his determination to reach a wider audience with a universal message. His love for books, tangible in his life as a cinephile and critic for "Cahiers du Cinéma," finds a visual transposition of rare power here. Every shot of the forbidden volumes, be they literary masterpieces or simple magazines, is permeated with an almost sacred veneration, transforming the printed text into a fetish of freedom and memory. It is no coincidence that Truffaut, always attentive to the poetic dimension of storytelling, imbues the film with a kind of visual lyricism, contrasting the sterility of the dystopian world with the intrinsic richness of ideas imprisoned within the pages.

The narrative takes shape in an unspecified future, where a state department, the so-called firemen, is tasked with burning books. The totalitarian regime, whose genesis is ambiguously left suspended, is based on a subtle and pervasive intellectual coercion, not so much on brute force as on the gradual atrophy of critical thought, on mass distraction provided by an omnipresent and anaesthetizing television screen, a disturbing premonition of today's information society. In this desolate context, one of the firemen, Montag, embodied by an Oskar Werner perfectly balanced between obtuseness and dawning awareness, will meet Clarisse, played with ethereal grace by Julie Christie, a woman who instills in him a love for reading. It is not a passionate love, but rather an intellectual spark, an awakening of dormant curiosity, an invitation to look beyond society's polished surface. Clarisse is the archetypal figure of the "involuntary dissident," the voice that breaks the silence of conformity, and her gentle but resolute approach prompts Montag to embark on an inner journey of rupture.

He will begin his gradual evolution towards the awareness that the written word is the most sacred and pure thing man can preserve. Not just pure information, but a vehicle for empathy, historical memory, diversity of thought, and, ultimately, human identity. It is a tortuous and dangerous path, marked by furtive nocturnal readings that reveal an unknown universe of ideas, emotions, and contradictions.

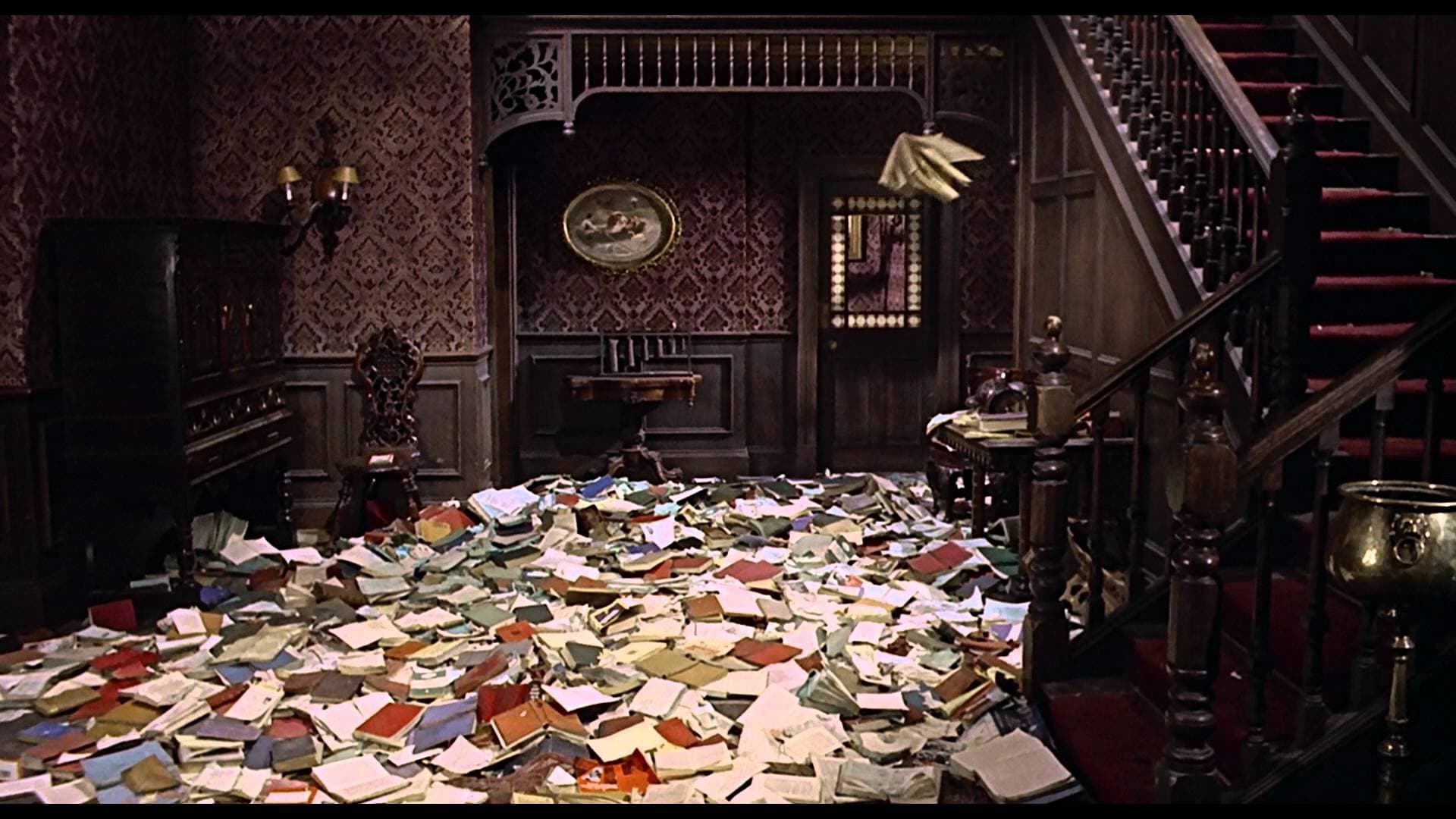

One scene above all: the discovery of the secret library where Captain Beatty, after calling Montag to witness, launches his philippic against books. Truffaut plays with the two men amidst all those books, alternating close-ups of covers and spines with close-ups of the Captain's diabolical expressions as he unleashes his barbs against the written word. This confrontation is not just a verbal duel, but a genuine battle for Montag's soul. Captain Beatty, masterfully played by Cyril Cusack, is not a mere brutal henchman; he is a failed intellectual, a man who has read books and understood their subversive power, choosing to serve the cause of their destruction. His oratory is a perverse sophism, an indictment against the complexity, ambiguity, and suffering that knowledge brings, preferring the easy happiness of ignorance. The close-ups of the covers – classic texts, novels, encyclopedias – are not just objects, but symbols of entire worlds about to be annihilated, while the Captain's face twists in a mixture of fanaticism and disillusionment, revealing the tragedy of a soul that has chosen the destruction of thought. It is a sequence that, due to its dramatic intensity and visual intelligence, ranks among the pinnacles of dystopian cinema, ideally dialoguing with the most distressing sequences of a "1984" or a "Brave New World" filmed with equal psychological acumen.

The use of the camera is excellent, always naturally documenting the succession of events without indulging in frivolous mannerisms. Nestor Almendros's cinematography, a loyal collaborator of Truffaut, decisively contributes to creating a suspended, almost dreamlike atmosphere, while maintaining a documentary rigor. The warm, almost burned colors of the fire scenes contrast with the colder and more neutral palette of the interiors, visually emphasizing the conflict between destruction and the search for truth. There is no stylistic ostentation, but rather a sober elegance functional to the narration, which allows the viewer to immerse themselves unfiltered into the anguish of a world where knowledge is a crime and memory a burden. The final climax, with the "book people" who preserve literature within themselves, is a moving testament to Truffaut's unwavering faith in the power of culture and the indomitable resilience of the human spirit, a silent but powerful ode to humanity's ability to resist oblivion and to re-establish, even from the ashes, its heritage of ideas and stories. "Fahrenheit 451" remains a sharp and disarming warning, whose relevance is renewed, bitterly, with every societal slide towards superficiality and the negation of complexity.

Genres

Country

Gallery

Comments

Loading comments...