Chimes at Midnight

1965

Rate this movie

Average: 0.00 / 5

(0 votes)

Director

Welles pays his debt to Shakespeare by creating a work of poignant lyricism through a risky "collatio" operation performed on several Shakespearean plays: Henry IV, Henry V, The Merry Wives of Windsor, Richard II. It is perhaps no coincidence that Welles's eclecticism, his inexhaustible curiosity for narrative forms, and his almost titanic audacity in manipulating the raw material, found in the Bard the perfect canvas for his genius. This "collatio" is not mere collage, but a true alchemical distillation, a hermeneutic operation aiming to extract a new and more intense tragic truth from the Shakespearean corpus, focusing on the fate of Sir John Falstaff, an archetype of freedom and authenticity, destined to succumb under the weight of raison d'état and the ruthless ascent to power. It is an act of visionary philology, creating a superior dramatic coherence, a narrative arc for the character that Shakespeare himself had disseminated, but never with such concentrated and devastating intensity.

It should be added that the film was produced with great scarcity of means, a condition of perennial exile and financial struggle that had plagued much of Welles's post-Hollywood career. Every shot, every stylistic choice in Falstaff (also known as Chimes at Midnight) is imbued with the stubbornness and ingenuity of one who operates on the margins, transforming necessity into virtue. The sets are often sparse or evoked with a few essential details, real locations skillfully exploited to suggest eras and atmospheres, costumes recycled or improvised. This economy of means, far from limiting the vision, enhances it, forcing Welles into a formal rigor and stylization that lend the work an almost dreamlike quality, a pictorial abstraction evoking the chiaroscuro of Flemish painting or Goya's etchings, confirming how genius can flourish even in the most extreme aridity, shaping nothingness into vibrant substance.

Despite all this, a masterpiece forged from nothing is the result, born from the genius of a filmmaker like truly few others. Welles's mastery lies not only in his authorial vision but in his ability to translate the text into pure cinematic language: the deep focus that creates visual labyrinths, the audacious camera angles that deform and magnify, the syncopated and almost expressionistic editing that culminates in the legendary Battle of Shrewsbury sequence, where the chaos and brutality of the conflict are rendered with a feverish, almost abstract rhythm, a macabre dance that transcends mere historical representation to become a meditation on the futility of violence. A visual tour de force whose dynamic agitation contrasts with moments of quiet, poignant contemplation.

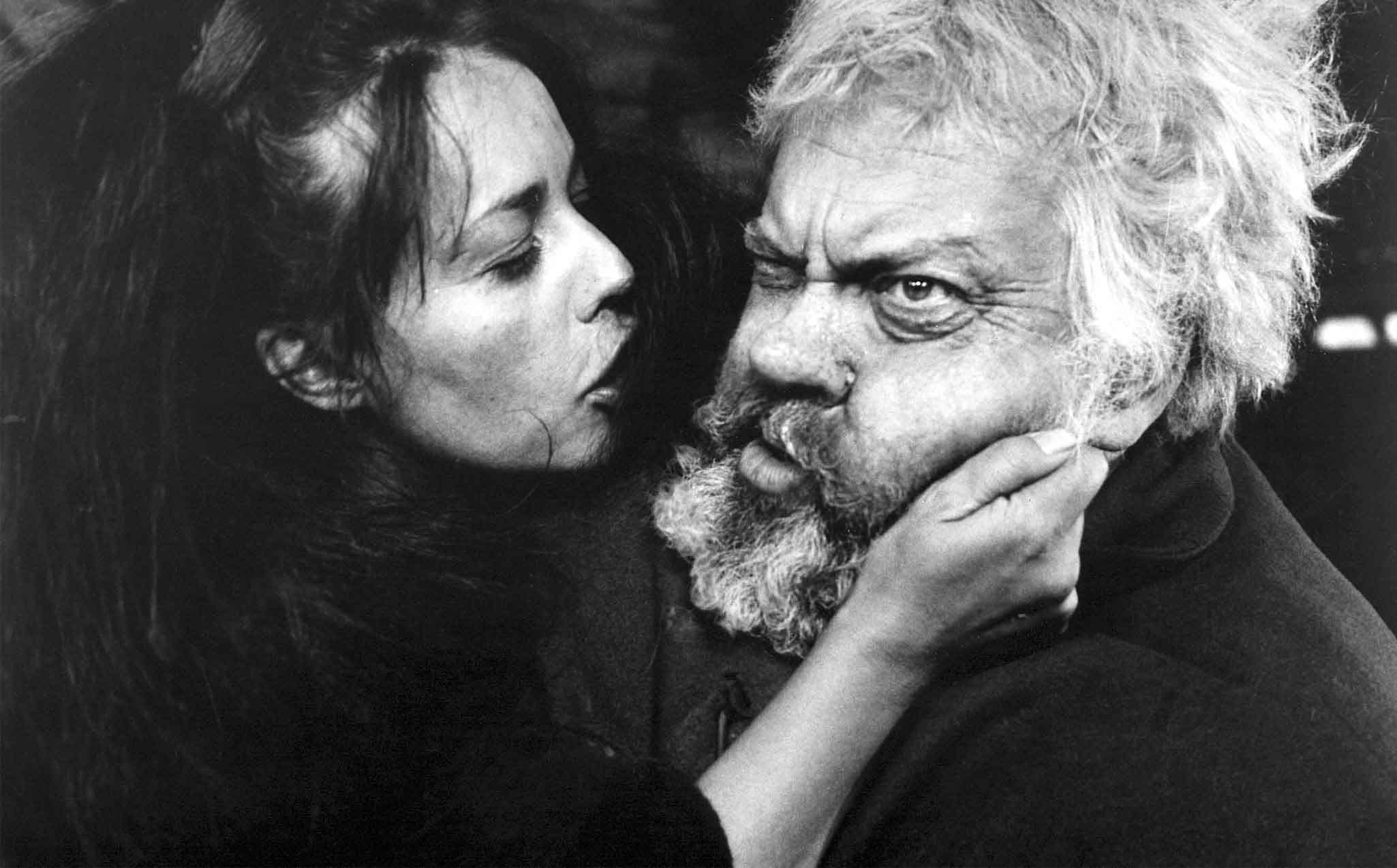

Welles portrays Falstaff, the man who is disowned by his childhood friend, Henry IV, as soon as the latter ascends to the throne. It is a monumental performance, an embodiment that transcends mere acting to reach an almost mythological dimension. Welles does not merely don the corpulent knight's attire, but inhabits him with his own complex biography as a misunderstood genius, a titanic yet vulnerable figure, perpetually struggling with the contingencies of power. His Falstaff is a sublime amalgam of buffoonery and wisdom, of genial epicureanism and ill-concealed disillusionment, a putative father and a carousing companion whose unrestrained vitality is destined to extinguish under the weight of a reality that no longer tolerates his anarchic freedom. His cavernous voice, his heavy gaze steeped in bitter irony, his imposing physicality that moves with unexpected grace or desolate slowness, construct a character of immeasurable pathos, a symbol of a vanishing world.

Falstaff's melancholic gaze encompasses an entire life and helplessly witnesses the disintegration of a network of affections and memories suddenly fallen into oblivion. This is the true tragedy of the film: not physical death, but the death of friendship, the erasure of a shared past, the betrayal of the purest ideals in the name of raison d'état. Hal's abandonment is the mortal blow, a gesture of cynical political pragmatism that condemns Falstaff to a desolate solitude, to an inner exile. Welles captures the deafening silence of that rejection, the weight of trampled dignity, the melancholy of a lost golden age. The film thus transforms into an elegiac lament not only for Falstaff but for an entire era, for the innocence that youth is forced to sacrifice on the altar of power, for the human bonds that are torn apart by the cold logic of government.

A film that carves out the contours of the decadent hero: in total abandonment, the poetics of dissolution appear as a compelling hyperuranium, impossible to resist. Falstaff is not merely a character who declines, but the very embodiment of decadence, understood not as a moral failing but as an inevitable process of an era's, of an ethic's, consumption. His figure stands out as a warning, a sculpture of melancholy that foreshadows the end of a chivalric world, replaced by the cold rationality of modern politics. The "poetics of dissolution" manifest not only in the protagonist's destiny but in Welles's aesthetic itself: the often-fragmented shots, the silhouettes enveloped in shadow, faces illuminated by a Caravaggesque light that reveals their weariness and resignation, the music that mournfully accompanies the twilight. The hyperuranium here is not a Platonic realm of perfect ideas, but a metaphorical kingdom where pain and loss assume an ideal form, a tragic beauty to which the human spirit, in its fragility, can only surrender, recognizing its own inescapable fate. It is the dissolution of a dream, the end of an anarchic vitality crushed by conventions and ambitions, a theme that resonates with Welles's personal artistic odyssey, a genius constantly at odds with the establishment.

Welles duplicates himself: sublime performer and magical puppeteer pulling the strings of the characters on stage. His direction is an act of knowing manipulation, a play of shadows and lights that reveals and conceals, an orchestrated visual symphony that translates the complexity of the Shakespearean text into a dense and layered cinematic language. Every camera movement, every editing choice, every use of sound (often distorted, distant, like a vanished memory) is aimed at evoking the intense dramatic quality of the narrative and the profound melancholy that permeates every frame. Welles is at once the object and the subject of his own vision, a demiurge who shapes his cinematic alter ego, a Falstaff who is also somewhat Welles himself, titanic and tragic, a monument to the greatness and solitude of genius.

Powerful and visionary, Falstaff is not only a Shakespearean adaptation but a profoundly personal work, an artistic testament reflecting the obsessions of an auteur out of time, a swan song for an idea of epic and profoundly human cinema. It is a film that, in its moving lyricism and ruthless analysis of power and betrayed friendship, continues to resonate with a timeless truth, solidifying Welles's position as one of the greatest and most tragic visionaries of the seventh art.

Genres

Countries

Gallery

Featured Videos

Official Trailer

Comments

Loading comments...